|

|

|

|

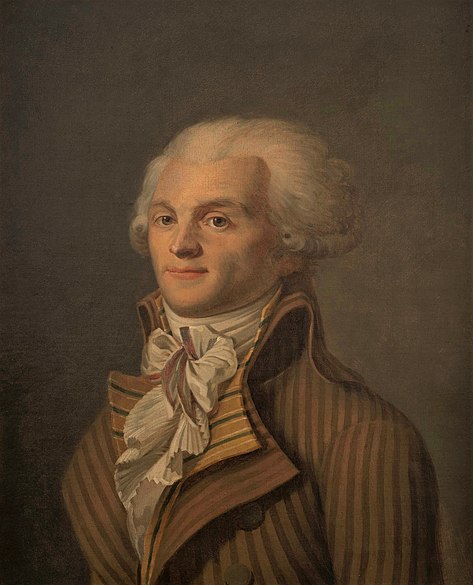

| Maximilien de Robespierre AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONMaximilien Robespierre

Robespierre c. 1790, Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer, politician, and one of the best-known and most influential figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Estates-General, the Constituent Assembly and the Jacobin Club, he advocated against the death penalty and for the abolition of slavery, while supporting equality of rights, universal suffrage and the establishment of a republic. He opposed war with Austria and the possibility of a coup by La Fayette. As a member of the Committee of Public Safety, he was an important figure during the period of the Revolution commonly known as the Reign of Terror, which ended a few months after his arrest and execution in July 1794. Influenced by 18th-century Enlightenment philosophes such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Montesquieu, he was a capable articulator of the beliefs of the left-wingbourgeoisie. He was described as being physically unimposing and immaculate in attire and personal manners. His supporters called him "The Incorruptible", while his adversaries called him dictateur sanguinaire Early life Maximilien de Robespierre was born in Arras, in the old province of Artois, France. His family has been traced back to the 12th century in Picardy; some of his direct ancestors in the male line were notaries in the village of Carvin near Arras from the beginning of the 17th century. He is sometimes rumoured to have been of Irish descent, and it has been suggested that his surname could be a corruption of "Robert Speirs". George Henry Lewes, Ernest Hamel, Jules Michelet, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Hilaire Belloc have all cited this theory although there appears to be little supporting evidence. His paternal grandfather, Maximilien de Robespierre, established himself in Arras as a lawyer. His father, Maximilien Barthélémy François de Robespierre, also a lawyer at the Conseil d'Artois, married Jacqueline Marguerite Carrault, the daughter of a brewer, in 1758. Maximilien was the oldest of four children and was conceived out of wedlock; his siblings were Charlotte, Henriette, and Augustin. In 1764, Madame de Robespierre died in childbirth. Her husband subsequently left Arras and traveled throughout Europe, only occasionally living in Arras, until his death in Munich in 1777; the children were brought up by their maternal grandfather and aunts. Maximilien attended the collège (middle school) of Arras when he was eight years old, already knowing how to read and write. In October 1769, on the recommendation of the bishop, he obtained a scholarship at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. Robespierre studied at Louis-le-Grand until age twenty-three, where he also received his training as a lawyer. Upon his graduation, he received a 600-livre special prize for twelve years of exemplary academic success and personal good conduct. Here he learned to admire the idealised Roman Republic and the rhetoric of Cicero, Cato and other classic figures. His fellow pupils included Camille Desmoulins andStanislas Fréron. He also was exposed to Rousseau during this time and adopted many of the same principles. Robespierre became more intrigued by the idea of a virtuous self, a man who stands alone accompanied only by his conscience. Shortly after his coronation, King Louis XVI visited Louis-le-Grand. Robespierre, then 17 years old and a prize-winning student, had been chosen out of five hundred pupils to deliver a speech to welcome the king. Perhaps due to rain, the royal couple remained in their coach throughout the ceremony and promptly left at its completion. Early politics As an adult, and possibly even as a young man, the greatest influence on Robespierre's political ideas was Jean Jacques Rousseau. Robespierre's conception of revolutionary virtue and his program for constructing political sovereignty out of direct democracy came from Rousseau; and, in pursuit of these ideals, he eventually became known during the Jacobin Republic as "the Incorruptible". Robespierre believed that the people of France were fundamentally good and were therefore capable of advancing the public well-being of the nation. After having completed his law studies, Robespierre was admitted to the Arras bar. The Bishop of Arras, Louis François Marc Hilaire de Conzié, appointed him criminal judge in the Diocese of Arras in March 1782. Although this appointment did not prevent him from practicing at the bar, he soon resigned owing to discomfort in ruling on capital cases arising from his early opposition to the death penalty.[6] He quickly became a successful advocate and chose, in principle, to represent the poor. During court hearings, he was known often to advocate the ideals of the Enlightenment and argue for the rights of man.[9] Later in his career, he read widely, and also became interested in society in general. He became regarded as one of the best writers and most popular young men of Arras. In December 1783, he was elected a member of the academy of Arras, the meetings of which he attended regularly. In 1784, he obtained a medal from the academy of Metz for his essay on the question of whether the relatives of a condemned criminal should share his disgrace. He and Pierre Louis de Lacretelle, an advocate and journalist in Paris, divided the prize. Many of his subsequent essays were less successful; but, Robespierre was compensated for these failures by his popularity in the literary and musical society at Arras, known as the "Rosatia", of which Lazare Carnot, who would be his colleague on theCommittee of Public Safety, was also a member. In 1788, he took part in a discussion of how the French provincial government should be elected, arguing in his Addresse à la nation artésienne that if the former mode of election by the members of the provincial estates were again adopted, the new Estates-General would not represent the people of France. It is possible he addressed this issue so that he could have a chance to take part in the proceedings and thus change the policies of the monarchy. King Louis XVI later announced new elections for all provinces, thus allowing Robespierre to run for the position of deputy for the Third Estate.

