| | |  |

| | | | King Henri IV de France was the Protestant figure who was famous, according to legend, for saying « Paris vaut bien une messe» — Paris is well worth a mass — when he decided, for political reasons, to embrace Catholicism as king. Henri was by heredity the king of Navarre, a small, contested territory straddling the Pyrenees mountains between France and Spain.

Henri de Navarre was formally recognized as the legitimate king of France in 1589 by heirless French King Henri III, his brother-in-law and cousin, who was on his deathbed after suffering wounds inflicted upon him by a fanatical assassin. The new king had to convince the majority Catholics to give him their allegiance, so he renounced Protestantism.

He came to the throne at the end of the religious wars between French Catholics and Protestants. In 1598 Henri signed the Edict of Nantes, giving Protestants the legal right to practice their religion in France. He was also the king who said, again according to legend, that his goal was to make sure that every French family had « une poule au pot » — a “chicken in the pot,” or a stewed chicken — for dinner every Sunday. Henry IV (13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), Henri-Quatre also known by the epithet "Good King Henry", was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 to 1610 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first French monarch of the House of Bourbon. Baptised as a Catholic but raised in the Protestant faith by his mother Jeanne d'Albret, Queen of Navarre, he inherited the throne of Navarre in 1572 on the death of his mother. As a Huguenot, Henry was involved in the French Wars of Religion, he barely escaped assassination at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, and he later led Protestant forces against the royal army. As a French "prince of the blood" by reason of his descent from King Louis IX, he ascended the throne of France upon the death of his childless uncle-in-law Henry III in 1589. In accepting the throne, he found it prudent to abjure his Calvinist faith. Regardless, his coronation was followed by a four-year war against the Catholic League to establish his legitimacy. As a pragmatic politician (in the parlance of the time, a politique), he displayed an unusual religious tolerance for the time. Notably, he promulgated the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which guaranteed religious liberties to Protestants, thereby effectively ending the Wars of Religion. He was assassinated by François Ravaillac, a fanatical Catholic, and was succeeded by his son Louis XIII.[1] Considered as an usurper by Catholics and as a traitor by Protestants, Henry was hardly accepted by the population and escaped at least 12 assassination attempts.[2] An unpopular king during his reign, Henry's popularity greatly improved posthumously.[3] The "Good King Henry" (le bon roi Henri) was remembered for his geniality and his great concern about the welfare of his subjects. He was celebrated in the popular song Vive le roi Henri and in Voltaire's Henriade. Henry was born in Pau, the capital of the joint Kingdom of Navarre with the sovereign principality of Béarn.[4] His parents were Queen Joan III of Navarre (Jeanne d'Albret) and King Antoine of Navarre.[5] Although baptized as a Roman Catholic, Henry was raised as a Protestant by his mother,[6] who had declared Calvinism the religion of Navarre. As a teenager, Henry joined the Huguenot forces in the French Wars of Religion. On 9 June 1572, upon his mother's death, he became King of Navarre.

Henry III of France on his deathbed designating Henry III of Navarre as his successor in 1589. First marriage and Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre[edit] At Queen Jeanne's death, it was arranged for Henry to marry Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici. The wedding took place in Paris on 18 August 1572.[8] on the parvis of Notre Dame Cathedral. On 24 August, the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre began in Paris. Several thousand Protestants who had come to Paris for Henry's wedding were killed, as well as thousands more throughout the country in the days that followed. Henry narrowly escaped death thanks to the help of his wife and his promise to convert to Catholicism. He was made to live at the court of France, but he escaped in early 1576. On 5 February of that year, he formally abjured Catholicism at Tours and rejoined the Protestant forces in the military conflict.[9] Wars of Religion

