|

|

|

|

|

An unidentified Canadian soldier, who is armed with a Thompson machine gun, escorting a German prisoner who was captured during Operation JUBILEE, the Dieppe raid. England, 19 August 1942 |

|

| The Dieppe Raid, also known as the Battle of Dieppe, Operation Rutter and, later, Operation Jubilee, was a Second World WarAllied attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe. The raid took place on the northern coast of France on 19 August 1942. The assault began at 5:00 a.m. and by 10:50 a.m. the Allied commanders were forced to call a retreat. Over 6,000 infantrymen, predominantly Canadian, were supported by limited Royal Navy and large Royal Air Force contingents. The objective of the raid was discussed by Churchill in his war memoirs:

Objectives included seizing and holding a major port for a short period, both to prove it was possible and to gather intelligence from prisoners and captured materials, including naval intelligence in a hotel in town and a radar installation on the cliffs above it. Although neither were completely successful, some knowledge was gained while assessing the German responses. The Allies also wanted to destroy coastal defences, port structures and all strategic buildings. The raid could have given a morale boost to the troops, Resistance, and general public, while assuring the Soviet Union of the commitment of the United Kingdom and the United States. No major objectives of the raid were accomplished. A total of 3,623 of the 6,086 men (almost 60%) who made it ashore were either killed, wounded, or captured. The Royal Air Force failed to lure the Luftwaffe into open battle, and lost 96 aircraft (at least 32 to flak or accidents), compared to 48 lost by the Luftwaffe.[2] The Royal Navy lost 33 landing craft and one destroyer. The events at Dieppe later influenced preparations for the North African (Operation Torch) and Normandy landings (Operation Overlord). In the immediate aftermath of the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Forces from Dunkirk in May 1940, the British started on the development of a substantial raiding force under the umbrella of Combined Operations. This was accompanied by development of techniques and equipment for amphibious warfare.In late 1941 a scheme was put forward for the landing of 12 divisions around Le Havre based on a withdrawal of German troops to counter Soviet success in the east. From this came a proposed test of the scheme in the form of "Operation Rutter". Rutter was to test the feasibility of capturing a port in the face of opposition, the investigation of the problems of operating the invasion fleet, and testing equipment and techniques of the assault.[3] Dieppe, a coastal town in the Seine-Maritime department of France, is built along a long cliff that overlooks the English Channel. The River Scie is on the western end of the town and the River Arques flows through the town and into a medium-sized harbour. In 1942, the Germans had demolished some seafront buildings to aid in coastal defence and had set up two large artillery batteries at Berneval-le-Grand and Varengeville. One important consideration for the planners was that Dieppe was within range of the Royal Air Force's fighter aircraft.[4] There was also intense pressure from the Soviet government to open up a second front in Western Europe. By 1942, Operation Barbarossa had failed; however, the Germans were deep into Soviet territory. Joseph Stalin himself demanded that the Allies create a second front in France to force the Germans to move at least 40 divisions away from the Eastern Front to remove some of the pressure on the Red Army.[5] [edit]Daily Telegraph crosswordOn 17 August 1942, the clue "French port (6)" appeared in the Daily Telegraph crossword (compiled by Leonard Dawe), followed by the solution, "Dieppe" the next day; on 19 August, the raid on Dieppe took place.[6] The War Office suspected that the crossword had been used to pass intelligence to the enemy and called upon Lord Tweedsmuir, then a senior intelligence officer attached to the Canadian Army, to investigate the crossword. Tweedsmuir, the son of John Buchan the author, later commented:

