|

Mexican War Volunteer Scenes from a morning at Columbia State Park in the Gold Country of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. |

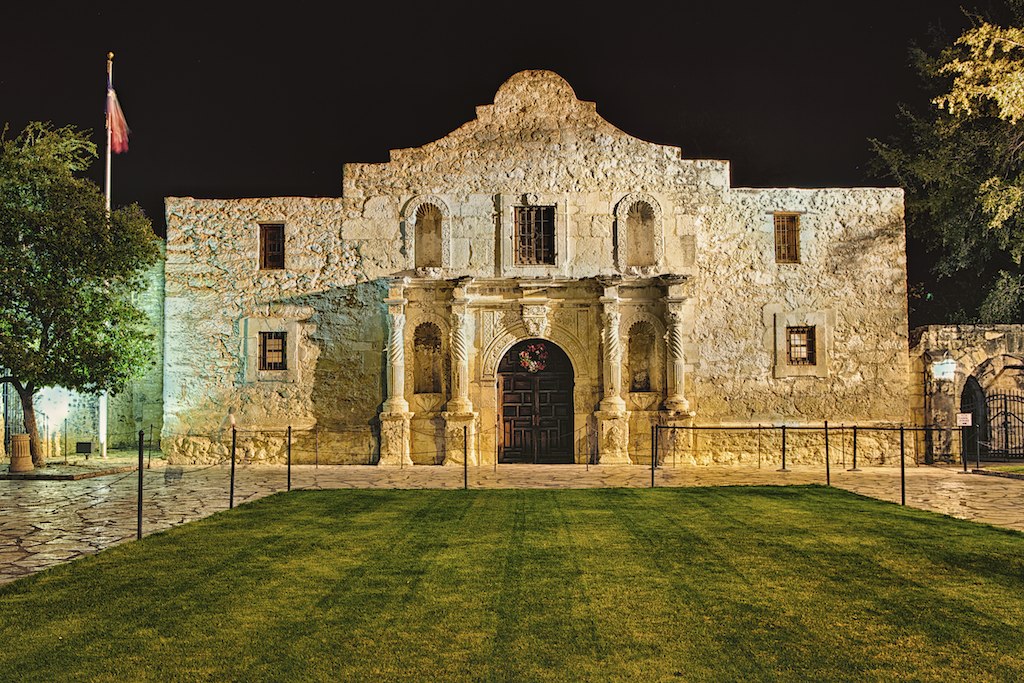

San Antonio, TX - The Alamo. The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo Mission near San Antonio de Béxar (modern-day San Antonio, Texas, USA). All but two of the Texan defenders were killed. Santa Anna's perceived cruelty during the battle inspired many Texans—both Texas settlers and adventurers from the United States—to join the Texan Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texans defeated the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, on April 21, 1836, ending the revolution. |

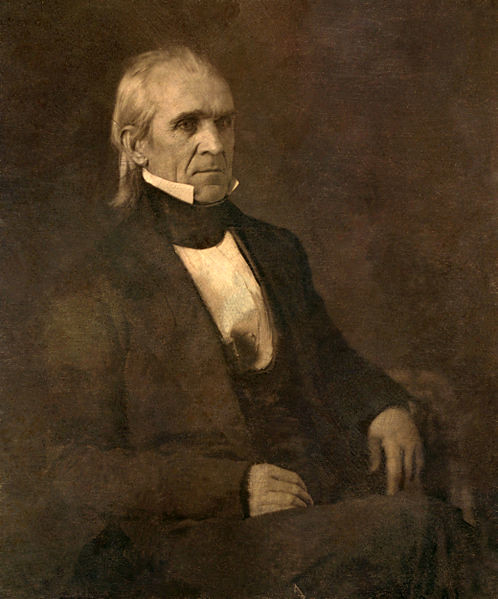

The Annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo,1845-1848During his tenure, U.S. President James K. Polk oversaw the greatest territorial expansion of the United States to date. Polk accomplished this through the annexation of Texas in 1845, the negotiation of the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain in 1846, and the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848, which ended with the signing and ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848.