Although the leading members of the corporation were elected, Robespierre, their chief opponent, succeeded in getting elected with them. In the assembly of thebailliage, rivalry ran still higher; but, Robespierre had begun to make his mark in politics with the Avis aux habitants de la campagne (Arras, 1789). With this, he secured the support of the country electors; and, although only thirty, comparatively poor, and lacking patronage, he was elected fifth deputy of the Third Estate ofArtois to the Estates-General. When Robespierre arrived at Versailles, he was relatively unknown; but, he soon became part of the representative National Assembly which then transformed into the Constituent Assembly.[6] While the Constituent Assembly occupied itself with drawing up a constitution, Robespierre turned from the assembly of provincial lawyers and wealthy bourgeois to the people of Paris. He was a frequent speaker in the Constituent Assembly, voicing many ideas for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Constitutional Provisions, often with great success.[6] He was eventually recognized as second only to Pétion de Villeneuve – if second he was – as a leader of the small body of the extreme left; "the thirty voices" as Mirabeau contemptuously called them. [edit]Jacobin ClubRobespierre soon became involved with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, known eventually as the Jacobin Club. This had consisted originally of the deputies from Brittany only. After the Assembly moved to Paris, the Club began to admit various leaders of the Parisian bourgeoisie to its membership. As time went on, many of the more intelligent artisans and small shopkeepers became members of the club. Among such men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. As the wealthier bourgeois of Paris and right-wing deputies seceded from the club of 1789, the influence of the old leaders of the Jacobins, such as Barnave, Duport, Alexandre de Lameth, diminished. When they, alarmed at the progress of the Revolution, founded the club of the Feuillants in 1791, the left, including Robespierre and his friends, dominated the Jacobin Club. On 15 May 1791, Robespierre proposed and carried the motion that no deputy who sat in the Constituent could sit in the succeeding Assembly. The flight on 20 June, and subsequent arrest at Varennes of Louis XVI and his family resulted in Robespierre declaring himself at the Jacobin Club to be "ni monarchiste ni républicain" ("neither monarchist nor republican"). But this stance was not unusual; very few at this point were avowed republicans. After the massacre on the Champ de Mars on 17 July 1791, in order to be nearer to the Assembly and the Jacobins, he moved to live in the house of Maurice Duplay, a cabinetmaker residing in the Rue Saint-Honoré and an ardent admirer of Robespierre. Robespierre lived there (with two short intervals excepted) until his death. In fact, according to his doctor, Souberbielle, Vilate, a juror on the Revolutionary Tribunal, and his host's youngest daughter (who would later marry Philippe Le Bas of the Committee of General Security), he became engaged to the eldest daughter of his host, Éléonore Duplay.[10] On 30 September, on the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, the people of Paris named Pétion and Robespierre as the two incorruptible patriots in an attempt to honor their purity of principles, their modest ways of living, and their refusal of bribes and offers.[9] With the dissolution of the Assembly, he returned to Arras for a short visit, where he met with a triumphant reception. In November, he returned to Paris to take the position of public prosecutor of Paris.[11] Opposition to war with AustriaTerracotta bust of Robespierre by Deseine, 1792 (Château de Vizille) In February 1792, Jacques Pierre Brissot, one of the leaders of the Girondist party in the Legislative Assembly, urged that France should declare war against Austria.Marat and Robespierre opposed him, because they feared the influence of militarism, which might be turned to the advantage of the reactionary forces. Robespierre was also convinced that the internal stability of the country was more important; this opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondists, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. Robespierre countered, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Indeed, argued Robespierre, such a war could only favor the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear, for in wartime the powers of the generals would grow at the expense of ordinary soldiers, and the power of the king and court at the expense of the Assembly. These dangers should not be overlooked, he reminded his listeners, "...in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries."[12] Robespierre warned against the threat of dictatorship, stemming from war, in the following terms: “ Robespierre also argued that force was not an effective or proper way of spreading the ideals of the Revolution: “ — Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[14] In April 1792, Robespierre resigned the post of public prosecutor of Versailles, which he had officially held, but never practiced, since February, and started a journal,Le Défenseur de la Constitution. The journal served multiple purposes: countering the influence of the royal court in public policy, defending Robespierre from the accusations of Girondist leaders, and also giving voice to the economic interests of the broader masses in Paris and beyond.[15] [edit]The National ConventionWhen the Legislative Assembly declared war against Austria on 20 April 1792, Robespierre responded by working to reduce the political influence of the officer class, the generals and the king. While arguing for the welfare of common soldiers, Robespierre urged new promotions to mitigate domination of the officer class by the aristocratic École Militaire; along with other Jacobins he also urged the creation of popularmilitias to defend France.[16] This sentiment reflected the perspective of more radical Jacobins including those of the Marseille Club, who in May and June 1792 wrote to Pétion and the people of Paris, "Here and at Toulon we have debated the possibility of forming a column of 100,000 men to sweep away our enemies... Paris may have need of help. Call on us!"[17] Because French forces had suffered disastrous defeats and a series of defections at the onset of the war, Robespierre and Danton feared the possibility of a military coup d'état[18] above all led by the Marquis de Lafayette, who in June advocated the suppression of the Jacobin Club. Robespierre publicly attacked him in scathing terms: "General, while from the midst of your camp you declared war upon me, which you had thus far spared for the enemies of our state, while you denounced me as an enemy of liberty to the army, national guard and Nation in letters published by your purchased papers, I had thought myself only disputing with a general... but not yet the dictator of France, arbitrator of the state."[19] In early June Robespierre proposed an end to the Monarchy and the subordination of the Assembly to the popular will.[20] Following the King's veto of the Legislative Assembly's efforts to raise a militia and suppress non-juring priests, the Monarchy faced an abortive insurrection on 20 June, exactly three years after the Tennis Court Oath.