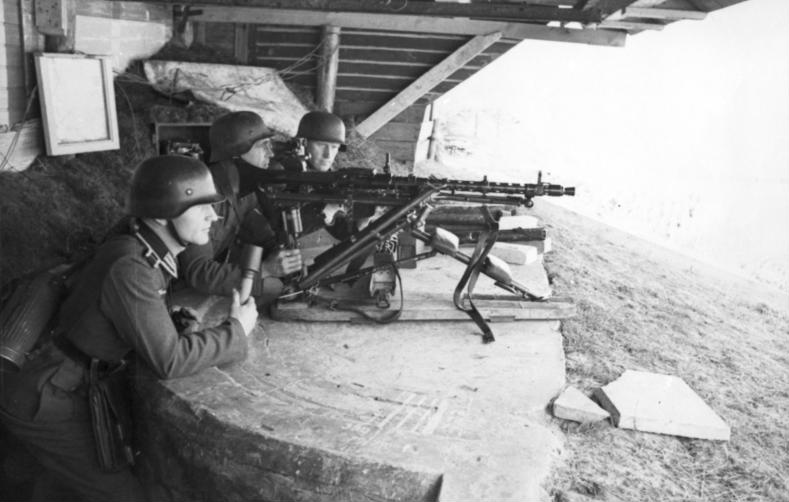

A similar crossword coincidence occurred in May 1944, prior to D-Day. Multiple terms associated with Operation Overlord (including the word "Overlord" itself) appeared in the Daily Telegraph crossword (also written by Dawe), and after another investigation by MI5 this turned out to be a remarkable coincidence as well. Further to this, a former student identified that Dawe frequently requested words from his students, many of whom were children in the same area as US military personnel.[8] [edit]PlanFurther information: Operation Jubilee order of battle The Dieppe raid was a major operation planned by Vice-Admiral Lord Mountbatten of Combined Operations Headquarters. The attacking force would consist of around 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British troops, and 50 United States Rangers.[9] Originally conceived in April 1942 by Combined Operations Headquarters and code named "Operation Rutter", the Allies planned to conduct a major division-sized raid on a German-held port on the French Channel coast and to hold it for the duration of at least two tides. They would effect the greatest amount of destruction of enemy facilities and defences before withdrawing. This original plan was approved by the chiefs of staff in May 1942. It included British parachute units attacking German artillery batteries on the headlands on either side of the Canadians who would carry out a frontal assault from the sea.[10] The parachute operation was later cancelled and instead No. 3 Commando and No. 4 Commando would land by sea and attack the artillery batteries.[9] [edit]Land componentUnder pressure from the Canadian government to ensure that Canadian troops saw some action, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, commanded by Major General John Hamilton Roberts, was selected for the main force.[9] The troops were drawn from Combined Operations and South-Eastern Command, under Lieutenant General Bernard Law Montgomery. The plan called for a frontal assault, without any heavy preliminary air bombardment. The absence of a sufficient bombardment was one of the main reasons for the operation's failure, and various reasons have been given to explain why one was specifically excluded. British and Canadian officials supposedly withheld the use of air and naval bombardments in an attempt to limit casualties of French civilians in the port-city core.[11] The planners of the Dieppe Raid feared that unjustifiable civilian losses would anger and further alienate the Vichy government; an unattractive option considering the intent ofOperation Torch not three months later.[11] Maj. Gen. Roberts, the military force commander, is also said to have argued that a bombardment would make the town streets impassable, and thus hinder the assault after it had broken out of the beaches.[12] The Dieppe landings were planned on six beaches: four in front of the town itself, and two to the eastern and western flanks respectively. From east to west, the beaches were codenamed Yellow, Blue, Red, White, Green and Orange. The Royal Regiment of Canada would land on Blue beach. The main landings would take place on Red and White beaches by the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Essex Scottish Regiment, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, A Commando Royal Marines and the 14th Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)). The South Saskatchewan Regiment and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada would land on Green beach.[9] Location of the raid Armoured support was provided by the 14th Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)) with 58 of the new Churchill tanks, to be delivered using the new landing craft tank (LCT).[13] The tanks had a mixture of armament with QF 2 pounder gun–armed tanks fitted with a close support howitzer in the hull operating alongside QF 6 pounder–armed tanks. In addition, three of the Churchills were equipped with flame-thrower equipment and all had adaptations enabling them to operate in the shallow water near the beach. [edit]Naval and air supportThe Royal Navy would supply 237 ships and landing craft.[9] However, pre-landing naval gunfire support was limited, consisting of six Hunt-class destroyers with 4-inch guns. This was because of the reluctance of First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound to risk capital ships in an area that he believed to be vulnerable to attacks by German aircraft.[14] The Royal Air Force would supply 74 squadrons of aircraft, of which 66 were fighter squadrons.[9] [edit]IntelligenceIntelligence on the area was sparse: there were dug-in German gun positions on the cliffs, but these had not been detected or spotted by air reconnaissance photographers. The planners had assessed the beach gradient and its suitability for tanks only by scanning holiday snapshots, which led to an underestimation of the German strength and of the terrain.[9] The outline plan for "Operation Rutter" (which, although never executed, became the basis for "Operation Jubilee") stated that, "intelligence reports indicate that Dieppe is not heavily defended and that the beaches in the vicinity are suitable for landing infantry, and armoured fighting vehicles at some".