The American Occupation of Vera Cruz The American Occupation of Vera Cruz |

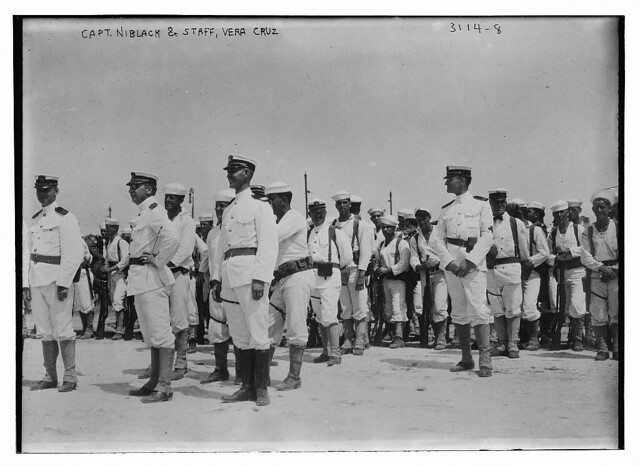

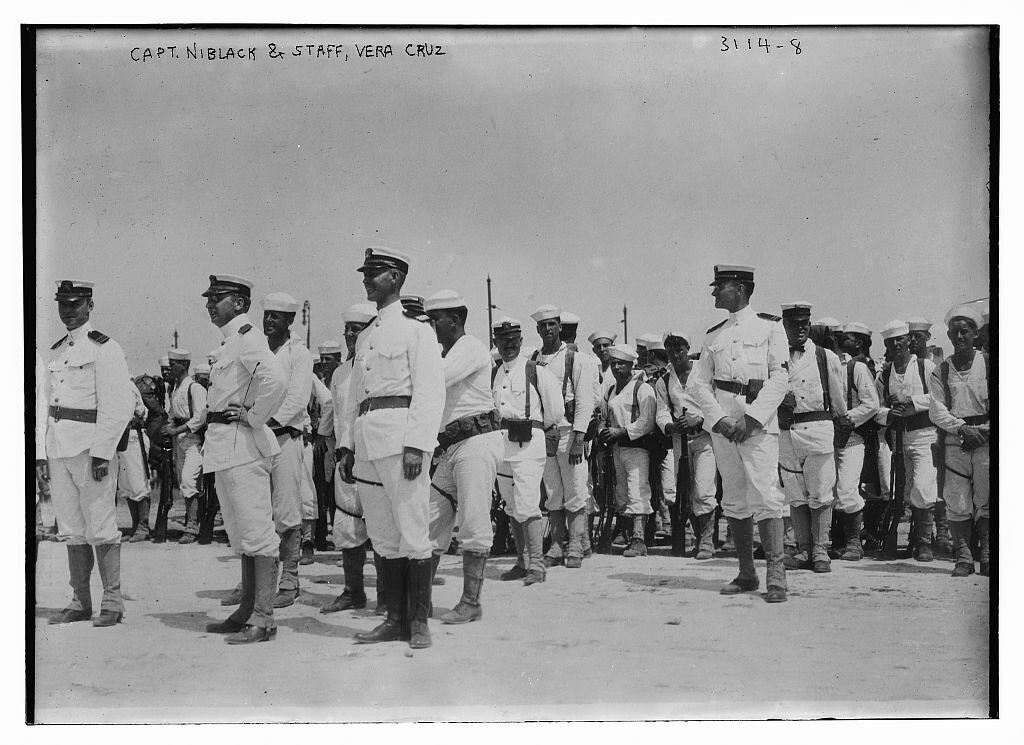

Capt. Niblack & staff, Vera Cruz

Sailors on Water Front, V.C.