[21] Insurrectionary forces entered Paris without the King's approval, and on 10 August 1792, these insurrectionary militias led a successful assault upon the Tuileries Palace with the intention of overthrowing the Monarchy.[22] On 16 August, Robespierre presented the petition of the Commune to the Legislative Assembly, demanding the establishment of a revolutionary tribunal and the summoning of a Convention chosen by universal suffrage.[23] Dismissed from his command of the French Northern Army, Lafayette fled France along with other sympathetic officers. The interrogation of Louis XVI at theNational Convention. In September, Robespierre was elected first deputy for Paris to the National Convention. Robespierre and his allies took the benches high at the back of the hall, giving them the label 'the Montagnards', or 'the Mountain'; below them were the 'Manège' of the Girondists and then 'the Plain' of the independents. The Girondists at the Convention accused Robespierre of failing to stop the September Massacres. On 26 September, the Girondist Marc-David Lasource accused Robespierre of wanting to form a dictatorship. Rumours spread that Robespierre, Marat and Danton were plotting to establish a triumvirate. On 29 October, Louvet de Couvraiattacked Robespierre in a speech, possibly written by Madame Roland. On 5 November, Robespierre defended himself, the Jacobin Club and his supporters in and beyond Paris. “ — Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[24] Turning the accusations upon his accusers, Robespierre delivered one of the most famous lines of the French Revolution to the Assembly: “ — Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[25] Robespierre's speech marked a profound political break between the Montagnards and the Girondins, strengthening the former in the context of an increasingly revolutionary situation punctuated by the fall of Louis XVI, the invasion of France and the September Massacres in Paris.[26] It also heralded increased involvement and intervention by the sans-culottes in revolutionary politics.[27] [edit]Execution of Louis XVIThe Convention's unanimous declaration of a French Republic on 21 September 1792 left open the fate of the King; a commission was therefore established to examine evidence against him while the Convention's Legislation Committee considered legal aspects of any future trial. Most Montagnards favored judgment and execution, while the Girondins were divided concerning Louis' fate, with some arguing for royal inviolability, others for clemency, and some advocating lesser punishment or death.[28] On 20 November, opinion turned sharply against Louis following the discovery of a secret cache of 726 documentsconsisting of Louis' personal communications.[29] Robespierre had taken ill in November and had done little other than support Saint-Just in his argument against the King's inviolability; Robespierre wrote in his Defenseur de la Constitution that a Constitution which Louis had violated himself, and which declared his inviolability, could not now be used in his defense.[30] Now, with the question of the King's fate occupying public discourse, Robespierre on 3 December delivered a speech that would define the rhetoric and course of Louis' trial.[31] Robespierre argued that the King, now dethroned, could function only as a threat to liberty and national peace, and that the members of the Assembly were not fair judges, but rather statesmen with responsibility for public safety: “ — Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[32] In arguing for a judgment by the elected Convention without trial, Robespierre supported the recommendations of Jean-Baptiste Mailhe, who headed the commission reporting on legal aspects of Louis' trial or judgment. Unlike some Girondins, Robespierre would specifically oppose judgment by primary assemblies or a referendum, believing that this could cause civil war.[33] While he called for a trial of queen Marie Antoinette and the imprisonment of the Dauphin, Robespierre argued for the death penalty in the case of the king: “ — Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[34] On 15 January 1793, Louis XVI was voted guilty of conspiracy and attacks upon public safety by 691 of 749 deputies; none voted for his innocence. Four days later, 387 deputies voted for death as penalty, 334 voted for detention or a conditional death penalty, and 28 abstained or were absent. Louis was executed two days later in the Place de la Révolution. [edit]Destruction of the GirondistsAfter the King's execution, the influence of Robespierre, Danton and the pragmatic politicians increased at the expense of the Girondists. The Girondists refused to have anything more to do with Danton and because of this the government became more divided. In May 1793, Desmoulins, at the behest of Robespierre and Danton, published his Histoire des Brissotins, an elaboration on the earlier article Jean-Pierre Brissot, démasqué, a scathing attack on Brissot and the Girondists. Maximin Isnard declared that Paris must be destroyed if it came out against the provincial deputies. Robespierre preached a moral "insurrection against the corrupt deputies" at the Jacobin Club. On 2 June, a large crowd of armed men from the Commune of Paris came to the Convention and arrested thirty-two deputies on charges of counter-revolutionary activities. Reign of TerrorMain article: Reign of Terror "To punish the oppressors of humanity is clemency; to forgive them is barbarity." — Maximilien Robespierre, 1794 Cartoon showing Robespierre guillotining the executioner after having guillotined everyone else in France. After the fall of the monarchy, France faced troubles as the war and the civil war continued. A stable government was needed to quell the chaos.[9] On 11 March 1793, a Revolutionary Tribunal was established by Jacobins in the Convention.[36] On 6 April, the nine-memberCommittee of Public Safety replaced the larger Committee of General Defense. On 27 July 1793, Robespierre was elected to the Committee, although he had not sought the position.[37] The Committee of General Security began to manage the country's internal police. Terror was formally instituted as a legal policy by the Convention on 5 September 1793, in a proclamation which read, "It is time that equality bore its scythe above all heads. It is time to horrify all the conspirators. So legislators, place Terror on the order of the day! Let us be in revolution, because everywhere counter-revolution is being woven by our enemies. The blade of the law should hover over all the guilty."[37] Though nominally all members of the committee were equal, Robespierre was presented during the Thermidorian Reaction by the surviving protagonists of the Terror, especiallyBertrand Barère, as prominent. They may have exaggerated his role to downplay their own contribution and used him as a scapegoat after his death.[38] As an orator, he praised revolutionary government and argued that "terror" - at least as he defined it - was necessary, laudable and inevitable. It was Robespierre's belief that the Republic and virtue were of necessity inseparable. He reasoned that the Republic could be saved only by the virtue of its citizens, and that a Robespierrist Terror was virtuous because it attempted to maintain the Revolution and the Republic. For example, in his Report on the Principles of Political Morality, given on 5 February 1794, Robespierre stated:

Robespierre’s speeches were exceptional, and he had the power to change the views of almost any audience. His speaking techniques included invocation of virtue and morals, and quite often the use of rhetorical questions in order to identify with the audience. He would gesticulate and use ideas and personal experiences in life to keep listeners' attentions. His final method was to state that he was always prepared to die in order to save the Revolution.[40] Robespierre believed that the Terror was a time of discovering and revealing the enemy within Paris, within France, the enemy that hid in the safety of apparent patriotism.[41]Because he believed that the Revolution was still in progress, and in danger of being sabotaged, he made every attempt to instill in the populace and Convention the urgency of carrying out the Terror. Robespierre saw no room for mercy in his Terror, stating that "slowness of judgments is equal to impunity" and "uncertainty of punishment encourages all the guilty". Throughout his Report on the Principles of Political Morality, Robespierre assailed any stalling of action in defense of the Republic. In his thinking, there was not enough that could be done fast enough in defence against enemies at home and abroad. A staunch believer in the teachings of Rousseau, Robespierre believed that it was his duty as a public servant to push the Revolution forward, and that the only rational way to do that was to defend it on all fronts. The Report did not merely call for blood but also expounded many of the original ideas of the 1789 Revolution, such as political equality, suffrage and abolition of privileges.[citation needed] In the winter of 1793–94, a majority of the Committee decided that the Hébertist party would have to perish or its opposition within the Committee would overshadow the other factions due to its influence in the Commune of Paris. Robespierre also had personal reasons for disliking the Hébertists for their "atheism" and "bloodthirstiness", which he associated with the old aristocracy.[11] "On the 4th of February 1794 under the leadership of Maxmilien Robespierre, the French Convention voted for the abolition of slavery. The Jacobins had established the idea of liberty, but it was a conception which favoured the emergent bourgeoisie, and it was this idea of liberty signifying the freedom to trade which took precedence over the ideas of equality and fraternity. It was this corruption of the French revolution by a rapacious cabal of the French bourgeoisie that Robespierre fought so fanatically against. In fact, during the Reign of Terror, Robespierre had huge support among the poor of Paris and he is still revered by the poor of Haiti today." – Centre for Research on Globalization[42] In early 1794, he finally broke with Danton, who had angered many other members of the Committee of Public Safety with his more moderate views on the Terror, but whom Robespierre had, until this point, persisted in defending. Subsequently, he joined in attacks on the Dantonists and the Hébertists.[6] Robespierre charged his opponents with complicity with foreign powers. From 13 February to 13 March 1794, Robespierre withdrew from active business on the Committee due to illness. On 15 March, he reappeared in the Convention. Hébert and nineteen of his followers were arrested on 19 March and guillotinedon 24 March. Danton, Desmoulins and their friends were arrested on 30 March and guillotined on 5 April. Georges Couthon, his ally on the Committee, introduced and carried on 10 June the drastic Law of 22 Prairie. Under this law, the Tribunal became a simple court of condemnation without need of witnesses. Historians frequently debate the reasons behind Robespierre's support of the 22 Prarial Law; some consider it an attempt to extend his influence into a dictatorship, while others argue it was adopted to expedite the passage of the reformist, land-redistributive Laws of Ventose.[citation needed] [edit]Cult of the Supreme BeingMain article: Cult of the Supreme Being Robespierre's desire for revolutionary change was not limited to the political realm. Having denounced the excesses of dechristianization, he sought to instill a spiritual resurgence in the French nation based onDeist beliefs. Accordingly, on 7 May 1794, Robespierre supported a decree passed by the Convention that established an official religion, known historically as the Cult of the Supreme Being. The notion of the Supreme Being was based on ideas that Jean-Jacques Rousseau had outlined in The Social Contract. A nationwide "Festival of the Supreme Being" was held on 8 June (which was also the Christian holiday ofPentecost). The festivities in Paris were held in the Champ de Mars, which was renamed the Champ de la Réunion ("Field of Reunion") for that day. This was most likely in honor of the Champ de Mars Massacrewhere the Republicans first rallied against the power of the Crown.[43] Robespierre, who happened to be President of the Convention that week, walked first in the festival procession and delivered a speech in which he emphasised his concept of a Supreme Being:

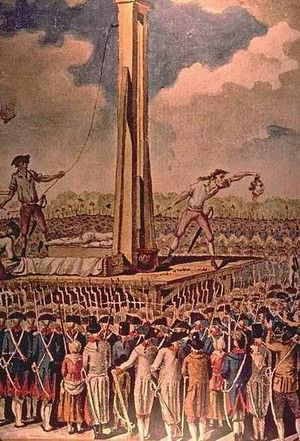

The Festival of the Supreme Being, by Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1794). Throughout the "Festival of the Supreme Being", Robespierre was beaming with joy; not even the negativity of his colleagues could disrupt his delight. He was able to speak of the things about which he was truly passionate, including Virtue and Nature, typical deist beliefs, and, of course, his disagreements with atheism. Everything was arranged to the exact specifications that had been previously set before the ceremony; the ominous and symbolic guillotine had been moved to the original standing place of the Bastille, all of the people were placed in the appropriate area designated to them, and everyone was dressed accordingly.[45] Not only was everything going smoothly, but the Festival was also Robespierre’s first appearance in the public eye as an actual leader for the people, and also as President of the Convention, to which he had been elected only four days earlier.[45] While for some it was an excitement to see him at his finest, many other leaders involved in the Festival agreed that Robespierre had taken things a bit too far. Multiple sources state that Robespierre came down the mountain in a way that resembled Moses as the leader of the people[citation needed], and one of his colleagues, Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, was heard saying, "Look at the bugger; it’s not enough for him to be master, he has to be God". While these words may have been a simple release of resentment at the time, this same idea would come back in an attempt to remove Robespierre from his lofty position in the very near future. Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier was not one of Robespierre’s devotees, and was actually attempting to find something that Robespierre had done wrong. Vadier was on a mission to attack Robespierre and his faith, and was also trying to bring down Robespierre’s political stature as well. This is when he found Catherine Théot, who was a seventy-eight-year old, self-declared "prophetess" who had, at one point, been imprisoned in the Bastille.[46] By stating that Robespierre was the "herald of the Last Days, prophet of the New Dawn",[47] (because his festival had fallen on the Pentecost, traditionally a day revealing "divine manifestation"), Catherine Théot made it seem that Robespierre had made these claims himself, to her. Many of her followers were also supporters or friends of Robespierre, which made it seem as if he were attempting to create a new religion, with himself as its god. Although Robespierre had nothing to do with Catherine Théot or her followers, many assumed that he was on a path to dictatorship, and it sent a current of fear throughout the Convention, contributing to his downfall the following July. [edit]DownfallMain article: Thermidorian Reaction Gendarme Merda shooting at Robespierre during the night of the 9 Thermidor. The execution of Robespierre. N.B.: The beheaded man is not Robespierre, but Couthon; Robespierre is shown sitting on the cart closest to the scaffold, holding a handkerchief to his mouth. On 23 May, only one day after the attempted assassination of Collot d'Herbois, Robespierre's life was also in danger: as a young woman by the name of Cécile Renault was arrested after having approached his place of residence with two small knives; she was executed one month later. At this point, the decree of 22 Prairial (also known as law of 22 Prairial) was introduced to the public without the consultation from the Committee of General Security, which, in turn, doubled the number of executions permitted by the Committee of Public Safety.[48] This law permitted executions to be carried out even under simple suspicion of citizens thought to be counter-revolutionaries without extensive trials. When Robespierre allowed this law to be passed, the people of France began to question him and the Committee because they were executing people for seemingly meaningless reasons, and also because they had passed a law without the help of the Committee of General Security. This was part of the beginning of Robespierre's downfall.[49] Reports were coming into Paris about excesses committed by the envoys sent en-mission to the provinces, particularly Jean-Lambert Tallien in Bordeaux andJoseph Fouché in Lyons. Robespierre tirelessly worked almost alone - having been opposed by other leading political figures and accused of being a counterrevolutionary for his relative moderation - to curb their excesses, having them recalled to Paris to account for their actions and then expelling them from the Jacobin Club. They, however, evaded arrest. Fouché spent the evenings moving house to house, warning members of the Convention that Robespierre was after them, whilst organising a coup d'état.[50] Robespierre appeared at the Convention on 26 July (8th Thermidor, year II, according to the Revolutionary calendar), and delivered a two-hour-long speech. He defended himself against charges of dictatorship and tyranny, and then proceeded to warn of a conspiracy against the Republic. Specifically, he railed against the bloody excesses he had observed during the Terror. He also implied that members of the Convention were a part of this conspiracy, though when pressed he refused to provide any names. The speech, however, alarmed members, particularly given Fouché's warnings. These members who felt that Robespierre was alluding to them tried to prevent the speech from being printed, and a bitter debate ensued until Barère forced an end to it. Later that evening, Robespierre delivered the same speech again at the Jacobin Club, where it was very well received.