[15] [edit]German forcesA German MG34 heavy machine gun emplacement The German forces at Dieppe were on high alert having been warned by French double agents that the British were showing interest in the area. They had also detected increased radio traffic and landing craft being concentrated in the southern British coastal ports.[9] Dieppe and the flanking cliffs were well defended, although the 1,500-strong garrison from the 302nd German Infantry Division comprised the 570th, 571st and 572nd Infantry Regiments, each of two battalions, the 302nd Artillery Regiment, the 302nd Reconnaissance Battalion, the 302nd Anti-tank Battalion, the 302nd Engineer Battalion and 302nd Signal Battalion. They were deployed along the beaches of Dieppe and the neighbouring towns, covering all the likely landing places. In respect to machine guns, mortars and artillery, the city and port was adequately protected with a concentration on the main approach (particularly in the myriad of cliff caves), and with a reserve at the rear. The defenders were stationed not only in the towns themselves, but also between the towns in open areas and highlands that overlooked the beaches. Elements of the 571st Infantry Regiment defended the Dieppe radar station near Pourville and the artillery battery over the Scie river at Varengeville. To the east the 570th Infantry Regiment were deployed near the artillery battery at Berneval. The Luftwaffe forces were Jagdgeschwader 2 (JG2) and Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG26), with 200 fighters, mostly the Fw 190 and about 100 bombers fromKampfgeschwader 2 (KG2), Kampfgeschwader 45 (KG45), and Kampfgeschwader 77 (KG77), mostly Dornier 217s. [edit]Initial landingsThe Allied fleet left the south coast of England on the night of 18 August 1942, with the Canadians leaving from the Port of Newhaven. The fleet of eight destroyers and accompanying motor gun boats to escort the landing craft and motor launches were preceded by minesweepers that cleared paths through the English Channel for them. The initial landings began at 04:50 on 19 August, with attacks on the two artillery batteries on the flanks of the main landing area. These included Varengeville by No. 4 Commando, Pourville by the South Saskatchewan Regiment and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, Puys by the Royal Regiment of Canada, and Berneval by No. 3 Commando. On their way in, the landing craft and escorts heading towards Puys and Berneval ran into a small German convoy and exchanged fire at 03:48.[9] [edit]Yellow BeachNo. 3 Commando men who unlike No. 4 Commando wore steel helmets during the raid. The mission for Lieutenant Colonel John Durnford-Slater and No. 3 Commando was to conduct two landings 8 miles (13 km) east of Dieppe to silence the coastal battery near Berneval. The battery could fire upon the landing at Dieppe 4 miles (6.4 km) to the west. The three 170 mm (6.7 in) and four 105 mm (4.1 in) guns of 2/770 Batterie had to be out of action by the time the main force approached the main beach. The craft carrying No. 3 Commando, approaching the coast to the east, were not warned of the approach of a German coastal convoy that had been located by British "Chain Home" radar stations at 21:30. German S-boats escorting a German tanker torpedoed some of the landing craft and disabled the escorting Steam Gun Boat 5. Subsequently, Motor Launch 346 and Landing Craft Flak 1 combined to drive off the German boats but the group was dispersed, with some losses, and the enemy's coastal defences were alerted. Only 18 commandos got ashore at the right place. They reached the perimeter of the battery via Berneval and engaged their target with small arms fire. Although unable to destroy the guns, their sniping for a time managed to distract the battery to such good effect that the gunners fired wildly and there was no known instance of this battery sinking any of the assault convoy ships off Dieppe. The commandos were eventually forced to withdraw in the face of superior enemy forces.[9][10] [edit]Orange BeachThe mission for Lieutenant Colonel Lord Lovat and No. 4 Commando (including 50 United States Army Rangers) was to conduct two landings 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Dieppe to neutralize the coastal battery near Varengeville. Landing on the right flank in force they climbed the steep slope, and attacked and neutralized their target, the artillery battery of six 150 mm guns. This was the only success of Operation Jubilee.[9] The commando then withdrew at 07:30 as planned.[4] Most of No. 4 safely returned to England. This portion of the raid was considered a model for future commando raids. Lord Lovat was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his part in the raid,[16] and Captain Patrick Porteous No. 4 Commando, was awarded the Victoria Cross.[17][18][19] [edit]Blue beachCanadian dead on Blue beach at Puys. Trapped between the beach and high sea wall (fortified with barbed wire), they made easy enfilade targets for MG34machineguns in a German bunker. The bunker firing slit is visible in the distance, just above the German soldier's head. The naval engagement between the small German convoy and the craft carrying No. 3 Commando had alerted the German defenders at Blue beach.