Mexican band leading sailors from Vera Cruz |

|

Wilson dispatched a friend, his campaign biographer, William Bayard Hale, to Mexico in 1914. Hale, a New York Timesreporter, spoke no Spanish and had never been in Mexico before. But Wilson trusted Hale, and Hale understood Wilson’s idealistic belief in constitutional democracy. Working undercover1, Hale unsurprisingly reported that Huerta was a tyrant with no popular support. It was control of the oil fields – and the revenues from the oil fields that let him buy foreign munitions – that kept him in power. William Bayard Hale was right: Huerta needed ammunition if he was to maintain power. Everyone knew Britain and Germany were about to go to war. The British Navy depended on Mexican oil, and the British – not caring much who controlled the country as long as they could pump oil – kept a mercenary army under their own general, Manual Perez, protecting the oil region. But Huerta’s forces controlled the ports, and the Germans were willing to supply arms to Huerta in return for blocking oil sales to Britain. Wilson, pro-British, but desperate to keep the United States out of the coming war, hoped that if neither the German nor the British had the clear advantage, the war could be avoided. United States intelligence officers had learned that the Germans were sending several shiploads of arms to Mexico. Carrenza and Huerta had both at various times threatened to cut off oil shipments – which would have kept the British out of the war, but also would cripple the U.S. economy (which even then was dependent on foreign oil imports). Carranza’s forces were slowly taking more and more control of the country, but were unlikely to capture Veracruz in time to stop the Germans from resupplying Huerta. On 6 April, six U.S. sailors were arrested in Tampico, still controlled by Huerta’s administration. The arrests were a mistake, and the sailors were returned to their ship. However, the United States was a new military power in the world, and U.S. officers had not always shown good judgment in Mexico. The United States Navy wanted respect: the ship’s captain demanded an apology from the Mexican Navy … and a 21-gun salute! The Mexicans, politely as possible, apologized for the sailors’ inconvenience, but refused the salute. The “insult to the Navy” received a fair amount of press in the United States. Given the feeling in the United States, this minor incident gave the President a plausible excuse to “avenge the national insult” – and incidentally to cut off Huerta’s arms supplies, and liberate Mexico from the tyrant. Or so it seemed. In 1914 the President of the United States was one of the few people in the world with a bedside telephone. He was still asleep at 6 A.M. on 21 April when he received a call confirming that the German ship, Yripanga, would be docking in Veracruz later that morning. Wilson had the White House operator set up a conference call between himself, his personal secretary, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan and Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels. The operator and the President weren’t the only ones still in their pajamas that morning. Daniels was a pacifist, and Bryan had religious objections to warfare. Still, they agreed with Wilson that the only way to stop the Yripanga was to take over Veracruz. If the French had once invaded the city over unpaid doughnuts in Mexico City, the United States could take the Customs’ House in Veracruz to avenge an insult to its navy’s honor in Tampico. Daniels had orders sent by radio (a very recent technology) to naval ships in the Gulf of Mexico.

Although meant to assist Carranza, even that plan went sour. What Wilson forgot was that Carranza was a very prickly nationalist and had never gotten over his boyhood meeting with Benito Juarez, who had struggled to keep all foreign governments out. Wilson, during his pajama conference, had not consulted the “legitimate” Consitituional Chief of Mexico before sending troops into the country. If the United States did not immediately evacuate Veracruz, the Constitutional Chief threatened to invade the United States, even if it meant joining forces with Huerta! He was bluffing, of course. Wilson was furious, but Carranza had made his point. He – not Huerta – was Mexico’s legitimate leader, and only he had the right to determine Mexico’s foreign policy.

1 Hale was an undercover agent for more than Wilson. He was also a German agent. 2 Sort of. The Yripanga unloaded down the coast in Huerta controlled Puerto Mexico. 3 To legalists like Wilson and Carranza, the terms used in foreign relations were important. Not being president, the constitutional chief could not receive an “ambassador”, but he could receive a “representative”. Historically the Mexican revolution is mostly overlooked in U. S. mainline education systems. Lets review this American History. During the decade of armed revolution (1910-20) the United States mounted two major and one minor armed incursions into Mexican territory: The Marines seized the port of Veracruz in April 1914; General Pershing led a sizable expedition deep into northern Mexico, fruitlessly pursuing Pancho Villa (1916-17); and American forces helped dislodge the ragtag Villista army from Ciudad Jua'rez in June 1919. In the book: Revolutionary Mexico, The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution, it described how the United States during the Mexican Revolution helped the ruling government by stockpiling weapons in Veracruz warehouses. Noteworthy for historians of communications technology and warfare, equipment from the United States sent to Veracruz included 'radio transmitters' and 'shortwave radio sets.' (Hart 1989, 301,302) This was when the use of radio in warfare was still being developed. Voice transmission only became practical 8 years before in 1906.