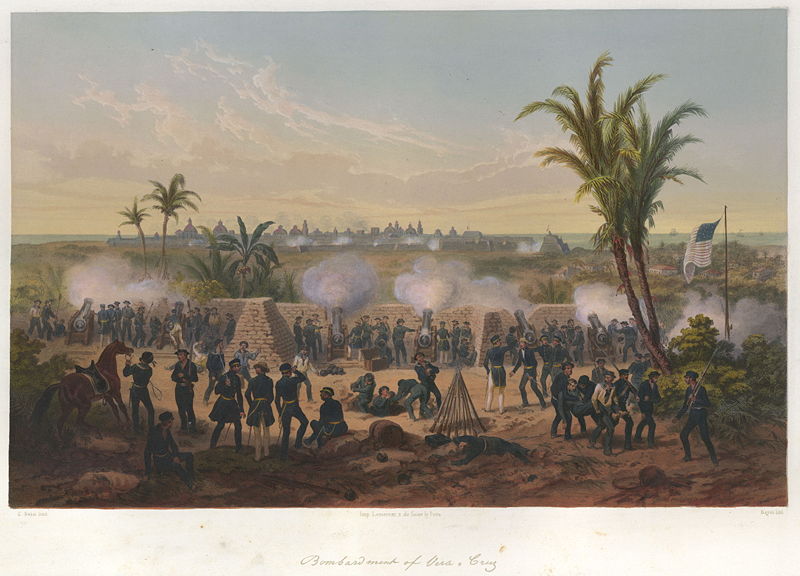

The Battle of Veracruz These events brought within the control of the United States the future states of Texas, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Washington, and Oregon, as well as portions of what would later become Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana. Following Texas’ successful war of independence against Mexico in 1836, President Martin van Burenrefrained from annexing Texas after the Mexicans threatened war. Accordingly, while the United States extended diplomatic recognition to Texas, it took no further action concerning annexation until 1844, when President John Tyler restarted negotiations with the Republic of Texas. His efforts culminated on April 12 in a Treaty of Annexation, an event that caused Mexico to sever diplomatic relations with United States. Tyler, however, lacked the votes in the Senate to ratify the treaty, and it was defeated by a wide margin in June. Shortly before he left office, Tyler tried again, this time through a joint resolution of both houses of Congress. With the support of President-elect Polk, Tyler managed to get the joint resolution passed on March 1, 1845, and Texas was admitted into the United States on December 29.

President John Tyler While Mexico did not follow through with its threat to declare war if the United States annexed Texas, relations between the two nations remained tense due to Mexico’s disputed border with Texas. According to the Texans, their state included significant portions of what is today New Mexico and Colorado, and the western and southern portions of Texas itself, which they claimed extended to the Rio Grande River. The Mexicans, however, argued that the border only extended to the Nueces River, several miles to the north of the Rio Grande. In July, 1845, Polk, who had been elected on a platform of expansionism, ordered the commander of the U.S. Army in Texas, Zachary Taylor, to move his forces into the disputed lands that lay between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers. In November, Polk dispatched Congressman John Slidell to Mexico with instructions to negotiate the purchase of the disputed areas along the Texas-Mexican border, and the territory comprising the present-day states of New Mexico and California. Following the failure of Slidell’s mission in May 1846, Polk used news of skirmishes between Mexican troops and Taylor’s army to gain Congressional support for a declaration of war against Mexico. The President neglected to inform Congress, however, that the Mexicans had used force only after Taylor’s troops had positioned themselves on the banks of the Rio Grande River, which was effectively Mexican territory. On May 13, 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Following the capture of Mexico City in September 1847, Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the Department of State and Polk's peace emissary, began negotiations for a peace treaty with the Mexican Government under terms similar to those pursued by Slidell the previous year. Polk soon grew concerned by Trist’s conduct, however, believing that he would not press for strong enough terms from the Mexicans, and because Trist became a close friend of General Winfield Scott, a Whig who was thought to be a strong contender for his party’s presidential nomination for the 1848 election. Furthermore, the war had encouraged expansionist Democrats to call for a complete annexation of Mexico. Polk recalled Trist in October.

Chief Clerk of the Department of State, Nicholas Trist Believing that he was on the cusp of an agreement with the Mexicans, Trist ignored the recall order and presented Polk with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which was signed in Mexico City on February 2, 1848. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded to the United States approximately 525,000 square miles (55% of its prewar territory) in exchange for a $15 million lump sum payment, and the assumption by the U.S. Government of up to $3.25 million worth of debts owed by Mexico to U.S. citizens. While Polk would have preferred a more extensive annexation of Mexican territory, he realized that prolonging the war would have disastrous political consequences and decided to submit the treaty to the Senate for ratification. Although there was substantial opposition to the treaty within the Senate, on March 10, 1848, it passed by a razor-thin margin of 38 to 14. The war had another significant outcome. On August 8, 1846, Congressman David Wilmot introduced a rider to an appropriations bill that stipulated that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist” in any territory acquired by the United States in the war against Mexico. While Southern senators managed to block adoption of the so-called “Wilmot Proviso,” it nonetheless provoked a political firestorm. The question of whether slavery could expand throughout the United States continue to fester until the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865.

Alamo, San AntonioSan Antonio Texas River Walk Alamo

James PolkJames Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th President of the United States (1845–1849). Polk is now recognized, not only as the strongest president between Jackson and Lincoln, but the president who made the United States a coast-to-coast nation. James Knox Polk, the first of ten children, was born on November 2, 1795 in a farmhouse (possibly a "log" cabin) in what is now Pineville, North Carolina in Mecklenburg County, just outside Charlotte. His father, Samuel Polk, was a slaveholder, successful farmer and surveyor of Scots-Irish descent. His mother, Jane Polk (née Knox), was a descendant of a brother of the Scottish religious reformer John Knox. She named her firstborn after her father James Knox. Like most early Scots-Irish settlers in the North Carolina mountains, the Knox and Polk families were Presbyterian. While Jane remained a devout Presbyterian her entire life, Samuel (whose father, Ezekiel Polk, was a deist) rejected dogmatic Presbyterianism. When the parents took James to church to be baptized, the father Samuel refused to declare his belief in Christianity, and the minister refused to baptize the child. In 1803, most of Polk's relatives moved to the Duck River area in what is now Maury County, Middle Tennessee; Polk's family waited until 1806 to follow. The family grew prosperous, with Samuel Polk turning to land speculation and becoming a county judge. Polk was home schooled. His health was problematic and in 1812 his pain became so unbearable that he was taken to Dr. Ephraim McDowell of Danville, Kentucky, who operated to remove urinary stones. Polk was awake during the operation with nothing but brandy available for anesthetic, but it was successful. The surgery may have left Polk sterile, as he did not sire any children. Polk was admitted to the bar in June 1820 and his first case was to defend his father against a public fighting charge, and secure his release for a one dollar fine. Polk's practice was successful as there were many cases arising from debts after the Panic of 1819. Polk's oratory became popular, earning him the nickname "Napoleon of the Stump." In 1822 Polk resigned his position as clerk to run his successful campaign for the Tennessee state legislature in 1823, in which he defeated incumbent William Yancey, becoming the new representative of Maury County. In October 1823 Polk voted for Andrew Jackson to become the next United States Senator from Tennessee. Jackson won and from then on Polk was a firm supporter of Jackson. Polk courted Sarah Childress, and they married on January 1, 1824. Polk was then 28, and Sarah was 20 years old. They had no children. During Polk's political career, Sarah assisted her husband with his speeches, gave him advice on policy matters and played an active role in his campaigns. In 1825, Polk ran for the United States House of Representatives for the Tennessee's 6th congressional district. Polk vigorously campaigned in the district. Polk was so active that Sarah began to worry about his health. During the campaign, Polk's opponents said that at the age of 29 Polk was too young for a spot in the House, but he won the election and took his seat in Congress. When Polk arrived in Washington, D.C. he roomed in a boarding house with some other Tennessee representatives, including Benjamin Burch. Polk made his first major speech on March 13, 1826, in which he said that the Electoral College should be abolished and that the President should be elected by the popular vote. After Congress went into recess in the summer of 1826, Polk returned to Tennessee to see Sarah, and when Congress met again in the autumn, Polk returned to Washington with Sarah. In 1827 Polk was reelected to Congress. In August 1833, after being elected to this fifth term, Polk became the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. In 1835, Polk ran against Bell for Speaker again and won. Polk issued the gag rule on petitions from abolitionists. Polk initially hoped to be nominated for vice president at the Democratic convention, which began on May 27, 1844. The leading contender for the presidential nomination was former President Martin Van Buren, who wanted to stop the expansion of slavery. The primary point of political contention involved the Republic of Texas, which, after declaring independence from Mexico in 1836, had asked to join the United States, but was refused by Washington. Van Buren opposed the annexation but in doing so lost the support of many Democrats, including former President Andrew Jackson, who still had much influence. Van Buren won a simple majority on the convention's first ballot but did not attain the two-thirds supermajority required for nomination. When it became clear after another six ballots that Van Buren would not win the required majority, Polk emerged as a "dark horse" candidate. After an indecisive eighth ballot, the convention unanimously nominated Polk. Polk's Whig opponent in the 1844 presidential election was Henry Clay of Kentucky. In the election, Polk and his running mate, George M. Dallas, won in the South and West, while Clay drew support in the Northeast. Polk lost both his home state, North Carolina, and his state of residence, Tennessee, the most recent successful presidential candidate to do so. but won New York, where Clay lost votes to the antislavery Liberty Party candidate James G. Birney. Also contributing to Polk's victory was the support of new immigrant voters, who opposed the Whigs' policies. Polk won the popular vote by a margin of about 39,000 out of 2.6 million, and took the Electoral College with 170 votes to Clay's 105. Polk won 15 states, while Clay won 11. During his presidency, many abolitionists harshly criticized him as an instrument of the "Slave Power", and claimed that spreading slavery was the reason he supported annexing Texas and later war with Mexico. Polk stated in his diary that he believed slavery could not exist in the territories won from Mexico, but refused to endorse the Wilmot Proviso that would forbid it there. Polk argued instead for extending the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean, which would prohibit the expansion of slavery above 36° 30' west of Missouri, but allow it below that line if approved by eligible voters in the territory. Polk was a slaveholder for his entire life. His father, Samuel Polk, had left Polk more than 8,000 acres (32 km²) of land, and divided about 53 slaves to his widow and children after he died. James inherited twenty of his father's slaves, either directly or from deceased brothers. In 1831, he became an absentee cotton planter, sending slaves to clear plantation land that his father had left him near Somerville, Tennessee. Four years later Polk sold his Somerville plantation and, together with his brother-in-law, bought 920 acres (3.7 km²) of land, a cotton plantation near Coffeeville, Mississippi. He ran this plantation for the rest of his life, eventually taking it over completely from his brother-in-law. Polk rarely sold slaves, although once he became President and could better afford it, he bought more. Polk's will stipulated that their slaves were to be freed after his wife Sarah had died. However, the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution freed all remaining slaves in rebel states long before the death of his wife in 1891. After the Texas annexation, Polk turned his attention to California, hoping to acquire the territory from Mexico before any European nation did so. The main interest was San Francisco Bay as an access point for trade with Asia. In 1845, he sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico to purchase California and New Mexico for $24–30 million. Slidell's arrival caused political turmoil in Mexico after word leaked out that he was there to purchase additional territory and not to offer compensation for the loss of Texas. The Mexicans refused to receive Slidell, citing a technical problem with his credentials. In January 1846, to increase pressure on Mexico to negotiate, Polk sent troops under General Zachary Taylor into the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande—territory that was claimed by both the U.S. and Mexico. Slidell returned to Washington in May 1846, having been rebuffed by the Mexican government. Polk regarded this treatment of his diplomat as an insult and an "ample cause of war", and he prepared to ask Congress for a declaration of war. Meanwhile Taylor crossed the Rio Grande River and briefly occupied Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Taylor continued to blockade ships from entering the port of Matamoros. Mere days before Polk intended to make his request to Congress, he received word that Mexican forces had crossed the Rio Grande area and killed eleven American soldiers. Polk then made this the casus belli, and in a message to Congress on May 11, 1846, he stated that Mexico had "invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil." Some Whigs, such as Abraham Lincoln, challenged Polk's version of events, but Congress overwhelmingly approved the declaration of war. Many Whigs feared that opposition would cost them politically by casting themselves as unpatriotic for not supporting the war effort. Polk selected the top generals and set the military strategy of the war. By the summer of 1846, American forces under General Stephen W. Kearny had captured New Mexico. Meanwhile, Army captain John C. Frémont led settlers in northern California to overthrow the Mexican garrison in Sonoma (in the Bear Flag Revolt). General Zachary Taylor, at the same time, was having success on the Rio Grande, although Polk did not reinforce his troops there. The United States also negotiated a secret arrangement with Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican general and dictator who had been overthrown in 1844. Santa Anna agreed that, if given safe passage into Mexico, he would attempt to persuade those in power to sell California and New Mexico to the United States. Once he reached Mexico, however, he reneged on his agreement, declared himself President, and tried to drive the American invaders back. Santa Anna's efforts, however, were in vain, as Generals Taylor and Winfield Scott destroyed all resistance. Scott captured Mexico City in September 1847, and Taylor won a series of victories in northern Mexico. Even after these battles, Mexico did not surrender until 1848, when it agreed to peace terms set out by Polk. In mid-1848, President Polk authorized his ambassador to Spain, Romulus Mitchell Saunders, to negotiate the purchase of Cuba and offer Spain up to $100 million, an astounding sum at the time for one territory, equal to $2.69 billion in present day terms. Cuba was close to the United States and had slavery, so the idea appealed to Southerners but was unwelcome in the North. But Spain was still making huge profits in Cuba (notably in sugar, molasses, rum, and tobacco), and the Spanish government rejected Saunders' overtures. Polk's time in the White House took its toll on his health. Full of enthusiasm and vigor when he entered office, Polk left on March 4, 1849, exhausted by his years of public service. He lost weight and had deep lines on his face and dark circles under his eyes. He is believed to have contracted cholera in New Orleans, Louisiana, on a goodwill tour of the South. He died at his new home, Polk Place, in Nashville, Tennessee, at 3:15 pm on June 15, 1849, three months after leaving office. He was buried on the grounds of Polk Place. Polk's last words illustrate his devotion to his wife: "I love you, Sarah. For all eternity, I love you." She lived at Polk Place for over forty years after his death. She died on August 14, 1891.

Texas Independence(No tricks on this photo, the wind cutting between the buildings held this for about 5 seconds before both flags flew in the same direction). TEXAS' first president, Sam Houston ran away from home at the age of 16 to live with the Cherokee, was adopted into the Cherokee Nation and given the name Colonneh or "the Raven". Houston fought the British on the American side of the War of 1812. Wounded by a Creek indian arrow, he recovered and answered Andrew Jackson's call for volunteers to dislodge a group of Red Sticks (Creek fighting for the British) from fortified positions. He suffered bullets in the shoulder and arm, but recovered again. In 1817, he was appointed sub-agent managing the business relating to the removal of the Cherokees from East Tennessee, but instead appeared before the US Secretary of War in his Native American garments. Houston resigned the post. Houston signed the Texas Declaration of Independence, and commanding the Texas army, defeated Santa Anna and the Mexican forces to win our independence. Twice President of the Republic of Texas, he later served as a US Senator, and Texas Governor. He was thrown out of office for refusing to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy writing: "Fellow-Citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies ... I refuse to take this oath." Sam died with his wife Margaret by his side, his last words were "Texas. Texas. Margaret".

Alamo, San AntonioIn Mexico, this is referred to as The American Intervention (La Intervención Estadounidense). Mexico had claimed the area in question for about 25 years since the winning of its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821 following the Mexican War of Independence. The Spanish Empire had conquered part of the area from the Native American tribes over the preceding three centuries, but there remained rather powerful and independent indigenous nations within that northern region of Mexico. Most of that land was too dry (low rainfall) and too mountainous or hilly to support very much population until the advent of new technology following about 1880: means for damming and distributing water from the few rivers to irrigated farmland; the telegraph; the railroad; the telephone; and electrical power. There were about 80,000 Mexicans living in the areas of California, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas during the period of 1845 – 50, and far fewer in Nevada, in southern and western Colorado, and in Utah.[14] On 1 March 1845, U.S. President John Tyler signed legislation to authorize the United States to annex the Republic of Texas, effective on 29 December 1845. The Mexican government, which had never recognized the Republic of Texas as an independent country, had warned that annexation would be viewed as an act of war. The United Kingdom and France, both of which recognized the independence of the Republic of Texas, repeatedly tried to dissuade Mexico from declaring war against its northern neighbor. British efforts to mediate the quandary were fruitless – in part because additional political disputes (particularly the Oregon boundary dispute) arose between Great Britain, as the sovereign of Canada, and the United States. Before the outbreak of hostilities, on 10 November 1845, President James K. Polk, had sent his envoy, John Slidell, to Mexico to offer the country around $5 million for the territory of Nuevo México, and up to $40 million for Alta California (the present State of California) .[15] The Mexican government dismissed Slidell, refusing to even meet with him.[16] Earlier in that year, Mexico had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States, based partly on its interpretation of the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 (which newly independent Mexico claimed it had inherited). In this one the United States had supposedly "renounced forever" all claims to Spanish territory.[17] Neither side took any further action to avoid a war. Meanwhile Polk settled a major territorial dispute with Britain with the Oregon Treaty, signed on 15 June; this avoided a conflict with Great Britain, and hence gave the U.S. a free hand. After the Thornton Affair of April 25-26, when Mexican forces attacked an American unit in the disputed area with 11 Americans killed, 5 wounded and 49 captured, Congress passed and Polk signed a declaration of war into effect on 13 May 1846. Mexico responded with its war declaration.[citation needed] Map of Mexico. S. Augustus Mitchell, Philadelphia, 1847. Alta California shown including Nevada, Utah, Arizona. [edit] Conduct of warMain article: Mexican–American War California and New Mexico were quickly occupied by American forces in the summer of 1846, and fighting there ended by January 1847 with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga and end of the Taos Revolt. The U.S. spent 1847 invading central Mexico and occupying Mexico City, but Mexico was still reluctant to agree to the loss of California and New Mexico, offering only sale of Alta California north of the 37th parallel north (north of Santa Cruz, California and Madera, California and the southern boundaries of today's Utah and Colorado) which was already dominated by Anglo-American settlers. Some Eastern Democrats called for total annexation of Mexico and claimed that some Mexican liberals would welcome this,[18] but Pres. Polk's State of the Union address in December 1847 upheld Mexican independence and argued at length that occupation and any further military operations in Mexico were aimed at securing a treaty ceding California and New Mexico up to approximately the 32nd parallel north and possibly Baja California and transit rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[16] Jefferson Davis advised Polk that if Mexico appointed commissioners to come to the U.S., the government that appointed them would probably be overthrown before they completed their mission, and they would likely be shot as traitors on their return; so that the only hope of peace was to have a U.S representative in Mexico.[19] Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the State Department under Pres. Polk, finally negotiated a treaty with the Mexican delegation after ignoring his recall by Pres. Polk in frustration with failure to secure a treaty.[20] Notwithstanding that the treaty had been negotiated against his instructions, given its achievement of the major American aim, President Polk passed it on to the Senate.[20] [edit] Treaty of Guadalupe HidalgoA section of the original treaty. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed by Nicholas Trist on behalf of the U.S. and Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto and Miguel Atristain as plenipotentiary representatives of Mexico on 2 February 1848, at the main altar of the old Basilica of Guadalupe at Villa Hidalgo (within the present city limits) as U.S troops under the command of Gen. Winfield Scott were occupying Mexico City. [edit] Changes to the treaty and ratificationThe version of the treaty ratified by the United States Senate eliminated Article X,[21] which stated that the U.S. government would honor and guarantee all land grants awarded in lands ceded to the U.S. to citizens of Spain and Mexico by those respective governments. Article VIII guaranteed that Mexicans who remained more than one year in the ceded lands would automatically become full-fledged United States citizens (or they could declare their intention of remaining Mexican citizens); however, the Senate modified Article IX, changing the first paragraph and excluding the last two. Among the changes was that Mexican citizens would "be admitted at the proper time (to be judged of by the Congress of the United States)" instead of "admitted as soon as possible", as negotiated between Trist and the Mexican delegation. An amendment by Jefferson Davis giving the U.S. most of Tamaulipas and Nuevo Leon, all of Coahuila and a large part of Chihuahua was supported by both senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party, Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray Mason of Virginia and Ambrose Hundley Sevier were opposed and the amendment was defeated 44–11.[22] An amendment by Whig Sen. George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico and California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats. Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding votes for acquiring the new territories. A motion to insert into the treaty the Wilmot Proviso banning slavery failed 15–38 on sectional lines. The treaty was subsequently ratified by the U.S. Senate by a vote of 38 to 14 on 10 March 1848 and by Mexico through a legislative vote of 51 to 34 and a Senate vote of 33 to 4, on 19 May 1848. News that New Mexico's legislative assembly had just passed an act for organization of a U.S. territorial government helped ease Mexican concern about abandoning the people of New Mexico.[23] The treaty was formally proclaimed on 4 July 1848.[24] Protocol of QuerétaroOn 30 May 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further negotiated a three-article protocol to explain the amendments. The first article stated that the original Article IX of the treaty, although replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy of land grants pursuant to Mexican law.[25] The protocol further noted that said explanations had been accepted by the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs on behalf of the Mexican Government,[25] and was signed in Santiago de Queretaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford and Luis de la Rosa. The U.S. would later go on to ignore the protocol on the grounds that the U.S. representatives had over-reached their authority in agreeing to it.[26] [edit] Treaty of MesillaThe Treaty of Mesilla, which concluded the Gadsden purchase of 1854, had significant implications for the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article II of the treaty annulled article XI of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and article IV further annulled articles VI and VII of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article V however reaffirmed the property guarantees of Guadalupe Hidalgo, specifically those contained within articles VIII and IX.[27] [edit] EffectsThe Mexican Cession agreed by Mexico (white) and the Gadsden Purchase (brown). Part of the area marked as Gadsden Purchase near modern-day Mesilla, New Mexico, was disputed after the Treaty. In addition to the sale of land, the treaty also provided for the recognition of the Rio Grande as the boundary between the state of Texas and Mexico.[28] The land boundaries were established by a survey team of appointed Mexican and American representatives,[20] and published in three volumes as The United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. On 30 December 1853, the countries by agreement altered the border from the initial one by increasing the number of border markers from 6 to 53.[20] Most of these markers were simply piles of stones.[20] Two later conventions, in 1882 and 1889, further clarified the boundaries, as some of the markers had been moved or destroyed.[20] Photographers were brought in to document the location of the markers. These photographs are in Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief Engineers, in the National Archives.[citation needed] The southern border of California was designated as a line from the junction of the Colorado and Gila rivers westward to the Pacific Ocean, so that it passes one Spanish league south of the southernmost portion of San Diego Bay. This was done to ensure that the United States received San Diego and its excellent natural harbor, without relying on potentially inaccurate designations by latitude.[citation needed] The treaty extended U.S. citizenship to Mexicans in the newly purchased territories, before many African Americans, Asians and Native Americans were eligible. Between 1850 and 1920, the U.S. Census counted most Mexicans as racially "white",[29] despite the actual mixed ancestry of most Mexicans.[30] Nonetheless, racially tinged tensions persisted in the era following annexation, reflected in such things as the Greaser Act in California, as tens of thousands of Mexican nationals suddenly found themselves living within the borders of the United States. Mexican communities remained segregated de facto from and also within other U.S. communities, continuing through the Mexican migration right up to the end of the 20th century throughout the Southwest.[citation needed] Community property rights in California are a legacy of the Mexican era. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that the property rights of Mexican subjects would be kept inviolate. The early Californians felt compelled to continue the community property system regarding the earnings and accumulation of property during a marriage, and it became incorporated into the California constitution.[citation needed] [edit] Additional issuesBorder disputes continued. The U.S.'s desire to expand its territory continued unabated and Mexico's economic problems persisted,[31] leading to the controversial Gadsden Purchase in 1854 and William Walker's Republic of Lower California filibustering incident in that same year.[citation needed] The Channel Islands of California and Farallon Islands are not mentioned in the Treaty.[32] The border was routinely crossed by the armed forces of both countries. Mexican and Confederate troops often clashed during the American civil war, and the U.S. crossed the border during the war of French intervention in Mexico. In March 1916 Pancho Villa led a raid on the U.S. border town of Columbus, New Mexico, which was followed by the Pershing expedition. The shifting of the Rio Grande would much later cause a dispute over the boundary between purchase lands and those of the state of Texas, called the Country Club Dispute.[citation needed] Controversy over community land grant claims in New Mexico persists to this day.[33] Disputes about whether to make all this new territory into free states or slave-holding states contributed heavily to the rise in North-South tensions that led to the United States Civil War just over a decade later.[citation needed] The treaty was leaked to John Nugent before the U.S. Senate could approve it. Nugent published his article in the New York Herald and, afterward, was questioned by Senators. Nugent did not reveal his source.[citation needed] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo led to the establishment in 1889 of the International Boundary and Water Commission to maintain the border, and pursuant to newer treaties to allocate river waters between the two nations, and to provide for flood control and water sanitation. Once viewed as a model of international cooperation, in recent decades the IBWC has been heavily criticized as an institutional anachronism, by-passed by modern social, environmental and political issues.[ |

Texas War - Sam Houston at San JacintoThe Texas Revolution, also known as the Texas War of Independence, was the military conflict between the government of Mexico and Texas colonists that began October 2, 1835 and resulted in the establishment of the Republic of Texas after the final battle on April 21, 1836. Intermittent conflicts between the two nations continued into the 1840s, finally being resolved with the Mexican–American War of 1846 to 1848 after the annexation of Texas to the United States. Long-running political and cultural clashes between the Mexican government and the settlers in Texas were exacerbated after conservative forces took control and the Siete Leyes (Seven Laws) of 1835 were approved. It displaced the federal Constitution of 1824 with the 1835 Constitution of Mexico, thereby ending the federal system and establishing a provisional centralized government in its place. The new laws were unpopular throughout Mexico, leading to secession movements and violence in several Mexican states.

San AntonioSan Antonio Texas River Walk Alamo Open warfare began in Texas on October 2, 1835, with the Battle of Gonzales. Early Texan Army successes at La Bahía and San Antonio (Battle of Goliad, Siege of Béxar) were soon reversed when the Mexican Army retook the territory a few months later (Battle of Coleto, Battle of the Alamo). The war ended at the Battle of San Jacinto, where the Texian army under General Sam Houston routed the Mexican forces with a surprise attack. The Mexican War for Independence (1810–1821) severed control that Spain had exercised on its North American territories, and the new country of Mexico was formed from much of the individual territory that had comprised New Spain. On October 4, 1824, Mexico adopted a new constitution which defined the country as a federal republic with nineteen states and four territories. The former province of Spanish Texas became part of a newly created state, Coahuila y Tejas, whose capital was at Saltillo, hundreds of miles from the former Texas capital, San Antonio de Bexar (now San Antonio, Texas, USA). The new country emerged essentially bankrupt from the war against Spain. With little money for the military, Mexico encouraged settlers to create their own militias for protection against hostile Indian tribes. Texas was very sparsely populated and in the hope that an influx of settlers could control the Indian raids, the government liberalized immigration policies for the region. The first group of colonists, known as the Old Three Hundred, had arrived in 1822 to settle an empresarial grant that had been given to Stephen F. Austin. Of the 24 empresarios, only one settled citizens from within the Mexican interior; most of the remaining settlers came from the United States. The Mexican-born settlers in Texas were soon vastly outnumbered by people born in the United States. To address this situation, President Anastasio Bustamante implemented several measures on April 6, 1830. Chief among these was a prohibition against further immigration to Tejas from the United States, although American citizens would be allowed to settle in other parts of Mexico. Furthermore, the property tax law, intended to exempt immigrants from paying taxes for ten years, was rescinded, and tariffs were increased on goods shipped from the United States. Bustamante also ordered all Tejas settlers to comply with the federal prohibition against slavery or face military intervention. These measures did not have the intended effect. Settlers simply circumvented or ignored the laws. By 1834, it was estimated that over 30,000 Anglos lived in Coahuila y Tejas, compared to only 7,800 Mexican-born citizens. By 1836, there were approximately 5,000 slaves in Texas. Texans were becoming increasingly disillusioned with the Mexican government. Many of the Mexican soldiers garrisoned in Texas were convicted criminals who were given the choice of prison or serving in the army in Texas. One possible issue and motivation for the revolution was Mexico's prohibition of slavery. The Mexican government had invited immigrants to Mexican Texas with the understanding that they would produce food crops, insisting upon production of corn, grain and beef. Former American settlers found such micromanagement of the land use to be opposed to their economic interests in slavery. They tended to ignore their contracts. If these were enforced, Texas slave-owners stood to lose a large investment in slave labor. Cotton was in high demand throughout Europe and so a lucrative export throughout the southern United States. Much of the land being opened up to Anglos in Mexican Texas was well suited for cotton, but raising cotton was a labor intensive endeavor at the time, and many Texans thought that slave-labor was more profitable. Most of the American settlers in Mexico were from southern states, where slavery was still legal. They even brought their slaves with them. Because slavery was illegal in Mexico, these settlers made their slaves sign agreements giving them the status of indentured servants – essentially slavery by another name. The Mexican authorities nominally regulated this practice, and the issue continued to flare up, especially when slaves escaped. By the 1830s, many settlers were afraid that the Mexicans would take the slaves away, which made them favor independence. Some non-slave-owning settlers recognized the economic impact of the prohibition, and as potential beneficiaries of the slave-based economy, supported independence as well. The significance of slavery in the Texas War for Independence is unclear and difficult to determine. It is important to address the fact that the Texas Declaration of Independence of 1836 does not mention slavery, unlike Texas' 1861 Ordinance of Secession. Furthermore, the vast majority of primary-sources from the period do not mention slavery as a cause, but rather focus on issues such as religious freedom, the abrogation of the Mexican Constitution, and land rights.

Manifest DestinyThis painting (circa 1872) by John Gast called American Progress, is an allegorical representation of the modernization of the new west. Here Columbia, a personification of the United States, leads civilization westward with American settlers, stringing telegraph wire as she sweeps west; she holds a school book. The different stages of economic activity of the pioneers are highlighted and, especially, the changing forms of transportation. Manifest Destiny was the 19th and 20th century American belief that the United States was destined to expand across the North American continent. The concept, born out of "a sense of mission to redeem the Old World," was enabled by "the potentialities of a new earth for building a new heaven." The phrase itself meant many different things to many different people. The unity of the definitions ended at "expansion, prearranged by Heaven." Mid-19th Century Democrats would use it to explain the need for expansion past the Louisiana Territory. Manifest destiny provided the dogma and tone for the largest acquisition of U.S. territory. It was used by Democrats in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico and it was also used to acquire portions of Oregon from the British Empire. The legacy is a complex one. The belief in an American mission to promote and defend democracy throughout the world, as expounded by Abraham Lincoln and later by a more contemporary Woodrow Wilson, continues to have an influence on American political ideology. Journalist John L. O'Sullivan, an influential advocate for Jacksonian democracy and a complex character described by Julian Hawthorne as "always full of grand and world-embracing schemes", wrote an article in 1839[9] which, while not using the term "Manifest Destiny", did predict a "divine destiny" for the United States based upon values such as equality, rights of conscience, and personal enfranchisement "to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation of man". This destiny was not explicitly territorial, but O'Sullivan predicted that the United States would be one of a "Union of many Republics" sharing those values. Six years later, in 1845, O'Sullivan wrote another essay entitled Annexation in the Democratic Review, in which he first used the phrase Manifest Destiny. In this article he urged the U.S. to annex the Republic of Texas, not only because Texas desired this, but because it was "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions". Overcoming Whig opposition, Democrats annexed Texas in 1845. O'Sullivan's first usage of the phrase "Manifest Destiny" attracted little attention. O'Sullivan's second use of the phrase became extremely influential. On December 27, 1845 in his newspaper the New York Morning News, O'Sullivan addressed the ongoing boundary dispute with Britain. O'Sullivan argued that the United States had the right to claim "the whole of Oregon": "And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us." That is, O'Sullivan believed that Providence had given the United States a mission to spread republican democracy ("the great experiment of liberty"). Because Britain would not use Oregon for the purposes of spreading democracy, thought O'Sullivan, British claims to the territory should be overruled. O'Sullivan believed that Manifest Destiny was a moral ideal (a "higher law") that superseded other considerations. O'Sullivan's original conception of Manifest Destiny was not a call for territorial expansion by force. He believed that the expansion of the United States would happen without the direction of the U.S. government or the involvement of the military. After Americans emigrated to new regions, they would set up new democratic governments, and then seek admission to the United States, as Texas had done. In 1845, O'Sullivan predicted that California would follow this pattern next, and that Canada would eventually request annexation as well. He disapproved of the Mexican-American War in 1846, although he came to believe that the outcome would be beneficial to both countries. On January 3, 1846, Representative Robert Winthrop ridiculed the concept in Congress, saying "I suppose the right of a manifest destiny to spread will not be admitted to exist in any nation except the universal Yankee nation." Winthrop was the first in a long line of critics who suggested that advocates of Manifest Destiny were citing "Divine Providence" for justification of actions that were motivated by chauvinism and self-interest. Despite this criticism, expansionists embraced the phrase, which caught on so quickly that its origin was soon forgotten. Historian William E. Weeks has noted that three key themes were usually touched upon by advocates of Manifest Destiny: The origin of the first theme, later known as American Exceptionalism, was often traced to America's Puritan heritage, particularly John Winthrop's famous "City upon a Hill" sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World. In his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, Thomas Paine echoed this notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society: "We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand." The second theme's origination is less precise. A popular expression, America's mission was elaborated by President Abraham Lincoln's description, in his December 1, 1862 message to Congress. He described the United States "the last, best hope of Earth" The "mission" of the United States was elaborated on in Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, in which he interpreted the Civil War as a struggle to determine if any nation with democratic ideals could survive, has been called by historian Robert Johannsen "the most enduring statement of America's Manifest Destiny and mission." The third theme can be viewed as a natural outgrowth of the belief that God had a direct influence in the foundation and further actions of the United States. Clinton Rossiter, a scholar, described this view as summing "that God, at the proper stage in the march of history, called forth certain hardy souls from the old and privilege-ridden nations... and that in bestowing His grace He also bestowed a peculiar responsibility." Americans presupposed that they were not only divinely elected to maintaining the North American continent but "spread abroad the fundamental principles stated in the Bill of Rights." During the Civil War both sides claimed that America's destiny was rightfully their own. Lincoln opposed Southern sectionalism, anti-immigrant nativism, and the imperialism of Manifest Destiny as both unjust and unreasonable. He believed each of these disordered forms of love threatened the inseparable moral and fraternal bonds of liberty and Union that he sought to perpetuate through a patriotic love of country guided by wisdom and critical self-awareness. Lincoln's "Eulogy to Henry Clay", June 6, 1852 provides the most cogent expression of his reflective patriotism. Henry Beecher Stowe identified the South as only doing "the Devil's work" while the North was left "to do the work of God." Alternatively, men like Benjamin Morgan Palmer, minister of the First Presbyterian Church in New Orleans, were championing the destiny God had made for the Confederate States. Palmer delivered a sermon in New Orleans that described the God's mission was inseparable from the South's. | |

|

Storming of Chapultepec – en:Gideon Pillow | Pillow 's attack (September 13, 1847) Description en:Battle of Churubusco | Battle of Churubusco (August 20, 1847) in the en:Mexican-American War Description en:Siege of Veracruz | Bombardment of Vera Cruz (March 1847) Description en:Battle of Contreras | Assault of Contreras (August 19-20, Depiction of the en:Battle of Monterrey | Battle of Monterrey (September 21-23, 1846 Description Battle of Palo Alto near Category:Brownsville, Texas | Brownsville , fought on May 8, 1846 Description en:Battle of Molino del Rey | Molino del Rey – attack upon the casa mata (September 8, 184 Description en:Battle of Molino del Rey | Molino del Rey – attack upon the molino (September 8, 1847 Description en:Battle of Cerro Gordo | Battle of Cerro Gordo (April 18, 1847) Description en:Battle of Buena Vista | Battle of Buena Vista (February 23, 1847) Description General en:Winfield Scott | Scott 's entrance into Mexico |

No comments:

Post a Comment