[51] The following day, Saint-Just began to give a speech in support of Robespierre. However, those who had seen him working on his speech the night before expected accusations to arise from it. Saint-Just had time to give only a small part of his speech before Jean-Lambert Tallien interrupted him. While the accusations began to pile up, Saint-Just remained uncharacteristically silent. Robespierre then attempted to secure the tribunal to speak, but his voice was shouted down. Robespierre soon found himself at a loss for words after one deputy called for his arrest; another deputy, Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier, gave a mocking impression of him. When one deputy realised Robespierre's inability to respond, the man shouted, "The blood of Danton chokes him!".[52] Robespierre then finally regained his voice to reply with his one recorded statement of the morning, demanding to know why, when he had been the only one left protecting Danton in the end, he was now being blamed for the other man's death: "Is it Danton you regret? ... Cowards! Why didn't you defend him?"[citation needed] [edit]ArrestThe Convention ordered the arrest of Robespierre, his brother Augustin, Couthon, Saint-Just, François Hanriot, and Le Bas. Troops from the Commune, under General Coffinhal, arrived to free the prisoners and then marched against the Convention itself. The Convention responded by ordering troops of its own underBarras to be called out. When the Commune's troops heard the news of this, order began to break down, and Hanriot ordered his remaining troops to withdraw to the Hôtel de Ville, where Robespierre and his supporters also gathered. The Convention declared them to be outlaws, meaning that upon verification the fugitives could be executed within twenty-four hours without a trial. As the night went on, the forces of the Commune deserted the Hôtel de Ville and, at around two in the morning, those of the Convention under the command of Barras arrived there. In order to avoid capture, Augustin Robespierre threw himself out of a window, only to break both of his legs; Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase; Le Bas committed suicide; and another radical shot himself in the head. Robespierre tried to kill himself with a pistol but managed only to shatter his lower jaw,[53] although some eye-witnesses[54] claimed that Robespierre was shot by Charles-André Merda. ExecutionFor the remainder of the night, Robespierre was moved to a table in the room of the Committee of Public Safety where he awaited execution. He lay on the table bleeding abundantly until a doctor was brought in to attempt to stop the bleeding from his jaw. Robespierre's last recorded words may have been "Merci, monsieur," to a man that had given him a handkerchief for the blood on his face and clothing.[55] Later, Robespierre was held in the same containment chamber where Marie Antoinette, the wife of King Louis XVI, had been held. The next day, 28 July 1794, Robespierre was guillotined without trial in the Place de la Révolution. His brother Augustin, Couthon, Saint-Just, Hanriot, and twelve other followers, among them the cobbler Antoine Simon, the jailor of Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France, were also executed. When clearing Robespierre's neck, the executioner tore off the bandage that was holding his shattered jaw in place, causing Robespierre to produce an agonised scream until the fall of the blade silenced him.[56] Together with those executed with him, he was buried in a common grave at the newly opened Errancis Cemetery(cimetière des Errancis) (March 1794 – April 1797)[57] (near what is now the Place Prosper-Goubaux). A plaque indicating the former site of the cimetière des Errancis is located at 97 rue de Monceau, Paris 75008. Between 1844 and 1859 (probably in 1848), the remains of all those buried there were moved to the Catacombs of Paris. [edit]LegacyMaximilien Robespierre remains a controversial figure to this day. Apart from one Metro station in Paris, there are no memorials or monuments to him in France. By making himself the embodiment of virtue and of total commitment, he took control of the Revolution in its most radical and bloody phase – the Jacobin republic. His goal in the Terror was to use the guillotine to create what he called a 'republic of virtue', wherein terror and virtue, his principles, would be imposed. He argued, "Terror is nothing more than speedy, severe and inflexible justice; it is thus an emanation of virtue; it is less a principle in itself, than a consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing needs of the patrie."[58] Terror was thus a tool to accomplish his overarching goals for democracy. Historian Ruth Scurr wrote that as for Robespierre's vision for France he wanted a "democracy for the people, who are intrinsically good and pure of heart; a democracy in which poverty is honorable, power innocuous, and the vulnerable safe from oppression; a democracy that worships nature—not nature as it really is, cruel and disgusting, but nature sanitized, majestic, and, above all, good."[59] In terms of historiography, he has several defenders. Marxist historian Albert Soboul viewed most of the measures of the Committee for Public Safety necessary for the defense of the Revolution and mainly regretted the destruction of the Hébertists and other enragés.