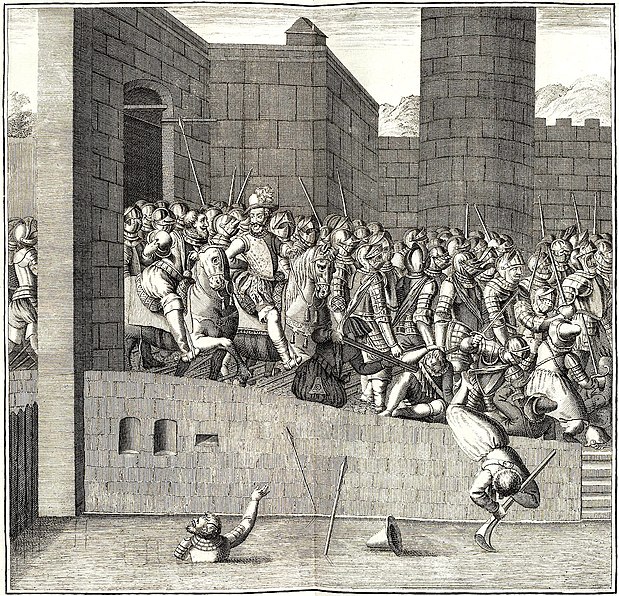

Henry at the Battle of Arques At that time, the royal army was in a shambles and Henry IV could only count on barely 20,000 men to conquer a rebellious country. In order to accomplish this task, he divided his troops into three commands: Henri I d'Orléans, Duke of Longueville(1568-1595) for Picardy, Jean VI d'Aumont for Champagne and Henry IV for Normandy (where he awaited reinforcements fromElizabeth I of England). On 6 August 1589, Henry set up camp with 8,000 men at the port of Dieppe. The Duke of Mayenne sought to take back this key strategic port from Henry's forces and to drive him from Normandy. He drew together 35,000 troops, plus Cambrésis militias, Lorraine troops led by the Marquis de Pont-à-Mousson and a contingent of Spanish troops to attack the city.[1] Knowing that an attack against an army of this size would be pointless, and that staying in the city of Dieppe would be suicidal, Henry (after consulting with the Duke of Longueville and the Duke d'Aumont) decided to go to the city of Arques (today called "Arques-la-Bataille") and to construct important military defenses (raising of areas, rebuilding fortifications). The battle

The ruins of the château of Arques, today. Between the 15 September and the 29 September 1589, the troops of the Catholic League launched several attacks on Arques and the surrounding areas, but the Duke of Mayenne's forces were countered by royal artillery. The attacks were extremely deadly for both sides, and soon Henry IV's side found itself undermanned. Henry's rescue came from the sea on the 23 September: 4,000 English soldiers sent by Queen Elizabeth had left England in several waves over three days. Seeing these reinforcements, the Duke of Mayenne decided to retreat, leaving Henry IV victorious. After the battle of Arques, Henri IV snatched a short rest in a neighbouring chateau, and before riding away he scratched with his diamond the following aspiration on one of the windows: " Dieu gard de mal ma mie. Ce 22 de Septembre 1589

Henry IV at the Battle of Ivry, byPeter Paul Rubens Henry IV had moved rapidly to besiege Dreux, a town controlled by the League. As Mayenne followed intending to raise the siege, Henry withdrew but stayed within sight. He deployed his army on the plain of Saint André between the towns of Nonancourt and Ivry. The army of the Catholic League consisted of citizens led by priests and rebellious nobles, Swiss infantry under Appenzell, pikemen brought from Flanders by Philip, Count of Egmont, and the troopers of the Guise family with the Duke of Mayenne in command. The battle

At first light on 14 March 1590, the two armies engaged. The Duke had 12,000 foot soldiers supported by an assortment of German and Swiss infantry and 4,000 cavalry, 2,000 of whom were Spanish. Henry had only 8,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 men on horseback. Before the battle, the king famously spurred his troops: "Companions! If you today run at risk with me, I will also run at risk with you; I will be victorious or die. God is with us. Look at his and our enemies. Look at your king. Hold your ranks, I beg of you; and if the heat of battle makes you leave them, think also of rallying back: therein lies the key to victory. You will find it among those three trees that you can see over there on your right side. If you lose your ensigns, cornets or flags, do never lose sight of my panache; you will always find it on the road to honour and victory." The action began with a few deadly cannon volleys from the six pieces of the royal artillery, which was under the command of the master, La Guiche. The cavalry of the two sides then clashed with a dreadful force. The Duke of Mayenne followed up with the mercenary troops of the Guelders and Almaine across the open field. The mercenaries, who were mostly sympathetic to the Protestant cause, fired in the air and put their spears in rest. Mayenne charged with such a fury that after a terrible fusillade and a struggle of a full quarter of an hour which left the field covered with dead, following the defection of his mercenaries, the opposing left flank fled and the right was pierced and gave way. Aumont soon overcame the League's light horse and their royalist counterparts retreated under the attack of a Walloon(essentially Belgian) squadron backed up by two squadrons from the League. It was then the turn of the Maréchal d'Aumont, the Duc de Montpensier and the Baron de Biron to charge the foreign cavalry, forcing it into a retreat. Marshal de Biron, in command of the rear-guard, joined up with the king who, without stopping after his victory, had crossed the river Eure in pursuit of the enemy. However, the decisive event took place elsewhere on the battlefield: the King charged the League's lancers, who were unable to get far enough back to use their weapons. Mayenne was driven back, the Duke of Aumale forced to surrender, and the Count of Egmont killed. The Duke of Mayenne had lost the battle. Henry pursued the losers, many of whom surrendered for fear of falling into worse hands, their horses being in no condition to get them away from danger. The countryside was full of Leaguers and Spaniards in flight, with the king's victorious army pursuing and scattering the remnants of the larger groups that dispersed and re-gathered.  Aftermath Aftermath