[4]The landing near Puys by the Royal Regiment of Canada plus three platoons from the Black Watch of Canada and an artillery detachment was tasked to neutralize machine gun and artillery batteries protecting the Dieppe beach.[4] They were delayed by 20 minutes and the smoke screens that should have hidden their assault had lifted. With the advantage of surprise and darkness lost, the Germans had manned their defensive positions in preparation for the landings.[4] The well-fortified German forces held the Canadian forces that did land on the beach. As soon as they reached the shore, the Canadians found themselves pinned against the seawall and unable to advance.[4] The Royal Regiment of Canada was annihilated. Of the 556 men in the regiment, 200 were killed and 264 captured.[4] [edit]Green beachOn Green beach at the same time that No. 4 Commando had landed, the South Saskatchewan Regiment was headed towards Pourville. They beached at 04:52 without having been detected. The regiment managed to leave their landing craft before the Germans could open fire. Unfortunately, on the way in, some of the landing craft had drifted off course and most of the battalion found themselves west of the River Scie rather than east of it. Because they had been landed in the wrong place, the regiment, whose objective was the hills east of the village, had to enter Pourville to cross the river by the only bridge.[4] Before the Saskatchewans managed to reach the bridge, the Germans had positioned machine guns and anti-tank guns there which stopped their advance. With the regiment's dead and wounded piling up on the bridge, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Cecil Ingersoll Merritt, the commanding officer, attempted to give the attack impetus by repeatedly and openly crossing the bridge, in order to demonstrate that it was feasible to do so.[20] However, despite the assault resuming, the South Saskatchewans and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, who had landed beside them, were unable to reach their target.[4][9] While the Camerons did manage to penetrate further inland than any other troops that day, they were also soon forced back as German reinforcements rushed to the scene.[9] Both regiments suffered more losses as they withdrew; only 341 men were able to reach the landing craft and embark, and the rest were left to surrender. For his part in the battle, Lieutenant Colonel Merritt was awarded the Victoria Cross.[17] [edit]Pourville radar stationDestroyed landing craft on fire with Canadian dead on the beach. A concrete gun emplacement on the right covers the whole beach. The steep gradient can clearly be judged. One of the objectives of the Dieppe Raid was to discover the importance and accuracy of a German radar station on the cliff-top to the east of the town of Pourville. To achieve this, RAF Flight Sergeant Jack Nissenthall, a radar specialist, was attached to the South Saskatchewan Regiment. He was to attempt to enter the radar station and learn its secrets, accompanied by a small unit of 11 men of the Saskatchewans as bodyguards. Nissenthall volunteered for the mission fully aware that, due to the highly sensitive nature of his knowledge of Allied radar technology, his Saskatchewan bodyguard unit were under orders to kill him if necessary to prevent him being captured. He also carried a cyanide pill as a last resort.[21] After the war, Lord Mountbatten claimed to author James Leasor, when being interviewed during research for the book 'Green Beach', that "If I had been aware of the orders given to the escort to shoot him rather than let him be captured, I would have cancelled them immediately." Nissenthall and his bodyguards failed to enter the radar station due to strong defences, but Nissenthall was able to crawl up to the rear of the station under enemy fire and cut all telephone wires leading to it. This forced the crew inside to resort to radio transmissions to talk to their commanders, transmissions which were intercepted by listening posts on the south coast of England. The Allies were able to learn a great deal about the arrays of German radar stations along the channel coast thanks to this one simple act, which helped to convince Allied commanders of the importance of developing radar jamming technology. Of this small unit, only Nissenthall and one other returned safely to England. After the war Jack Nissenthall shortened his surname to Nissen.[22][23] [edit]Main Canadian landingsCanadian wounded and abandonedChurchill tanks after the raid. A landing craft is on fire in the background. Preparing the ground for the main landings, four destroyers were bombarding the coast as landing craft approached. At 05:15 hours, they were joined by five RAF Hurricane squadrons who bombed the coastal defences and set a smoke screen to protect the assault troops. Between 05:20 and 05:23, 30 minutes after the initial landings the main frontal assault by the Essex Scottish and the Hamilton Light Infantry started. Their infantry were meant to be supported by Churchill tanks of the 14th Canadian Armoured Regiment landing at the same time but they arrived on the beach late. As a result the two infantry regiments had to attack without armour support. They were met with heavy machine gun fire from emplacements dug into the overlooking cliffs. Unable to clear the obstacles and scale the seawall, they suffered heavy losses.