The United States occupation of Veracruz, which began with the Battle of Veracruz, lasted for six months and was a response to the Tampico Affair of April 9, 1914. The incident came in the midst of poor diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States, related to the ongoing Mexican Revolution. After the Tampico Affair, where nine American sailors were arrested by the Mexican government for entering off-limit areas in Tampico, Mexico,[2] President Woodrow Wilson ordered the United States Navy to prepare for the occupation of the port of Veracruz. While waiting for authorization of Congress to carry out such action, Wilson was alerted to a German delivery of weapons for Victoriano Huerta due to arrive to the port on April 21. As a result, Wilson issued an immediate order to seize the port's customs office and confiscate the weaponry. Huerta had taken over the Mexican government with the assistance of the American ambassador Henry Lane Wilson during a coup d'état in early 1913 known as La decena trágica. The Wilson administration's answer to this was to declare Huerta a usurper of the legitimate government, embargo arms shipments to Huerta, and support the Constitutional Army of Venustiano Carranza. The arms shipment to Mexico, in fact, originated from the Remington Arms company in the U.S. The arms and ammunition were to be shipped via Hamburg, Germany, to Mexico allowing Remington Arms a means of skirting the American arms embargo.[3] On the morning of April 21, 1914, warships of the United States Atlantic Fleet under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, began preparations for the seizure of the Veracruz waterfront. By 11:30, with whaleboats swung over the side, 502 U.S. Marines from the 2nd Advanced Base Regiment, 285 armed Navy sailors, known as "Bluejackets," from the battleship USS Florida and a provisional battalion composed of the Marine detachments of the Florida and her sister ship USS Utah (BB-31) began landing operations. Plowing through the surf in whaleboats toward pier 4, Veracruz's main wharf, a large crowd of Mexican and American citizens gathered to watch the spectacle. The invaders encountered no resistance as they exited the whaleboats, formed ranks into a Marine and a seaman regiment, and began marching toward their objectives. This initial show of force was enough to prompt the retreat of the Mexican forces led by General Gustavo Maass. In the face of this, Mexican Commodore Manuel Azueta encouraged cadets of the Veracruz Naval Academy to take up the defense of the port for themselves. Also, about 50 line soldiers of the Mexican Army remained behind to fight the invaders along with the citizens of Veracruz.