He was a bourgeois; Albert Soboul, according to Ishay, argues that he and Saint-Just "were too preoccupied in defeating the interest of the bourgeoisie to give their total support to the sans-culottes, and yet too attentive to the needs of the sans-culottes to get support from the middle class."[60] For Marxists like Soboul Robespierre's petit-bourgeois class interests were fatal to his mission.[61] The 1902 Encyclopædia Britannica sums up Robespierre as a bright young theorist but out of his depth in the matter of experience:[62]

Romanticism originated in the second half of the 18th century at the same time as the French Revolution.[1] Romanticism continued to grow in reaction to the effects of the social transformation caused by the Revolution. There are many signs of these effects of the French Revolution in various pieces of Romantic literature. By examining the influence of the French Revolution, one can determine that Romanticism arose as a reaction to the French Revolution. Instead of searching for rules governing nature and human beings, the romantics searched for a direct communication with nature and treated humans as unique individuals not subject to scientific rules.

According to Albert Hancock, in his book The French Revolution and the English Poets: a study in historical criticism, “The French Revolution came, bringing with it the promise of a brighter day, the promise of regenerated man and regenerated earth. It was hailed with joy and acclamation by the oppressed, by the ardent lovers of humanity, by the poets, whose task it is to voice the human spirit.”[2] A common theme among some of the most widely known romantic poets is their acceptance and approval of the French Revolution. William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, and Percy Shelleyall shared the same view of the French Revolution as it being the beginning of a change in the current ways of society and helping to better the lives of the oppressed. As the French Revolution changed the lives of virtually everyone in the nation and even continent because of its drastic and immediate shift in social reformation, it greatly influenced many writers at the time. Hancock writes, “There is no need to recount here in detail how the French Revolution, at the close of the last century, was the great stimulus to the intellectual and emotional life of the civilized world, how it began by inspiring all liberty-loving men with hope and joy.”[2] Literature began to take a new turn when the spirit of the revolution caught the entire nation and turned things in a whole new direction. The newly acquired freedom of the common people did not only bring about just laws and living but ordinary people also had the freedom to think for themselves, and in turn the freedom to express themselves. Triggered by the revolutionary spirit, the writers of the time were full of creative ideas and were waiting for a chance to unleash them. Under the new laws writers and artists were given a considerable amount of freedom to express themselves which did well to pave the way to set a high standard for literature.[3] Prior to the French Revolution, poems and literature were typically written about and to aristocrats and clergy, and rarely for or about the working man. However, when the roles of society began to shift resulting from the French Revolution, and with the emergence of Romantic writers, this changed.[4] Romantic poets such as Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley started to write works for and about the working man; pieces that the common man could relate to. According to Christensen, “To get the real animating principle of the Romantic Movement, one must not study it inductively or abstractly; one must look at it historically. It must be put beside the literary standards of the eighteenth century. These standards impose limits upon the Elysian fields of poetry; poetry must be confined to the common experience of average men… The Romantic Movement then means the revolt of a group of contemporary poets who wrote, not according to common and doctrinaire standards, but as they individually pleased… there are no principles comprehensive and common to all except those of individualism and revolt.”[5] [edit]A closer look at the influence of the French Revolution on selected Romantic poetsAlthough the poets mentioned earlier (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley) all share the common theme of approving the French Revolution, they each have their own unique ideas regarding the Revolution itself that have greatly shaped their work. This can be seen by analyzing some of each of their works. [edit]ShelleyEver since he was young, Percy Shelley was very nontraditional, in fact he is said to have been opposed to tradition. He was born a freethinker and “in spite of all his lovable and generous traits he was a born disturber of the public peace”. At school he was known as “Mad Shelley, the Atheist”. According to Hancock, “The Goddess of Revolution rocked his cradle.”[2] Throughout his life Shelley’s opposition toward religion grew less violent, however he never professed a belief in immortality or religion of any sort.[6] His poems declare a belief in the permanence of things that are true and beautiful. Common themes that Shelley incorporated into his works include the hatred of kings, faith in the natural goodness of man, the belief in the corruption of present society, the power of reason, the rights of natural impulse, the desire for a revolution, and liberty, equality and fraternity.[5] These are all clearly shaped by the French Revolution. [edit]ByronWhile Shelley had faith that was founded upon modern ideas, Byron had faith in nothing. He stood for only destruction. Because of this he was not a true revolutionist and was rather “the arch-apostle of revolt, of rebellion against constituted authority.”[2] This statement is easily defended as Byron admitted that he resisted authority but offered no substitute. This is supported by what Byron once wrote, “I deny nothing… but I doubt everything.” He then said later in life, “I have simplified politics into an utter detestation of all existing governments.” [7] Byron believed neither in democracy nor in equality, but opposed all forms of tyranny and all attempts of rulers to control man. In Byron’s poetry, he incorporated deep feeling, rather than deep thinking, to make his characters strong. Often, Byron portrayed his characters as being in complete harmony with nature, causing the character to lose himself in the immensity of the world. The French Revolution played a huge role in shaping Byron’s beliefs and opposition to monarchy. [edit]WordsworthWhile Shelley and Byron both proved to support the revolution to the end, both Wordsworth and Coleridge joined the aristocrats in fighting it.[8] Wordsworth, however is the Romantic poet who has most profoundly felt and expressed the connection of the soul with nature. He saw great value in the immediate contact with nature. The French Revolution helped to humanize Wordsworth as his works transitioned from extremely natural experiences to facing the realities and ills of life, including society and the Revolution. From then on, his focus became the interests of man rather than the power and innocence of nature. ColeridgeUnlike Wordsworth, Coleridge was more open and receptive to the social and political world around him. He was a very versatile man and he led a life that covered many fields and his work displayed this.[8] He was a poet of nature, romance, and the Revolution. He was a philosopher, a historian, and a political figure.[4] The French Revolution played a great role in shaping Coleridge into each of these things. According to Albert Hancock, Coleridge tended to focus his life on two things. The first, being to separate himself from the surrounding world and to submerge himself in thought, as a poet. The second, to play a role in the world’s affairs, as a philosopher, historian, and politician, as mentioned earlier. |

The Execution of King Louis XVIThe execution of King Louis XVI under Robespierre's Reign of Terror, with the crowd looking on

guillotineA picture of the guilltoine used during Robespierre's Reign of Terror.

grave of mlle lenormandMarie Anne Adelaide Lenormand (1772 - 1843) was a French professional fortune-teller, active for more than 40 years and of considerable fame during the Napoleonic era. She claimed to have given cartomantic advice to many famous persons, among them leaders of the French revolution (Marat, Robespierre and St-Just), Empress Josephine, and Czar Alexander. In 1814 she started a second literary career and published many texts, causing many public controversies. She was imprisoned more than once, though never for very long. In France she's considered the greatest cartomancer of all time, highly influential on the wave of French cartomancy that began in the late 18th century. After her death her name was used on a newly-developed divination card deck, the so-called Lenormand cards. These are still used extensively in modern Germany, almost as popular as Tarot cards in some regions.

Monument aux GirondinsThe Girondists were originally part of France’s Legislative Assembly, becoming one of the groups which supported the French Revolution as it began. In fact, they were one of the legislature’s most militant sections.