[4][9] When the tanks eventually arrived only 29 were landed. Two of those sank in deep water, and 12 more became bogged down in the soft shingle beach.[4] Only 15 of the tanks made it up to and across the seawall.[4]Once they crossed the seawall, they were confronted by a series of tank obstacles that prevented their entry into the town. Blocked from going further, they were forced to return to the beach where they provided fire support for the now retreating infantry. None of the tanks managed to return to England. All the crews that landed were either killed or captured.[4] Daimler Dingo armoured car and twoChurchill tanks bogged down on the shingle beach. The nearest Churchill tank has a flame thrower mounted in the hull, the rear tank has lost a track. Both have attachments to heighten their exhausts for wading through the surf. Unaware of the situation on the beaches because of a smoke screen laid by the supporting destroyers, Major General Roberts sent in the two reserve units: the Fusiliers Mont-Royal and the Royal Marines. At 07:00 the Fusiliers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Dollard Ménard in 26 landing craft sailed towards their beach. They were heavily engaged by the Germans, who hit them with heavy machine gun, mortar and grenade fire, and destroyed them; only a few men managed to reach the town.[4] Those men were then sent in towards the centre of Dieppe and became pinned down under the cliffs and Roberts ordered the Royal Marines to land in order to support them. Not being prepared to support the Fusiliers the Royal Marines had to transfer from their gunboats and motor boat transports onto landing craft. The Royal Marine landing craft were heavily engaged on their way in with many destroyed or disabled. Those Royal Marines that did reach the shore were either killed or captured. As he became aware of the situation the Royal Marine commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Phillipps, stood up on the stern of his landing craft and signalled for the rest of his men to turn back. He was killed a few moments later.[9] During the raid, a mortar platoon[24] from the Calgary Highlanders commanded by Lt. F. J. Reynolds was attached to the landing force, but stayed offshore after the tanks on board (code-named Bert and Bill) landed. Sergeants Lyster and Pittaway[25] were Mentioned in Despatches for their part in shooting down two German aircraft, and one officer of the regiment was killed while ashore with a brigade headquarters.[26] At 11:00, under heavy fire, the withdrawal from the main landing beaches began and was completed by 14:00.[9] [edit]Air battleThe Allied air operations supporting Operation Jubilee resulted in some of the fiercest air battles since 1940. The RAF's main objectives were to throw a protective umbrella over the amphibious force and beach heads and also to force the Luftwaffe forces into a battle of attrition on the Allies' own terms. Some 48 fighter squadrons of Spitfires were committed, with eight squadrons ofHurricane fighter-bombers, four squadrons of reconnaissance Mustang Mk Is and seven squadrons of No. 2 Group light bombers involved.[27] Opposing these forces were some 120 operational fighters of Jagdgeschwader 2 and 26 (JG 2 and JG 26), the Dornier Do 217s of Kampfgeschwader 2 and various anti-shipping bomber elements of III./KG 53, II./Kampfgeschwader 40 (KG40) and I./KG 77. Although initially slow to respond to the raid, the German fighters soon made their presence felt over the port as the day wore on. While the Allied fighters were moderately successful in protecting the ground and sea forces from aerial bombing, they were hampered by operating far from their home bases. The Spitfires in particular were at the edge of their ranges, with some only being able to spend five minutes over the combat area.[27] [edit]"Enigma Pinch" theoryResearch undertaken over a 15-year period by military historian David O’Keefe, uncovered 100,000 pages of classified British military archival files that documented a "pinch" mission overseen byIan Fleming (best known later as author of the James Bond action espionage books), that coincided with the Dieppe Raid. No. 30 Commandos were sent into Dieppe to steal one of the new German 4-rotor Enigma code machines, plus associated code books and rotor setting sheets. The Naval Intelligence Division (NID) planned the "pinch" raid with the intention to pass such items to cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park to assist with the Ultra project.[28] Introduction of the 4-rotor machine was preventing cryptanalysis of the Enigma, so the Allies were eager to get their hands on one to discover (and exploit) any weaknesses in the new system. However, the raid was a failure and Bletchley Park did not receive its Enigma machine.[29] [edit]AftermathCanadian dead at Dieppe, August 1942 Canadian prisoners being led away through Dieppe after the raid. Credit: Library and Archives Canada / C-014171 Of the nearly 5,000-strong Canadian contingent, 3,367 were killed, wounded or taken prisoner, an exceptional casualty rate of 68%.