Battle of Veracruz

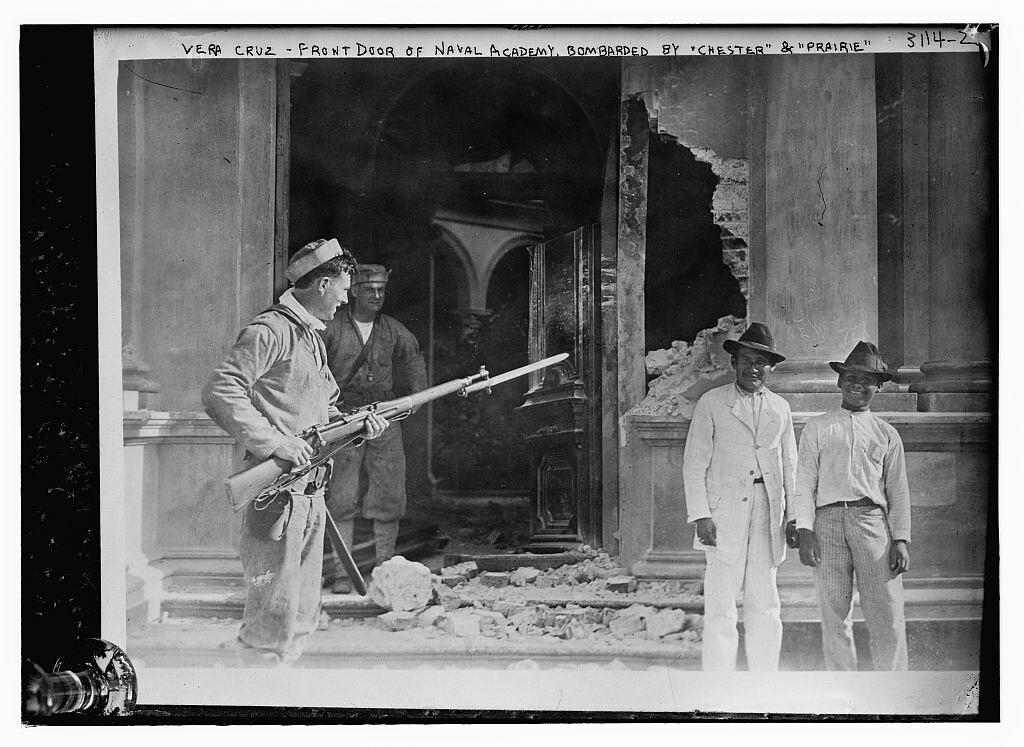

Damaged entryway to a high school adjacent to the Veracruz Naval Academy. The bluejackets were instructed to capture the customs house, post and telegraph offices, while the Marines went for the railroad terminal, roundhouse and yard, the cable office and the powerplant. Soon arms were being distributed to the population, who were largely untrained in the use of Mausers and had trouble finding the correct ammunition. In short, the defense of the city by its populace was hindered by the lack of central organization and a lack of adequate supplies. The defense of the city also included the release of the prisoners held at the San Juan de Ulúa prison. Although the landing had been nearly unopposed as U.S. forces marched into the city, Veracruz was quickly becoming a battleground. Just after noon, fighting began with the 2nd Advance Base Regiment under Colonel Wendell C. Neville becoming heavily involved in a firefight in the rail yards. While the forces ashore slowly fought their way forward, Admiral Fletcher landed the USS Utah's 384 man bluejacket battalion, the only other unit at his disposal. By mid afternoon, the Americans had occupied all of their objectives and Admiral Fletcher called a general halt to the advance, initially hoping that a cease fire could be arranged. That hope however, rapidly faded as he could find no one to bargain with and all troops in the city were instructed to remain on the defensive pending the arrival of reinforcements.

