THE CLASH OF TWO EMPIRES ROME VS GREECE

In the Roman epic of Virgil, the Aeneid, Queen Dido, the Greek name for Queen Elissa, is first introduced as an extremely respected character. In just seven years, since their exodus from Tyre, the Carthaginians have rebuilt a successful kingdom under her rule. Her subjects adore her and present her with a festival of praise. Her character is perceived by Virgil as even more noble when she offers asylum to Aeneas and his men, who have recently escaped from Troy. A spirit in the form of the messenger god, Mercury, sent by Jupiter, reminds Aeneas that his mission is not to stay in Carthage with his new-found love, Dido, but to sail to Italy to found Rome. Virgil ends his legend of Dido with the story that, when Aeneas tells Dido, her heart broken, she orders a pyre to be built where she falls upon Aeneas' sword. As she lay dying, she predicted eternal strife between Aeneas' people and her own: "rise up from my bones, avenging spirit" (4.625, trans. Fitzgerald) she says, an invocation ofHannibal. The details of Virgil's story do not, however form part of the original legend and are significant mainly as an indication of Rome's attitude towards the city she had destroyed, exemplified by Cato the Elder's much-repeated utterance, "delenda est Carthaga", Carthage must be destroyed.[9]

[edit]Carthaginian Republic

Main article: Carthaginian Republic

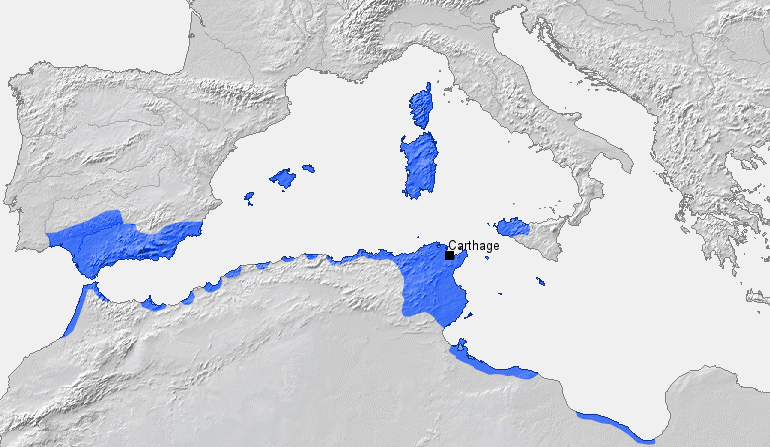

Carthaginian held territory in the early 3rd century BC

The Carthaginian Republic was one of the longest-lived and largest states in the ancient Mediterranean. Reports relay several wars with Syracuse and finally, Rome, which eventually resulted in the defeat and destruction of Carthage in the third Punic war. The Carthaginians were Semitic Phoeniciansettlers originating in the Mediterranean coast of the Near East. They spokeCanaanite and followed a predominantly Canaanite religion.

[edit]Army

Main article: Military of ancient Carthage

According to Polybius, Carthage relied heavily, though not exclusively, on foreign mercenaries,[10] especially in overseas warfare. The core of its army was from its own territory in north Africa (ethnic Libyans and Numidians (modern northernAlgeria), as well as "Liby-Phoenicians" — i.e. Phoeniciansproper). These troops were supported by mercenaries from different ethnic groups and geographic locations across the Mediterranean who fought in their own national units; Celtic, Balearic, andIberian troops were especially common. Later, after the Barcid conquest of Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal),Iberians came to form an even greater part of the Carthaginian forces. Carthage seems to have fielded a formidable cavalry force, especially in its North African homeland; a significant part of it was composed of Numidian contingents of light cavalry. Other mounted troops included the now extinct North African elephants, trained for war, which, among other uses, were commonly used for frontal assaults or as anti-cavalry protection. An army could field up to several hundred of these animals, but on most reported occasions fewer than a hundred were deployed. The riders of these elephants were armed with a spike and hammer to kill the elephants in case they charged toward their own army.