[30] The 1,000 British Commandos lost 247 men. The Royal Navy lost one destroyer (HMS Berkeley) and 33 landing craft, suffering 550 dead and wounded. The RAF lost 106 aircraft to the 48 lost by the Luftwaffe. The German Army had 591 casualties.[9] While the Canadian contingent fought bravely in the face of a determined enemy, it was ultimately circumstances outside their control which sealed their fate.[31] Despite criticism concerning the inexperience of the Canadian regiment that was engaged in battle, scholars have noted that even seasoned professionals would have been hard-pressed under the deplorable conditions suggested by their superiors. The commanding officers who designed the raid on Dieppe had not envisaged such losses.[31] This was, after all, one of the first attempts by the Western Allies on a German-held port city. As a consequence, planning from the highest ranks in preparation for the raid was minimal. Critical strategic and tactical errors were made which resulted in scores of Allied (particularly Canadian) deaths. The losses at Dieppe were claimed to be a necessary evil.[31] Mountbatten later justified the raid by arguing that lessons learned at Dieppe in 1942 were put to good use later in the war. He later claimed, “I have no doubt that the Battle of Normandy was won on the beaches of Dieppe. For every man who died in Dieppe, at least 10 more must have been spared in Normandy in 1944." In direct response to the raid on Dieppe, Winston Churchill remarked that, “My Impression of 'Jubilee' is that the results fully justified the heavy cost” and that it “was a Canadian contribution of the greatest significance to final victory.”[32] The amphibious assaults in North Africa followed three months after the Dieppe Raid, and the successful Normandy landings took place two years later. [edit]German propagandaBritish prisoners at Dieppe, August 1942 Dieppe was in many ways a victory for German propaganda. The Third Reich largely described the Dieppe raid as a military joke, noting the amount of time needed to design such an attack, combined with the incredible losses suffered by the Allies, pointed only to incompetence.[11] The propaganda value of German material regarding the raid was enhanced by the fact that British official information was slow in being published. This meant that Allied media were forced to carry announcements from German sources.[33] These attempts were made to rally the morale of the German people despite the growing intensity of the Allied strategic bombing campaign on German cities as well as a great many casualties lost daily on the Eastern Front.[11] [edit]The air battleWhile Fighter Command claimed to have inflicted heavy casualties on the Luftwaffe the ultimate balance sheet showed Allied aircraft losses as being serious. Final figures are disputed; one source indicates that losses amounted to 106 from enemy action: 88 fighters (including 44 Spitfires) 10 reconnaissance aircraft and eight bombers, and that 14 other RAF aircraft were struck off from other causes such as accidents.[34] Other sources suggest that as many as 28 bombers were lost, and that the overall figure for destroyed and damaged Spitfires was 70.[2] Against this, 48 Luftwaffeaircraft were lost. Included in that total were 28 bombers, half of them Dornier Do 217s from KG2. One of the two Jagdgeschwader, JG 2, lost 14 Fw 190s and eight pilots killed. JG 26 lost six Fw 190s with their pilots.[35] [edit]POW policiesBrigadier William Wallace Southam brought ashore his copy of the assault plan, classified as a secret document. Although he attempted to bury it under the pebbles at the time of his surrender, he was spotted and the plan retrieved by the Germans. The plan, later criticised for its size and needless complexity, contained orders to shackle prisoners.[citation needed] The Germans later also received reports of the bodies of German prisoners with their hands tied washing ashore after the Canadian withdrawal. When this was brought toHitler's attention, he ordered the shackling of Canadian prisoners, which led to a reciprocating order by British and Canadian authorities for German prisoners being held in Canada.[36] Though the Canadians were opposed to the plan, which they considered a danger to Canadian POWs in German hands, they reluctantly implemented it to maintain unity with the British. Nevertheless, as the Canadians expected, the shackling order led directly to trouble and the only known uprising at a Canadian prisoner of war camp during World War II, the so-called "Battle of Bowmanville". Subsequent to this event, the Canadian and German orders both eventually lost momentum in POW camps and were eventually abandoned after intercession by the International Red Cross.[37] The Germans decided to reward the town for not helping in the raid by freeing POWs from Dieppe in their custody, and on 12 September, a train carrying around 1,500 French POWs arrived at Dieppe. In addition, as a reward for what he called the town residents' "perfect discipline and calm", Hitler gave the town a gift of 10 million francs, to be used to repair damage caused during the raid.