Pont Notre-DameParis, 1998 Pont Notre-Dame, most recently rebuilt in 1913, spans the Seine in approximately the same place as the main ancient Roman bridge. The building with the conical "hats" is the infamous Conciergerie, where prisoners of the French Revolution such as Marie-Antoinette and Robespierre were kept prior to being separated from their heads.

Place de la Concorde - one of the two fountains, the Marly horses and the Grand Palais in the background |

|

Paris - Île de la Cité: Sainte-Chapelle and Palais de JusticePalais de Justice (literally Palace of Justice, but commonly translated as Hall of Justice) is built on the site of the former royal palace of Saint Louis, of which the Sainte Chapelle remains. Palais de Justice (literally Palace of Justice, but commonly translated as Hall of Justice) is built on the site of the former royal palace of Saint Louis, of which the Sainte Chapelle remains. It houses tribunal de grande instance (Paris Court of Large Claims) and the associated Paris correctional court, the Paris Court of Appeal, and the French Cour de cassation, which is the highest jurisdiction in the French judicial order. It also houses the Conciergerie, a former prison, now a museum, notable for housing many high profile sentencees, including Marie Antoinette, before being executed on the guillotine. The first Capetians, with Robert II The Pious (996-1031), had the royal palace built as a symbol of sovereignty. The king's residence is located in the eleventh chamber of the Appeal Court. After 1111, King Louis VI, called "The Fat", ordered the construction of the royal dungeon in the courtyard behind the king's residence. This dungeon is known by the name of "Grosse Tour" (it was later called the "Tour Montgomery"). Philip Augustus was born in the palace in 1165. He was christened in the Chapelle Saint-Michel. Louis IX, dubbed "Saint-Louis", lived in the king's residence. He spent his wedding night praying in the King's chamber. He undertook several additions to the building: the Sainte-Chapelle, the Trésor des Chartes, the Chambre des Plaids, the Hall on the Water and the Bonbec tower. Philip IV (1285- 1314) commissioned Enguerrand de Marigny to rebuild the palace. The wall of the Cité was moved. Several buildings that stand either outside of the walls or between the wall and the palace were expropriated. The king's residence was remodeled. The Great Hall (the lobby) also called "prosecutor's room" or "Parlement hall", is the seat of Justice where the king holds the "Beds of Justice". The walls of the palace witnessed a succession of kings up until Charles V, heir to the throne. On February 22, 1358, insurgents in Paris, under Étienne Marcel, the provost of merchants, penetrated into the chamber of the Dauphin, future King Charles V, then regent of France in the absence of his father, John The Good, who was being held captive in England. The king's counselors, Jean de Conflans and Robert Clermont, had their throats cut before the Dauphin's eyes in the Merchant's Gallery, their blood spattering onto the regent as the provost placed the hood bearing the red and blue colors of Paris on his head. When Charles V was once more in control of the situation, he moved out of the palace, which held too many unpleasant memories, and henceforward took residences in the Louvre, the Hôtel Saint-Pol or Vincennes, outside of Paris. The Parlement of Paris was the first supreme court of justice of the kingdom. Originally, the king appointed its members. But Francis I, short of money, sold the titles to replenish his resources. From then on, they were considered the property of their owners, and were passed on to the heirs. Entitled to a seat in Parlement, by right or by privilege, were the noble figures of the realm: royal princes, the peers of France. When they rose up against the Crown, refusing to transcribe the royal edicts in their records, the sovereign resorted to the Bed of Justice, a formal session held in his presence. Exile to the provinces or prison were sometimes necessary. The tribunal, created by the Convention, was allocated the most prestigious rooms in the history of the Parlement of Paris: the Great Hall and the Saint-Louis Hall, renamed "chambre de la Liberté" and "chambre de l'Égalité". Fouquier-Tinville was put in charge of drawing up the indictments. The public prosecutor had a tied apartment set up at Quai de l'Horloge, adjacent to the Bonbec Tower, where he could be closer to his victims to prepare the cases and accelerate the already precipitous proceedings. Between April 1793 and July 1794, the Revolutionary Tribunal ordered the execution by guillotine of 2,600 people. Marie-Antoinette was sentenced to die on October 16, 1793. She was guillotined on the Revolution Square. Danton was sentenced to death by the very tribunal that he helped to create. Robespierre was also sentenced to death. In 1795, the members of the tribunal and its public prosecutor, Fouquier-Tinville, were condemned by the same jurisdiction that they lead. The Revolution toppled the judicial organization. The new tribunals set up camp in the old building. Shortly after the coup, Napoleon ordered the architect Giraud to direct the indispensable repairs. Under Napoleon's reign, the judges were appointed by the government in power. In 1804, Napoleon restored the title of "court". The "tribunals of appeal" and the "supreme tribunal of appeal" became the "court of appeal" and "supreme court of appeal". These courts rendered "judgements" and their judges wore the title of "councilor". The Law Society was restored in 1810. The work undertaken under Baron Haussmann was completed, and the war of 1870 broke out. During the Commune, the insurgents set fires and on the night of May 24, 1871, the palace was set ablaze. Part of the palace was destroyed. The palace was rebuilt under the Third Republic. The Appeal Court of Paris was moved to premises built on the Quai des Orfèvres and in the courtyard of the Sainte-Chapelle. In 1875, the Harlay Hall and its staircase on the Place Dauphine was inaugurated. The premises of the judicial police and the criminal courts were completed in 1914. |

The French Revolution played a huge role in influencing Romantic writers. As the Revolution began to play out, the

The French Revolution played a huge role in influencing Romantic writers. As the Revolution began to play out, the

No comments:

Post a Comment