[edit]Navy

Roman trireme mosaic from Carthage,Bardo Museum, Tunis

The navy of Carthage was one of the largest in the Mediterranean, using serial production to maintain high numbers at moderate cost. The sailors andmarines of the Carthaginian navy were predominantly recruited from the Phoenician citizenry, unlike the multi-ethnic allied and mercenary troops of the Carthaginian armies. The navy offered a stable profession and financial security for its sailors. This helped to contribute to the city's political stability, since the unemployed, debt ridden poor in other cities were frequently inclined to support revolutionary leaders in the hope of improving their own lot.[11]The reputation of her skilled sailors implies that there was in peacetime a training of oarsmen and coxswains, giving their navy a cutting edge in naval matters.

The trade of Carthaginian merchantmen was by land across the Sahara and especially by sea throughout the Mediterraneanand far into the Atlantic to the tin-rich islands of Britain and also to North West Africa. There is evidence that at least one Punic expedition under Hanno sailed along the West African coast to regions south of the Tropic of Cancer, describing how the sun was in the north at noon.[citation needed]

Polybius wrote in the sixth book of his History that the Carthaginians were "more exercised in maritime affairs than any other people."[12] Their navy included some 300 to 350 warships. The Romans, who had little experience in naval warfare prior to the First Punic War, managed to finally defeat Carthage with a combination of reverse engineering captured Carthaginian ships, recruitment of experienced Greek sailors from the ranks of its conquered cities, the unorthodox corvus device, and their superior numbers in marines and rowers. In the Third Punic War Polybius describes a tactical innovation of the Carthaginians, augmenting their few triremes with small vessels that carried hooks (to attack the oars) and fire (to attack the hulls). With this new combination, they were able to stand their ground against the numerically superior Roman for a whole day.

[edit]Fall

Ruins of Carthage

The fall of Carthage came at the end of the Third Punic War in 146 BC at the Battle of Carthage.[13] Despite initial devastating Roman naval losses and Rome's recovery from the brink of defeat after the terror of a 15-year occupation of much of Italy byHannibal, the end of the series of wars resulted in the end of Carthaginian power and the complete destruction of the city byScipio Aemilianus. The Romans pulled the Phoenician warships out into the harbour and burned them before the city, and went from house to house, capturing, raping and enslaving the people. Fifty thousand Carthaginians were sold into slavery.[14]The city was set ablaze, and razed to the ground, leaving only ruins and rubble. After the fall of Carthage, Rome annexed the majority of the Carthaginian colonies, including other North African locations such as Volubilis, Lixus, Chellah, and Mogador.[15] The legend that the city was sown with salt is not mentioned by the ancient sources; R.T. Ridley suggested that the story originated from 1930 in section of the Cambridge Ancient History written by B Hallward whose influence might be an account of Abimelech's salting of Shechem in Judges 9:45.[16][17] Warmington admitted his fault in repeating Hallward's error but mentions an example of the story that goes back to 1299 when Bonaface VIII destroyed Palestrina.[18]

[edit]City of survivors

[edit]Byrsa

Main article: Byrsa

Punic ruins in Byrsa

On top of Byrsa hill, the location of the Roman Forum, a residential area from the last century of existence (early 2nd century) of the Punic city was excavated by the French archaeologist Serge Lancel. The neighborhood, with its houses, shops and private spaces, is significant for what it reveals about daily life there over twenty-one hundred years ago. .[19]

The habitat is typical, even stereotypical. The street was often used as a storefront; cistern tanks were installed in basements to collect water for domestic use, and a long corridor on the right side of each residence led to a courtyard containing a sump, around which various other elements may be found. In some places the ground is covered with mosaics called punica pavement, sometimes using a characteristic red mortar.

The remains have been preserved under embankments, the substructures of the later Roman forum, whose foundation piles dot the district. The housing blocks are separated by a grid of straight streets approximately six metres wide, with a roadway consisting of clay; there are in situ stairs to compensate for the slope of the hill. Construction of this type presupposes organization and political will, and has inspired the name of the neighborhood, "Hannibal district", referring to the legendary Punic general or Suffete (consul) at the beginning of the 2nd century BC.

[edit]Other alternatives

Roman Carthage

When Carthage fell, its nearby rival Utica, a Roman ally, was made capital of the region and replaced Carthage as the leading center of Punic trade and leadership. It had the advantageous position of being situated on the Lake of Tunis and the outlet of the Majardah River, Tunisia's only river that flowed all year long. However, grain cultivation in the Tunisian mountains caused large amounts of silt to erode into the river. This silt accumulated in the harbor until it became useless, and Rome was forced to rebuild Carthage.

By 122 BC Gaius Gracchus founded a short-lived colony, called Colonia Iunonia, after the Latin name for the punic goddessTanit, Iuno caelestis. The purpose was to obtain arable lands for impoverished farmers. The Senate abolished the colony some time later, in order to undermine Gracchus' power.

After this ill-fated attempt a new city of Carthage was built on the same land by Julius Caesar in 49-44 BC period, and by the 1st century A.D. it had grown to be the second largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire, with a peak population of 500,000[citation needed]. It was the center of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the Empire.

Carthage also became a centre of early Christianity. In the first of a string of rather poorly-reported councils at Carthage a few years later, no fewer than 70 bishops attended. Tertullian later broke with the mainstream that was represented more and more in the west by the bishop of Rome, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, whichAugustine of Hippo spent much time and parchment arguing against. In 397 AD at theCouncil at Carthage, the biblical canon for the western Church was confirmed.

[edit]Vandals

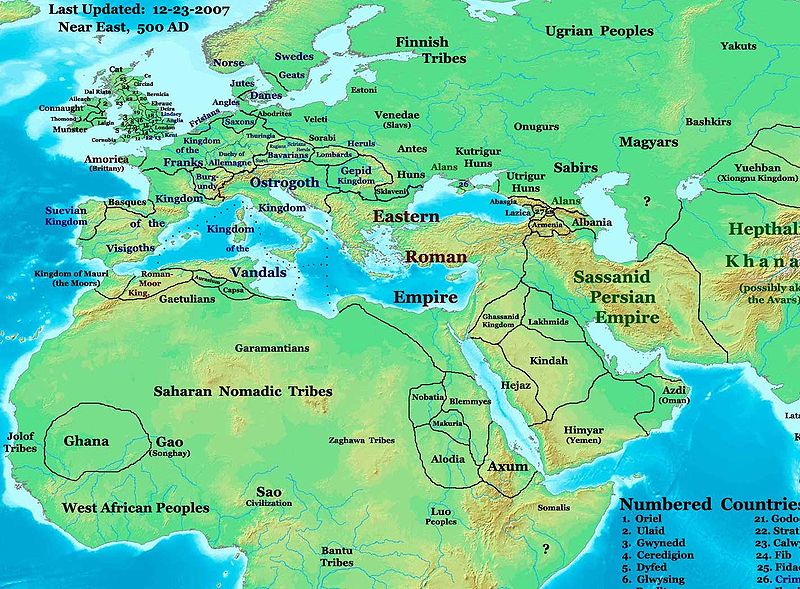

Vandal Empire in 500 AD, centered in Carthage.

The political fallout from the deep disaffection of African Christians is supposedly a crucial factor in the ease with which Carthage and the other centres were captured in the 5th century by Gaiseric, king of the Vandals, who defeated the Romangeneral Bonifacius and made the city his capital. Gaiseric was considered a heretic too, an Arian, and though Arians commonly despised orthodox Catholic Christians, a mere promise of toleration might have caused the city's population to accept him. After a failed attempt to recapture the city in the 5th century, the Eastern Roman empire finally subdued the Vandals in theVandalic War 533-534.

Thereafter the city became the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa, which during the emperor Maurice's reign, was made into an Exarchate, as was Ravenna in Italy. These two exarchates were the western bulwarks of the Roman empire, all that remained of its power in the west. In the early 7th century it was the exarch of Carthage who overthrew emperor Phocas.

[edit]Islamic conquests

The Roman Exarchate of Africa was not able to withstand the Muslim conquerors of the 7th century. Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik in 686 AD sent a force led by Zuhayr ibn Qais who won a battle over Romans and Berbers led by Kusaila, on theQairawan plain; but could not follow that up. In 695 ADHasan ibn al-Nu'man captured Carthage and advanced into the Atlas Mountains. An imperial fleet arrived and retook Carthage, but in 698 AD Hasan ibn al-Nu'man returned and defeated emperorTiberios III at the Battle of Carthage. Roman imperial forces withdrew from all Africa except Ceuta. Roman Carthage was destroyed and was replaced by Tunis as the major regional centre. The destruction of the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to the influence there of the eastern Roman empire.

[edit]Modern times

In the mid-19th century Nathan Davis and other European archaeologists were given permission to excavate the ancient city.

Carthage remains a popular tourist attraction and residential suburb of Tunis. The Tunisian presidential palace is located in the city.[20]

In February 1985, Ugo Vetere, the mayor of Rome, and Chedly Klibi, the mayor of Carthage, signed a symbolic treaty "officially" ending the conflict between their cities, which had been supposedly extended by the lack of a peace treaty for more than 2,100 years

Detail of frieze showing the equipment of a soldier in the manipular Roman legion (left). Note mail armour, oval shield and helmet with plume (probably horsehair). The soldier at centre is an officer (bronze cuirass, mantle), prob. a tribunus militum.[17] From an altar built by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, consul in 122 BC. Musée du Louvre, Paris

Rome vs Greece: a little-known clash of empires

The fate of Greek city states which had aided the Roman invasion was most ironic

[Editor’s note: Last week we were the recipients of one of the most laughably ludicrous assertions possible – that the glories of Ancient Greece and Rome were nothing more than a fiction conjured up by Irish monks. So when I saw this article, ironically the work of an Irishman, I could not resist reproducing it in order to redress the balance that had been upset by that ludicrous assertion that Ancient Rome and Greece were a fiction. This is real history, not the half-baked ramblings we have sadly seen from others. ]

__________

The Irish Times

Ancient Greece. Ancient Rome. These words conjure up powerful images: the Olympic Games and the siege of Troy for the former; emperors, legions and gladiator fights for the latter. Two civilisations that impacted massively on world history, their effects are still evident today in language and legal structures, in sport, medicine and philosophy. It’s odd then that the clash between the two powers is so little-known today. Researching the period, I was amazed that no one had written, recently at least, about one of the most seismic moments in European history.

Clash of Empires is the result, and the first in a two-part series.

Let us set the stage. Before the outbreak of the second Punic war in 218 BC (the one with Hannibal and the passage of the Alps with elephants!), the Roman Republic controlled perhaps three-quarters of the Italian peninsula. Its only external territories were the islands of Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia. There were four other powers in the Mediterranean world, two of which were a great deal larger than Rome. In order of size these were the Seleucid Empire, which extended from modern-day Turkey to India, Carthage on the North African coast, which also controlled most of the Iberian peninsula, Ptolemaic Egypt, ruled by Greek-speaking descendants of one of Alexander’s generals, and Macedon, which dominated much of Greece.

By 168 BC, 50 years later, just two powers remained: Rome and a tottering Egypt. The others had been defeated by the military bulldozers that were the legions. Rome had changed identity forever. No longer the combative newcomer of the Mediterranean world, it was now a confident, brash superpower. The first paving stones of the road to empire had been well and truly laid.

The history of Rome and Macedon is a tangled one; to explain it in depth goes beyond the remit of this article. The two powers actually fought three wars, from 217 to 205 BC, 200 to 197 BC and 171 to 168 BC; the second was of most consequence. A short but brutal affair, it was also the conflict that saw Rome’s authority stamped on Greece, and is the one upon which we will focus.

The ruler of Macedon at the time of both the first and second conflicts was the mercurial and unpredictable King Philip V. Scion of a different family to Alexander the Great (whose line had been wiped out after his death), Philip was capable of individual acts of military brilliance and colossally rash decisions. Cursed by the fact that most city states in Greece loathed Macedon, as they had since Alexander’s time, he spent his reign dealing with political machinations against him, invasions from neighbouring territories and open war with many of his neighbours.

Philip seemed to live his life by the ancient Greek saying that a king who lived in peace was no king at all.

On all points of the compass then, Macedon had enemies, open, hidden or in the making, and when Philip wasn’t dealing with these problems, he was invading or fighting with other kingdoms and territories. Illyria and Epirus (modern-day Croatia/Montenegro/Albania), Thrace (Bulgaria), the Hellespont (the Straits of Bosphorus) and the western coastline and islands of Asia Minor (Turkey) all suffered his attacks on more than one occasion. Philip seemed to live his life by the ancient Greek saying that a king who lived in peace was no king at all. It’s hard not to draw the conclusion that he had aspirations of emulating the feats of his illustrious predecessor Alexander. Sadly for Philip, he never quite succeeded in that regard.

By the autumn of 202 BC, the 17-year war between Rome and Carthage was drawing to a close. The final act took place at Zama, not far from the city of Carthage; the battle resulted in a decisive defeat for Hannibal’s army. After a conflict that had lasted a generation, seen huge swathes of Italy go over to the enemy, and cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of its citizens, one might assume that the Roman Republic would have lost its appetite for war by this point. Not so. Less than two years after Zama, embassies sent by Philip’s enemies in Asia Minor pleaded for help against his attacks on their territories. Conjuring the idea of a possible Macedonian invasion of Italy, these emissaries won over the Senate. There was some resistance from the Centuriate, the people’s assembly, but the vote for war was carried in the summer of 200 BC.

Rome didn’t hang about, dispatching an army to Apollonia in modern-day Albania. Autumn had arrived before the legions could march inland; although they succeeded in taking a Macedonian town, a full-blown campaign was not on the cards due to the harsh terrain and imminent change in the weather. The war was renewed in the spring of 199 BC, the legions led by a seasoned politician and justice of the war with Hannibal, Sulpicius Galba. Smashing past Philip’s phalanx in a mountain pass without defeating it utterly, the Roman army marched eastward into Macedon. A game of cat and mouse ensued over the summer, with each side seeking battle on its own terms. A victory for the Romans at Ottolobus, when Philip almost lost his life, was countered by a Macedonian win at Pluinna. Harvest-time arrived without a conclusive outcome. Far from their base at Apollonia, with supply lines at risk of being cut by snow or the Macedonians, Galba took the sensible option and retreated to the coast.

In many ways, the politics of two thousand years ago were no different to today. The newly-elected man always likes to take control. Soon after his return to Apollonia, Galba found himself being supplanted by the consul Villius. He in turn was replaced just months later by a more formidable figure, Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Thirty years old, extraordinarily young to command a large army, Flamininus took the invasion in his stride. A lover of all things Greek, he could speak and write the language as well – something unusual for Romans of the time.

His initial attempts to enter Macedon failed, however, and in the spring of 198 BC a 40-day standoff in the narrow Aous valley (the modern-day River Vjosa) unfolded, with his legionaries unable to push past the Macedonian fortifications. In scenes reminiscent of Thermopylae, the deadlock was broken by a local shepherd who led the Romans around Philip’s position. Attacked from front and rear, his troops fell back in panic. Flamininus’ legions swept into western Macedon and onward to fertile Thessaly. Although Philip lost large swathes of territory, his phalanx delivered a mighty setback to the Roman army soon after at the fortress of Atrax. Once again, with autumn approaching, the war proper was put on hold until the following spring.

Prolonged negotiations during the winter months saw Philip’s attempts to broker a peace settlement thwarted by Flamininus’ trickery. When the campaign began again in the spring of 197 BC, a showdown was inevitable. After a few weeks of marching and countermarching by Philip and Flamininus in central Thessaly, battle was joined (almost by accident) at Cynoscephalae, hills known as The Dogs’ Heads. Invincible on flat ground as long as its flanks were protected, the phalanx was dangerously exposed on hillsides. Highly manoeuvrable, veterans of the Hannibalic war, the legionaries wreaked a terrible slaughter.

A negotiated settlement saw Philip remain as king of Macedon, in the main to serve as a buffer against the threat of the Seleucid Empire to the east, but the fate of the Greek city states who had aided and abetted the Roman invasion was the most ironic. Although their freedom was proclaimed by Flamininus at the Isthmian games in 196 BC, they were soon to realise that they had merely exchanged one master for another. Not for hundreds of years would the Greeks rule themselves again.

No comments:

Post a Comment