Henry defeated Mayenne at Ivry so that he would became the only credible claimant to the throne of France. However, he was defeated in many sieges of Paris until he converted to Catholicism in 1593. Henry was advised that the French people would not accept a Protestant king. Thomas Babbington Macaulay wrote a famous poem about the battle, entitled "The Battle of Ivry." It begins: Now glory to the Lord of Hosts, from whom all glories are!

And glory to our Sovereign Liege, King Henry of Navarre!

Henry IV, as Hercules vanquishing the Lernaean Hydra (i.e. the Catholic League), by Toussaint Dubreuil, circa 1600 Henry of Navarre became heir presumptive to the French throne in 1584 upon the death of Francis, Duke of Anjou, brother and heir to the CatholicHenry III, who had succeeded Charles IX in 1574. Because Henry of Navarre was the next senior agnatic descendant of King Louis IX, King Henry III had no choice but to recognise him as the legitimate successor.[10] Salic law barred the king's sisters from inheriting and all others who could claim descent through the female line. Since Henry of Navarre was a Huguenot, the issue was not considered settled in many quarters of the country and France was plunged into a phase of the Wars of Religion known as the War of the Three Henries. Henry III and Henry of Navarre were two of these Henrys. The third was Henry I, Duke of Guise, who pushed for complete suppression of the Huguenots and had much support among Catholic loyalists. Political disagreements among the parties set off a series of campaigns and counter-campaigns that culminated in the Battle of Coutras.[11] In December 1588, Henry III had Henry I of Guise murdered,[12] along with his brother, Louis Cardinal de Guise.[13] This increased the tension further and Henry III was assassinated shortly thereafter by a fanatic monk.[14] Upon the death of Henry III on 2 August 1589, Henry of Navarre nominally became king of France. The Catholic League, however, strengthened by support from outside the country—especially from Spain, was strong enough to force him to the south. He had to set about winning his kingdom by military conquest, aided by money and troops sent by Elizabeth I of England. Henry's Catholic uncle Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon, was proclaimed king by the League, but the cardinal was Henry's prisoner.[15] Henry was victorious at the Battle of Arques and the Battle of Ivry, but failed to take Paris after Siege of Paris in 1590.[16] When the Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, the daughter of Philip II of Spain, whose mother Elisabeth had been the eldest daughter of Henry II of France.[17] The prominence of her candidacy hurt the League, which became suspect as agents of the foreign Spanish. Nevertheless, Henry remained unable to take control of Paris.

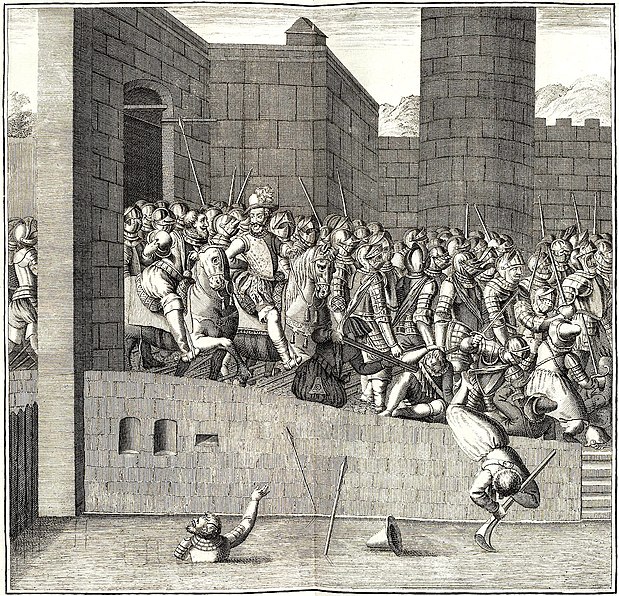

Entrance of Henry IV in Paris, 22 March 1594, with 1,500 cuirassiers "Paris is well worth a Mass" On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of the great love of his life, Gabrielle d'Estrées, Henry permanently renounced Protestantism, thus earning the resentment of the Huguenots and his former ally Queen Elizabeth I of England. He was said to have declared that Paris vaut bien une messe ("Paris is well worth a mass"), although there is some doubt whether he said this, or whether the statement was attributed to him by his contemporaries. His acceptance of Roman Catholicism secured for him the allegiance of the vast majority of his subjects, and he was crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594. In 1598, however, he issued theEdict of Nantes, which granted circumscribed toleration to the Huguenots. Royal styles of