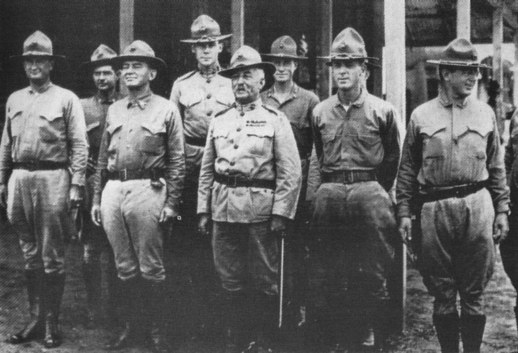

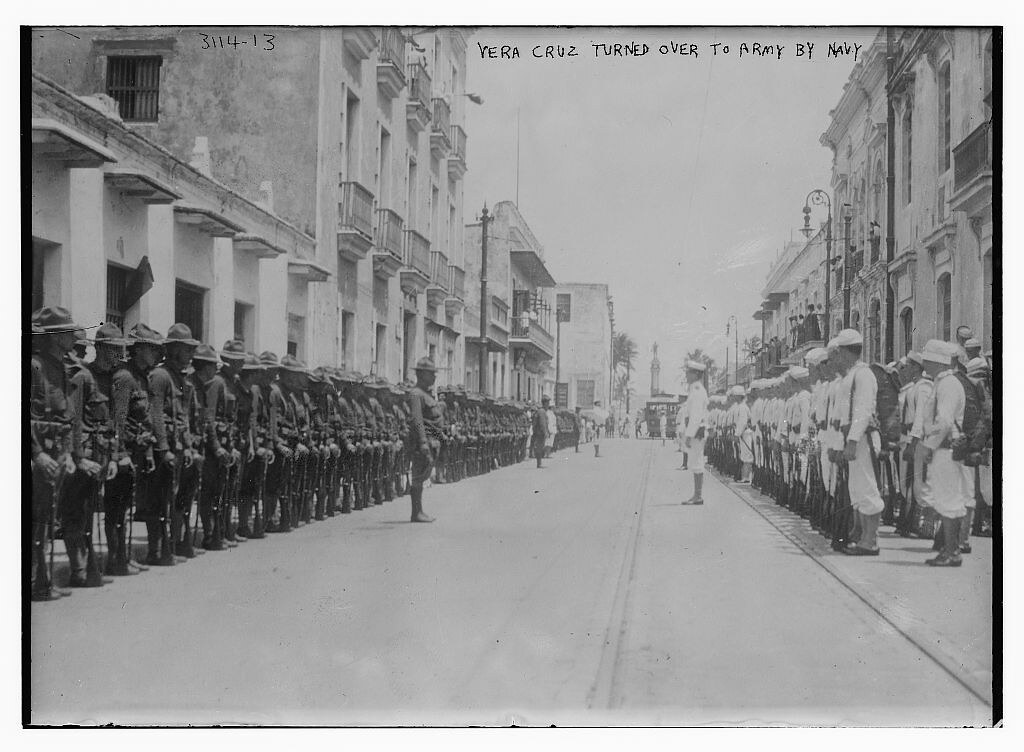

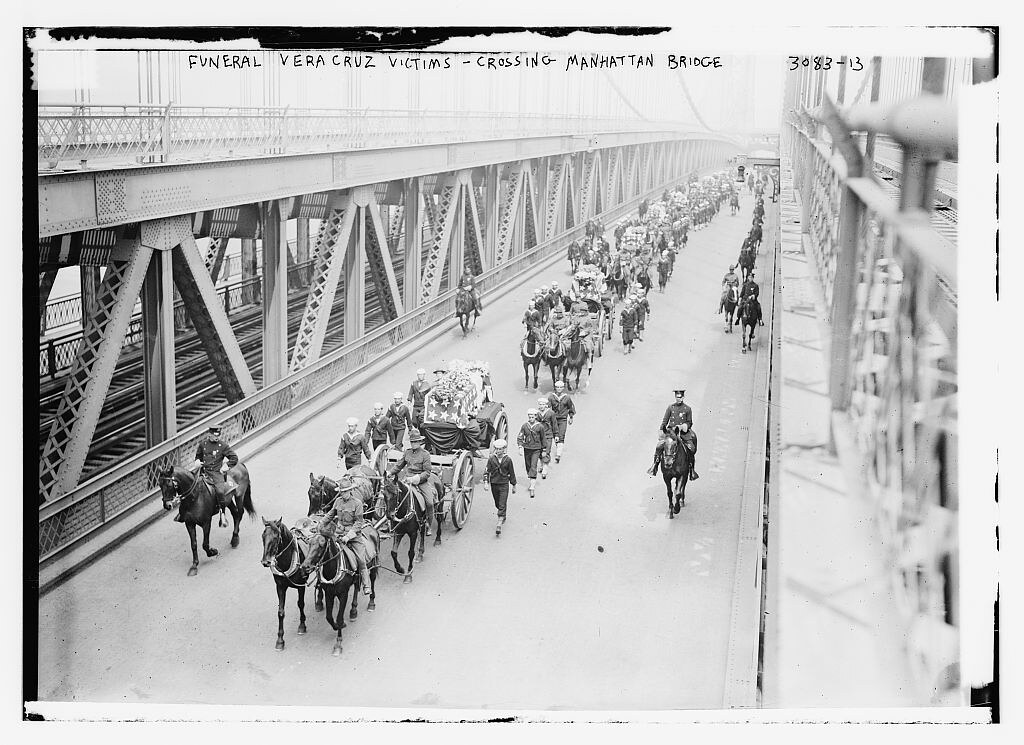

The senior officers of the 1st Marine Brigade photographed at Veracruz in 1914. Front row, left to right: Lt. Col. Wendell C. Neville; Col. John A. Lejeune; Col. Littleton W. T. Waller, Commanding; and Maj. Smedley Butler. On the night of the 21st, Fletcher decided that he had no choice but to expand the initial operation to include the entire city, not just the waterfront.[4] Five additional U.S. battleships and two cruisers had reached Veracruz during the hours of darkness and they carried with them Major Smedley Butler and his Marine Battalion which had been rushed from Panama. The battleship's seaman battalions were quickly organized into a regiment 1,200 men strong, supported by the ship's Marine detachments providing an additional 300-man battalion. These newly arrived forces went ashore around midnight to await the morning's advance. At 07:45, the advance began. The Leathernecks adapted to street fighting, which was a novelty to them. The sailors were less adroit at this style of fighting. A regiment led by Navy Captain E. A. Anderson advanced on the Mexican Naval Academy in parade ground formation, making his men easy targets for the cadets barricaded inside. This attack was repulsed with casualties, and the advance was only saved when three warships in the harbor, the USS Prairie, San Francisco, and Chester, pounded the Academy with their long guns for a few minutes, silencing all resistance and killing 15 of the cadets inside. That afternoon, the First Advanced Base Regiment, originally bound for Tampico, Tamaulipas, came ashore under the command of Colonel John A. Lejeune and by 17:00, U.S. troops had secured the town square and were in complete control of Veracruz. Some pockets of resistance continued to occur around the port, mostly in the form of hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, but by April 24 all fighting had ceased. A third provisional regiment of Marines, assembled at Philadelphia, arrived on May 1 under the command of Colonel Littleton W. T. Waller, who assumed overall command of the Brigade, by that time numbering some 3,141 officers and men. By then, the sailors and Marines of the Fleet had returned to their ships and an Army Brigade had landed. Marines and soldiers continued to garrison the city until the U.S. withdrawal on November 23, which occured after Argentina, Brazil and Chile (the three ABC Powers) were able to settle the issues between the two nations. AftermathJosé Azueta is considered a Mexican hero for his actions during the battle The son of Commodore Azueta, Lieutenant José Azueta, was wounded during the defense of the Naval Academy building. A cadet himself, José Azueta was manning a machine gun placed outside the building, facing the incoming American troops on his own and causing a number of casualties. José Azueta was rescued from the battlefield after sustaining two bullet wounds and taken to his home. After the battle, Admiral Fletcher heard of Azueta's actions in battle and sent his personal doctor to take care of him. However, Azueta refused medical services offered by the occupation army and only allowed local Dr. Rafael Cuervo Xicoy to examine him. Dr. Xicoy lacked medical supplies to assist Azueta properly. Azueta died of his wounds on May 10, Mexico's Mother's Day. During his funeral hundreds of citizens marched holding his coffin on their shoulders to the city's cemetery in open defiance of directives from the occupation army forbidding the right of assembly. U.S. Army Brigadier General Frederick Funston was placed in control of the administration of the port. Assigned to his staff as an intelligence officer was a young Captain Douglas MacArthur.[6] While Huerta and Carranza officially objected to the occupation, neither was able to oppose it effectively, being more preoccupied by events of the Mexican Revolution. Huerta was eventually overthrown and Carranza's faction took power. The occupation, however, brought the two countries to the brink of war and worsened U.S.-Mexican relations for many years. The ABC Powers held the Niagara Falls peace conference in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, on May 20 to avoid an all-out war over this incident. A plan was formed in June for the US troops to withdraw from Veracruz after General Huerta surrendered the reins of his government to a new regime and Mexico assured the United States that it would receive no indemnity for it's losses in the recent chaotic events. [7] Huerta soon afterwards left office and gave his government to Carranza. Carranza, who was still quite unhappy with US troops occupying Veracruz,[7] rejected the rest of the agreement.[7] In November of 1914, following the Convention of Aguascalientes, Carranza left office for a short period and handed control to Eulalio Gutiérrez Ortiz. Ortiz accepted the rest of the agreement and US troops departed on November 23.[7] Despite their previous spat, diplomatic ties between the US and the Carranza regime greatly extended following the depature from Veracruz.[7] After the fighting ended, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels ordered that fifty-six Medals of Honor be awarded to participants in this action, the most for any single action before or since. This amount was half as many as had been awarded for the Spanish-American War, and close to half the number that would be awarded during World War I and the Korean War. A critic claimed that the excess medals were awarded by lot.[8][9] Major Smedley Butler, a recipient of one of the nine Medals of Honor awarded to Marines, later tried to return it, being incensed at this "unutterable foul perversion of Our Country's greatest gift"[citation needed] and claiming he had done nothing heroic. The Department of the Navy told him to not only keep it, but wear it. Lt. Azueta and a Naval Military School cadet, Cadet Midshipman Virgilio Uribe, who also died during the fighting, are now part of the list of honor read by all branches of the Mexican Armed Forces in all military occasions, alongside the six Niños Héroes of the Military College (nowadays the Heroic Military Academy) who died in defense of the nation during the Battle of Chapultepec on Sept. 13, 1846. As a result of the brave defense put up by the Naval School cadets and faculty, it has now become the Heroic Naval Military School of Mexico in their honor. Hall of Fame Major League Baseball star Sam Rice served in the incident before he played Major League Baseball. He joined the Navy after his entire family was killed in a tornado. |

Vera Cruz -- Front door of Naval Ac. Bombarded by CHESTER & PRAIRIE (LOC)Bain News Service,, publisher. Vera Cruz -- Front door of Naval Ac. Bombarded by CHESTER & PRAIRIE [between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915] )

)

)

)

Between 6 July 1913 and 24 September 1915 USS Louisiana made three voyages from east coast ports to Mexican waters. On the first (6 July to 29 December 1913), she stood by to protect American lives and property and to help enforce both the Monroe Doctrine and the arms embargo which had been established to discourage further revolutionary disturbances in Mexico. Her second voyage (14 April to 8 August 1914) came at a time when tension between Mexico and the United States was at its peak during the shelling and occupation of Vera Cruz. Louisiana sailed a third time for Mexican waters to protect American interests again from 17 August to 24 September 1915. |

Woodrow Wilson, who from the Mexican view, should have stayed out of his neighbor’s family feud, felt he had a moral right to intervene in Mexico in 1914. Trained as a Presbyterian minister, the former college professor, and all-round moralist, saw it as his duty to “teach them to elect good men.” He could never understand why the Mexicans rejected him as a guide. The Mexicans resented his meddling, and moreover, what had started the Constitutionalist rebellion was U.S. meddling, specifically Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson’s role in Huerta’s coup at the behest of the dominant foreign economic interests.

Woodrow Wilson, who from the Mexican view, should have stayed out of his neighbor’s family feud, felt he had a moral right to intervene in Mexico in 1914. Trained as a Presbyterian minister, the former college professor, and all-round moralist, saw it as his duty to “teach them to elect good men.” He could never understand why the Mexicans rejected him as a guide. The Mexicans resented his meddling, and moreover, what had started the Constitutionalist rebellion was U.S. meddling, specifically Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson’s role in Huerta’s coup at the behest of the dominant foreign economic interests. Nothing went as planned. As the Spanish found out in 1828, the French in 183, Winfield Scott in 1847, and Maximiliano von Hapsburg in 1863, the “jarochas” do not welcome foreign invasions. In 1848, army cadets had defended Mexico City from United States marines. In 1914, the Naval Academy defended Veracruz. To protect the Marines, the Navy bombarded the city. Citizens joined the cadets. There were casualties on both sides, something a visably shaken and pale Wilson announced to the press the next day. Bryan, who felt personally responsible for the disaster, later resigned. The marines did complete their mission – occupying the Custom’s House. The Yripanga was an unarmed merchant freighter. Its captain was not about to enter a war zone. He turned his ship around. Mission accomplished.

Nothing went as planned. As the Spanish found out in 1828, the French in 183, Winfield Scott in 1847, and Maximiliano von Hapsburg in 1863, the “jarochas” do not welcome foreign invasions. In 1848, army cadets had defended Mexico City from United States marines. In 1914, the Naval Academy defended Veracruz. To protect the Marines, the Navy bombarded the city. Citizens joined the cadets. There were casualties on both sides, something a visably shaken and pale Wilson announced to the press the next day. Bryan, who felt personally responsible for the disaster, later resigned. The marines did complete their mission – occupying the Custom’s House. The Yripanga was an unarmed merchant freighter. Its captain was not about to enter a war zone. He turned his ship around. Mission accomplished.

Henry Lane Wilson, who was still in Mexico City, was finally recalled. The United States sent a representative (not an ambassador

Henry Lane Wilson, who was still in Mexico City, was finally recalled. The United States sent a representative (not an ambassador

No comments:

Post a Comment