[38] [edit]Extent of German preparednessCanadian and British dead at Dieppe, August 1942 The scale of failure of the operation has led to a discussion around whether the Germans knew of the raid in advance. In some ways, this would be unsurprising; security in the area from which the operation was launched was poor, and 'a good deal could be deduced simply by shrewd observation and careful attention to careless talk'.[39] Additionally, since June 1942, the BBC had been broadcasting warnings to French civilians of a "likely" war, urging them to quickly evacuate the Atlantic coastal districts of occupied France.[6][40][41] Indeed, on the day of the raid itself, the BBC announced it, albeit at 0800, after the landings themselves had taken place.[42] First-hand accounts and memoirs of many Canadian veterans who documented their experiences on the shores of Dieppe remark about the preparedness of the German defences as if they knew of the raid ahead of time, citing the fact that, for example, upon touching down on the Dieppe shore, the landing ships were immediately shelled with the utmost precision as troops began exiting. The volume and tone of these accounts meant that a Canadian government report at the end of 1942 concluded that 'The Germans seem to have had ample warning of the raid and to have made thorough preparations for dealing with it.'[43] Commanding officer Lt. Colonel Labatt testified to having seen markers used for mortar practice, which appeared to have recently been placed, on the beach.[44] The belief that the Germans had received accurate and detailed warning of the attacks have been strengthened by subsequent accounts of both German and Allied POWs. Major C. E. Page, while interrogating a German soldier, found out that four machine gun battalions were brought in "specifically" in anticipation of a raid. There are numerous accounts of interrogated German prisoners, German captors, and French citizens who all conveyed to Canadians that the Germans had been preparing for the anticipated Allied landings for weeks.[45][46] However, there is a view that while it is likely the Germans were expecting an attack somewhere on the French shoreline, evidence of an expectation of an attack at Dieppe in particular, at that particular time, is less conclusive. Exponents of this view point out that elements of the Canadian forces, such as at Green beach, landed without trouble. Lt Col Merrit has been quoted as saying 'How could the Germans have known if we got in on our beach against defences which were unmanned?'[47] No 4 Commando's troops also reported that they achieved surprise against the gun batteries they were tasked with destroying.[48] Under this view, the statements by German POWs that the raid was fully expected are explained as being propaganda.[49] [edit]Dieppe War CemeteryThe current grave markers in the Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery Allied dead were initially buried in a mass grave, but the bodies were subsequently disinterred and reburied at Vertus Wood on the edge of the town.[50]The present Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery headstones have been placed back-to-back in double rows, the norm for a German war cemetery, but unusual for Commonwealth War Graves Commission sites. When the Allies liberated Dieppe as part of Operation Fusilade in 1944, the grave markers were replaced but the layout was left unchanged to avoid disturbing the remains. [edit]Honours and awardsThree Victoria Crosses were awarded for the operation: to Captain Porteous, No. 4 Commando; the Reverend John Weir Foote, padre to Royal Hamilton Light Infantry; and Lieutenant Colonel Merritt of the South Saskatchewan Regiment. Porteous was severely wounded; both Foote and Merritt becameprisoners of war. Despite the failure of the operation, Maj Gen Roberts was awarded the DSO. [edit]German analysisThe capture of a copy of the Dieppe plan by the Germans allowed them to carry out a thorough analysis of the operation. Senior German officers were unimpressed; Gen. Conrad Haase considered it "incomprehensible" that a single division was expected to be able to overrun a German regiment that was supported by artillery. He added that, "the strength of naval and air forces was entirely insufficient to suppress the defenders during the landings". Gen. Kuntzen believed it "inconceivable" that the Pourville landings were not reinforced with tanks.[51] The Germans were also unimpressed by the specifications of Churchill tanks left behind after the withdrawal. One report assessed that, "in its present form the Churchill is easy to fight". Its gun was described as "poor and obsolete", and the armour was compared unfavourably with that used in German and Soviet tanks.[52] The Germans recognised that the Allies were certain to learn some lessons from the operation, with Von Rundstedt observing that, "Just as we are going to evaluate these experiences for the future so is the assaulting force ... perhaps even more so as it has gained the experience dearly. He will not do it like this a second time!"[53] [edit]German propaganda photos taken hours after the failed Dieppe Raid[edit]Allied analysisThe lessons learned at Dieppe essentially became the textbook of “what not to do” in future amphibious operations, and laid the framework for the Normandy landings two years later. Most notably, Dieppe highlighted:

As a consequence of the lessons learned at Dieppe, the British developed a whole range of specialist armoured vehicles which allowed their engineers to perform many of their tasks protected by armour, most famously Hobart's Funnies. The operation showed major deficiencies in RAF ground support techniques, and this led to the creation of a fully integrated Tactical Air Force to support major ground offensives.[54] Another effect of the raid was change in the Allies' previously held belief that seizure of a major port would be essential in the creation of a second front. Their revised view was that the amount of damage that would be done to a port by the necessary bombardment to take it, would almost certainly render it useless as a port afterwards. As a result, the decision was taken to construct prefabricated harbours, codenamed "Mulberry", and tow them to lightly defended beaches as part of a large-scale invasion.[12] Howard Large, a Canadian veteran of Dieppe who was wounded and captured in the Dieppe Raid, said “They were nuts," of the Allied planners and force commanders who thought up the attack |

Commanders returning from Dieppe Raid

Final exercise prior to assault landing at Dieppe

Final exercise prior to assault landing at Dieppe

Final exercise prior to assault landing at Dieppe

Holy communion parade on streets of Dieppe where Germans herded Canadian prisoners in 1942

Major J. M. Figott and members of his company of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry kneeling at the graves of Canadian soldiers killed at Dieppe on 19 August 1942. Dieppe, France, 1 September 1944

British Commandos of No.3 or No.4 Commando (British Army) who took part in Operation JUBILEE, the Dieppe raid, returning to England, 19 August 1942

ldiers who took part in Operation JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe, returning to England, 19 August 1942

Soldiers who took part in Operation JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe, disembarking from a Royal Navy destroyer in England, 19 August 1942

Soldiers who took part in Operation JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe, returning to England, 19 August 1942

German soldiers who were captured during Operation JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe, disembarking in England, 19 August 1942

Unidentified crewman with Douglas BOSTON aircraft of the Royal Air Force which took part in Operation JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe

Dieppe Raid. 19 August 1942. Evacuation of wounded

Troops who took part in the raid on Dieppe, France, 19 August 1942 |

1 comment:

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

Post a Comment