King Henry IV

Par la grâce de Dieu, Roi de France et de Navarre Reference style

His Most Christian Majesty Spoken style

Your Most Christian Majesty Alternative style

Sire Second marriage Henry IV and Marie de Médicis Henry IV and Marie de Médicis Henry's first marriage was not a happy one, and the couple remained childless. Henry and Margaret separated even before Henry succeeded to the throne in August 1589, and Margaret lived for many years in the Château d'Usson in the Auvergne. After Henry became king of France, it was of the utmost importance that he provide an heir to the crown in order to avoid the problem of a disputed succession. Henry favoured the idea of obtaining an annulment of his marriage to Margaret and taking Gabrielle d'Estrées as his bride; after all, she had already borne him three children. Henry's councilors strongly opposed this idea, but the matter was resolved unexpectedly by Gabrielle's sudden death in the early hours of 10 April 1599, after she had given birth to a premature and stillborn son. His marriage to Margaret was annulled in 1599, and he then married Marie de' Medici in 1600. For the royal entry of Marie into Papal Avignon on 19 November 1600, the Jesuit scholars bestowed on Henry the title of the Hercule Gaulois ("Gallic Hercules"), justifying the extravagant flattery with a genealogy that traced the origin of the House of Navarre to a nephew of Hercules' son Hispalus.[

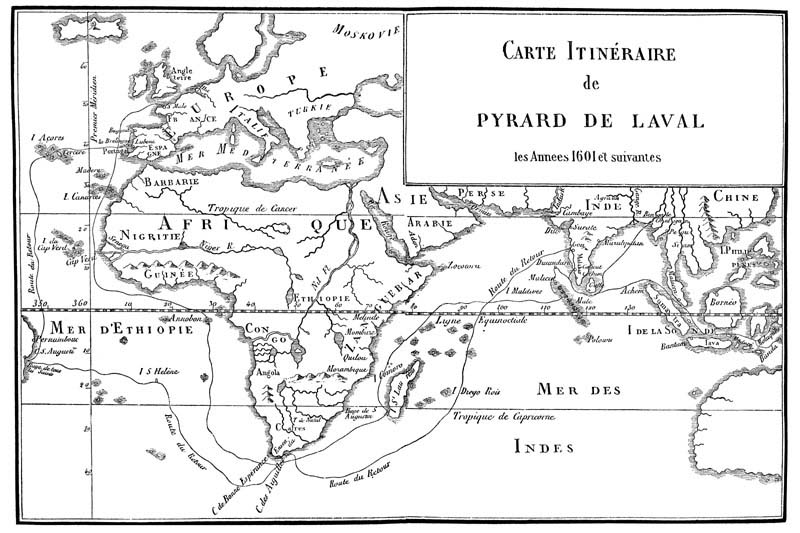

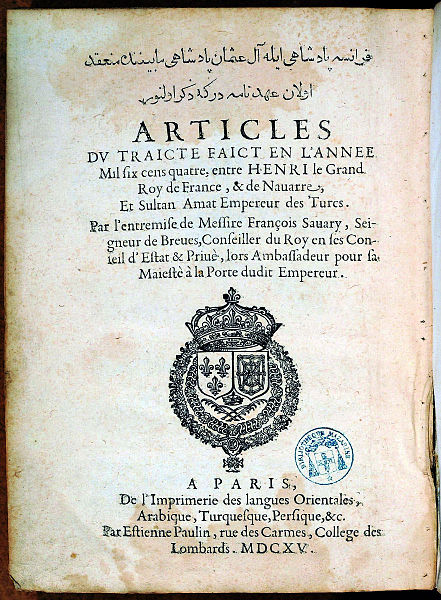

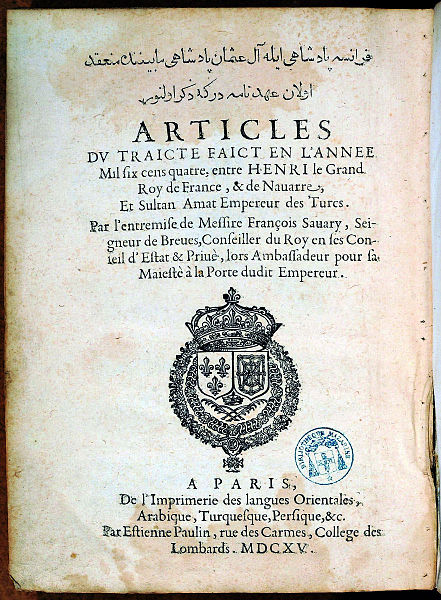

Itinerary of François Pyrard de Laval, from 1601 to 1611 During his reign, Henry IV worked through his faithful right-hand man, the minister Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, to regularize state finance, promote agriculture, drain swamps, undertake public works, and encourage education, as with the creation of the Collège Royal Henri-le-Grand in La Flèche (today the Prytanée Militaire de la Flèche). He and Sully protected forests from further devastation, built a new system of tree-lined highways, and constructed new bridges and canals. He had a 1200 metre canal built in the park at the Château Fontainebleau (which may be fished today) and ordered the planting of pines, elms, and fruit trees. The king restored Paris as a great city, with the Pont Neuf, which still stands today, constructed over the Seine river to connect the Rightand Left Banks of the city. Henry IV also had the Place Royale built (since 1800 known as Place des Vosges), and added the Grande Galerie to the Louvre Palace. More than 400 metres long and thirty-five metres wide, this huge addition was built along the bank of the Seine River, and at the time was the longest edifice of its kind in the world. King Henry IV, a promoter of the arts by all classes of people, invited hundreds of artists and craftsmen to live and work on the building's lower floors. This tradition continued for another two hundred years, until Emperor Napoleon I banned it. The art and architecture of his reign have become known as the "Henry IV style" since that time. King Henry's vision extended beyond France, and he financed several expeditions of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts, and Samuel de Champlain to North America that saw France lay claim to Canada.[25] International relations under Henry IV Coin of Henry IV, demi écu, Saint Lô, 1589 The reign of Henry IV saw the continuation of the rivalry among France, the Habsburg rulers of Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire for the mastery of Western Europe, a conflict that would only be resolved after the end of the Thirty Years' War. Spain and Italy[edit] During Henry's struggle for the crown, Spain had been the principal backer of the Catholic League, and it tried to thwart Henry. UnderAlexander Farnese, Duke of Parma an army from the Spanish Netherlands intervened in 1590 against Henry and foiled his siege of Paris. Another Spanish army helped the nobles opposing Henry to win the Battle of Craon against his troops in 1592. After Henry's coronation, the war continued as an official tug-of-war between the French and Spanish states that was terminated by the Peace of Vervins in 1598. This enabled Henry to turn his attention to Savoy, with which he also had been fighting. Their conflicts were settled in the Treaty of Lyon of 1601, which mandated territorial exchanges between France and the Duchy of Savoy. On April 1610 his liutenant Les Diguieres sign an alliance with Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy against Spain: the Treaty of Bruzolo, upside down after Henry's death[26] by Marie de' Medici just crowned queen, with rapprochement to Spain.[27] Germany[edit] In 1609 Henry's intervention helped to settle the War of the Jülich succession through diplomatic means. It was widely believed that in 1610 Henry was preparing to go to war against the Holy Roman Empire. The preparations were terminated by his assassination, however, and the subsequent rapprochement with Spain under the regency of Marie de' Medici. Ottoman Empire Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese Moriscos in plans against the Habsburg government of Spain in the 1570s.[29] Around 1575, plans were made for a combined attack of Aragonese Moriscos and Huguenots from Béarn under Henry against Spanish Aragon, in agreement with the king of Algiers and the Ottoman Empire, but these projects floundered with the arrival of John of Austria in Aragon and the disarmament of the Moriscos.[30][31] In 1576, a three-pronged fleet from Constantinople was planned to disembark between Murcia and Valencia while the French Huguenots would invade from the north and the Moriscos accomplish their uprising, but the Ottoman fleet failed to arrive.[30] After his crowning, Henry continued the policy of a Franco-Ottoman alliance and received an embassy from Sultan Mehmed III in 1601.[32][33] In 1604, a "Peace Treaty and Capitulation" was signed between Henry IV and the Ottoman Sultan Ahmet I. It granted numerous advantages to France in the Ottoman Empire In 1606–7, Henry IV sent Arnoult de Lisle as Ambassador to Morocco in order to obtain the observance of past friendship treaties. An embassy was sent to Tunisia in 1608 led by François Savary de Brèves. | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment