|  |

|

|

| THE PEASANT (HUK) INSURRECTION The late 1800s and early 1900s saw the arrival of Americans and the opening up of the Philippine market to the US economy due to American victory in both the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the Philippine-American War in 1902.

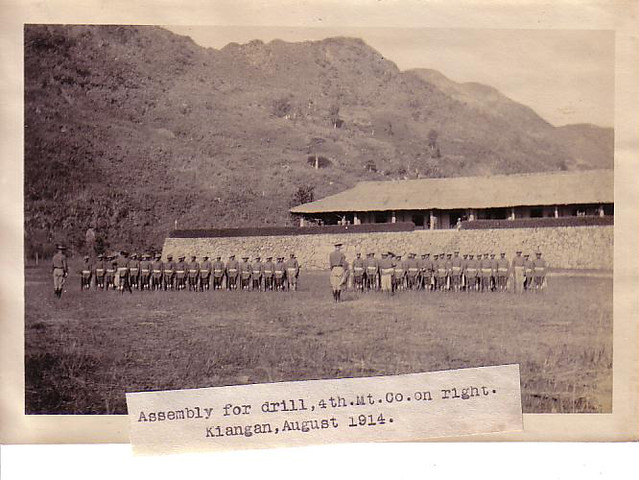

Philippine Fort 1914The arrival of the Americans was characterized by the amplification of capitalism that was instituted by the Spaniards in the encomienda system; there was an exponential increase in the amount of free trade between the Philippines and the United States of America. Agricultural exports to the USA, in the form of 'cash crops', like tobacco and sugar cane, were preferred by landowners more than the usual rice or cereals. It resulted to lesser supply of staple food for the peasant farmers.

There was also changing patterns of farm management. Traditional landowners wanted to modernize their farms and employ tenant-farmers as wage-earners with legal contracts in order to maximize their profit. The following excerpts of Benedict Kerkvliet's interview with Manolo Tinio, one of the landowners during that time in San Ricardo, Talavera, Nueva Ecija (a town in Central Luzon where most of the Huks resided) perfectly captured the general attitude of landowners during that time:

On the padrino relationship "In the old days.. the landlord-tenant relationship was a real paternalistic one. The landlord thought of himself as a grandfather to all tenants, and so he was concerned with all aspects of their lives...But the system had to be changed over time as the hacienda has to be put in a sound economic footing.. The landlord tenant relationship is a business partnership, it is not a family. The landlord has invested capital in the land, and the tenants give their labor." On loans "If the tenants need to borrow rice or money, they could go somewhere else to get it. I decided to lend to only a few tenants, if they pay interest. But to give ration loans and charge no interest, and sometimes not be repaid is certainly an un-businesslike way to handle money."

On contracts "Contracts help to prevent tenants from cheating from me. My father never had problems because the tenants were better people then. But tenants became lazy, and they would take rice and other things that do not belong to them. So each year I made them sign contracts. anyone who didn't want to could go someplace else. And those who didn't abide by the contracts can go someplace else." On machination of farms "I was enthused about putting modern machinery to work like the modern farms I'd seen in the US... The only machine here is the Japanese rice thresher..Meanwhile I try to make the tenants do as I said so the land will be more productive. If you tell a machine something it will do it. It's not the way with tenants.

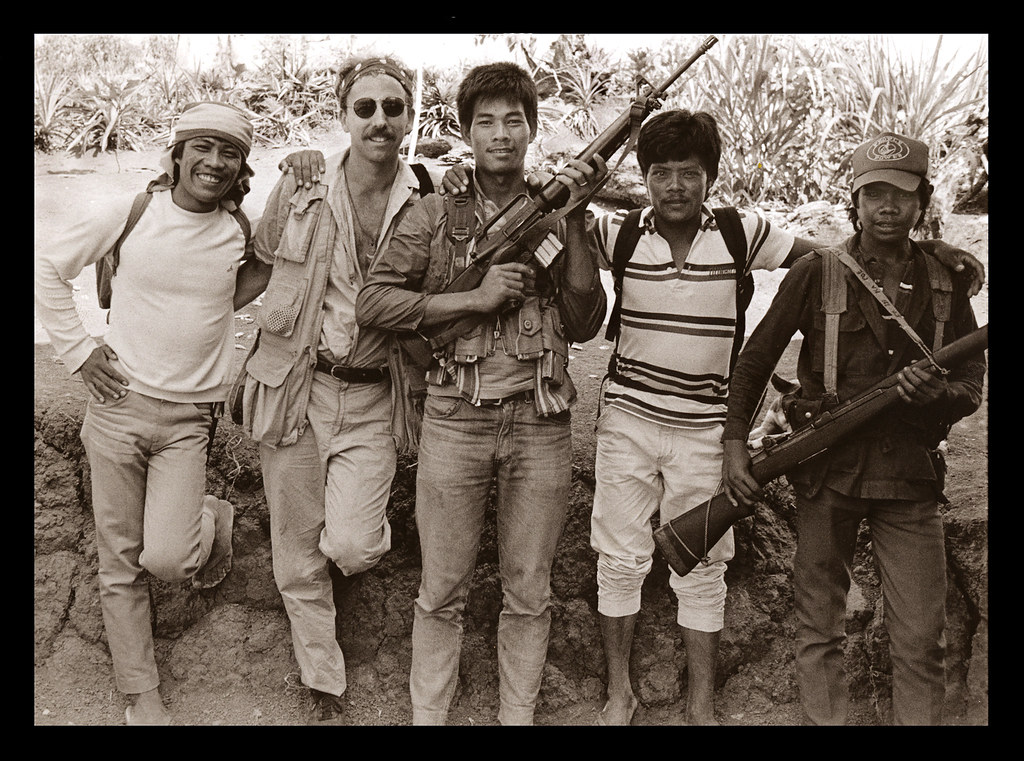

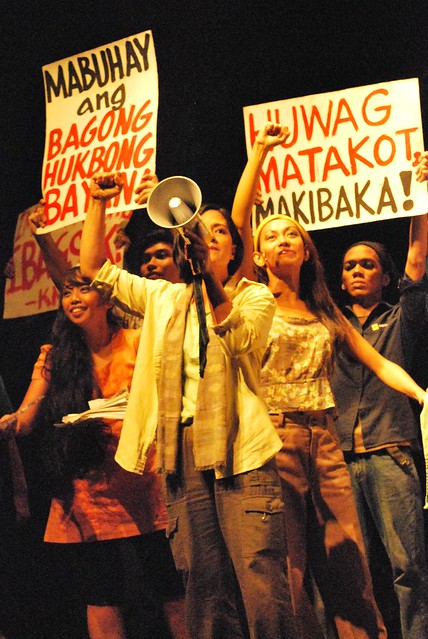

No more Padrino This period saw the collapse of the colonial structures the Spaniards have maintained for more than three centuries. Before, the landowner was very visible. He could be seen attending social functions like weddings and baptisms of his tenants, sponsoring food during fiestas, and inspecting the land. The relationship was very intimate. He helped them in times of distress, especially financial ones, and was seen as a protector from friars and government officials. Now, the landowners were nowhere to be found; the hacienda were left to caretakers. The peasants felt abandoned. The elites have become collaborators of the Americans. If before, they looked to the masses to legitimize their place in society, now they looked to Manila. As a result, peasants started looking for other landowners, only to find out the situation elsewhere is no better and that some peasants have it worse. Hence, there was a growing unrest among the peasantry, which was characterized by small protests against their own landlords. This situation was especially true in the Central Luzon area of the Philippines. The sudden and extreme gap between the landlord and the tenant is seen as the main cause of the peasant unrest. Peasant Organizations As originally constituted in March of 1942, the Hukbalahap was to be part of a broad united front resistance to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[14] This original intent is reflected in its name: "Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon", which was "People's Army Against the Japanese" when translated into English. The adopted slogan was "Anti-Japanese Above All". The Huk Military Committee was at the apex of Huk structure and was charged to direct the guerrilla campaign and to lead the revolution that would seize power after the war.[15] Luis Taruc; a communist leader and peasant-organizer from a barrio in Pampanga; was elected as head the committee, and became the first Huk commander called "El Supremo". The Huks began their anti-Japanese campaign as five 100-man units. They obtained needed arms and ammunition from Philippine army stragglers, which were escapees from the Battle of Bataan and deserters from the Philippine Constabulary, in exchange of civilian clothes. The Huk recruitment campaign progressed more slowly than Taruc had expected, due to U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE) guerrilla units, of which Ramon Magsaysay was included. The U.S. units already had recognition among the islands, had trained military leaders, and an organized command and logistical system.[15] Despite being restrained by the American sponsored guerrilla units, the Huks nevertheless took to the battlefield only 500 men and much fewer weapons. Several setbacks at the hands of the Japanese and with less than enthusiastic support from USAFFE units did not hinder the Huks growth in size and efficiency throughout the war, developing into a well trained, highly organized force with some 15,000 armed fighters by war's end.

By 1950, the Communist Party of the Philippines PKP had resolved to reconstitute the organization as the armed wing of a revolutionary party, prompting a change in the official name to Hukbong Mapalaya ng Bayan, (HMB) or "Peoples' Liberation Army," likely in emulation of the Chinese People's Liberation Army.

Post war Manila, Philippines; desolate Filipinos among the ruins... Chinese characters mean “Long live the Japanese Imperial Army”Desolate Filipinos among the ruins of a once beautiful city. I see no smiles in this picture. Only long faces seeming to say: what future can I have now? So many questions… one that continues to stick in my mind that I have a difficult time trying to understand… why?… what good could have been expected by the devastation of a people and property here in Manila and throughout the Philippines an innocent country that was pulled into this war by no fault of their own? So long ago but still today I am saddened. Notwithstanding this name change, the HMB continued to be popularly known as the Hukbalahap, and the English-speaking press continued to refer to it and its members, interchangeably, as "The Huks" during the whole period between 1945 and 1952. HistoryThe Hukbalahap movement has deep roots in the Spanish encomienda, a system of grants to reward soldiers who had conquered New Spain, established about 1570. This developed into a system of exploitation. In the 19th century, Filipino landlordism, under the Spanish colonization, arose and, with it, further abuses.Only after the coming of the Americans were reforms initiated to lessen tensions between tenants and landlords. The reforms, however, did not solve the problems and, with growing political consciousness produced by education, peasants began to unite under educated but poor leaders. The most potent of these organizations was the Hukbalahap, which began as a resistance organization against the Japanese but ended as an anti-government resistance movement. World War II After the Japanese invasion, peasant leaders met on March 29, 1942 in a forest clearing located in Sitio Bawit, Barrio San Julian, Cabiao, Nueva Ecija, at the junction of Tarlac, Pampanga, and Nueva Ecijaprovinces to form a united organization. "Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon" was chosen as the name of the organization. After the meeting, a military committee was formed with Luis Taruc (chairman), Castro Alejandrino (2nd in command), Bernardo Poblete ("Banal"), and Felepa Culala ("Dayang-Dayang" – an amazon whose unit had killed several Japanese soldiers) as members.[5] The strength of the Huk organization came from the mostly agrarian peasants of Central Luzon. The group's leaders, among them figurehead Luis Taruc, communist party Secretary General Jesus Lava, and Commander Hizon (Benjamin Cunanan), aimed to lead the Philippines toward Marxist ideals and communist revolution. The Hukbalahap Insurrection (1946–1954) was their attempt to take over the Philippines. The Hukhbalahap's methods were often portrayed by other guerrilla leaders as terrorist; for example, Ray C. Hunt, an American who led his own band of 3000 guerrillas, said of the Hukbalahap that

However, the Hukbalahap claimed that it extended its guerrilla warfare campaign for over a decade merely in search of recognition as World War II freedom fighters and former American and Filipino allies who deserved a share of war reparations. After its inception, the group grew quickly and by late summer 1943 claimed to have 15,000 to 20,000 active men and women military fighters and 50,000 more in reserve. These fighters' weaponry was obtained primarily by stealing it from battlefields and downed planes left behind by the Japanese, Filipinos and Americans. They fought Japanese troops to rid the country of its imperialist occupation, worked to subvert the Japanese tax-collection service, intercepted food and supplies to the Japanese troops, and created a training school where they taught political theory and military tactics based on Marxist ideas. In areas that the group controlled, they set up local governments and instituted land reforms, dividing up the largest estates equally among the peasants and often killing the landlords. When it became evident that Manuel Roxas, whom the Huks accused of having been a collaborator, would run for the presidency the Huks allied themselves with the Democratic Alliance, a new political party, and threw their support behind President Sergio Osmeña. When Roxas won the Presidency, he instituted a campaign against the Huks. The Huks, however, succeeded in electing Taruc and other members of the Democratic Alliance to Congress.[7] After Taruc was unseated by the Liberal Party, the Huks retreated to the jungle and began their open rebellion. Between 1946 and 1949 the indiscriminate counterinsurgency measures by President Roxas ("mailed fist" policies) strengthened Huk appeal. The Philippine Army, Philippine Constabulary, and civilian guards attacked villages seeking out subversives. Amidst great fanfare, the Republic of the Philippines was born on 4 July 1946. After the celebrations ended however, the government had to face the realities of sovereignty, a faltering economy, and widespread poverty, especially in Luzon. In Manila, the city once called "the pearl of the Orient," a million people lived in shambles, little improved since the departure of the Japanese. The barrios were full of unemployed Filipinos who arrived during and after the war to seek shelter and jobs but, unfortunately, found neither. The youth grew restless and resented the government that expressed little concern for their plight. The new Philippine government, that had run nearly all of the nation's internal affairs during the commonwealth period, now had sole responsibility for solving the people's problems. Established using the American model of government, an expected result of the country's association with the United States since the end of the nineteenth century, the Philippines had a bicameral legislature and an executive branch consisting of a president and vice-president elected for a four year term and limited to two consecutive terms of office. Beneath the office of the President were ten executive departments, much the same in form and function as U.S. cabinet departments. A singular departure from the American system was the right of the president to suspend, remove, or replace local mayors or governors at his discretion. The final government body, the judiciary, consisted of a supreme court and subordinate statutory courts scattered throughout the islands. All of the justices were appointed by the president and approved by the legislative Commission on Appointments The 1946 Elections In preparation for the nation's first post-independence election, President Osmena released Taruc and Alejandrino from the Iwahig Prison in September. Both leaders had long anticipated the importance of the post-independence elections to establish a permanent position within the government for their movement. This had been the prime reason for the formation of the Democratic Alliance, the political alliance between the CPP and other socialist /communist groups during the liberation period. The two returned immediately to central Luzon and began to plan the Democratic Alliance's campaign for the November election but never fully regained absolute control of the political organization. However, the failure to recapture their political positions was made less dramatic because of a spilt within the ruling Partido Nacionalista. President Osmena and Manuel Roxas, his chief opponent within the party, were divided on the issue of how to handle Huk resistance in Luzon. Osmena favored negotiation, while Roxas proposed elimination. After heated debate and intense internal maneuvering, Osmena retained control of the Nationalist Party and was nominated as its presidential candidate in 1946. Roxas, bitter after his failure to capture the party, left and formed the Liberal Party that, not surprisingly, nominated him as their candidate. Not yet strong enough to nominate a viable candidate for the presidency and afraid that a three way race would guarantee victory for Roxas, the Democratic Alliance threw its support behind Osmena, the more liberal of the two major candidates. For the time, the Alliance was content to run candidates for regional office throughout central Luzon. Campaigning during the fall of 1946 was intense and often violent. Roxas promised that, if elected, he would eliminate Huk resistance within sixty days of his inauguration, and instituted a campaign of terror and intimidation to ensure victory. Huk members of the Democratic Alliance responded with their own counter-terror campaign directed against Roxas' supporters and increased their efforts on behalf of their own candidates in central Luzon. The peasant electorate was trapped between the two warring factions, becoming more and more alienated from the central government as the violence continued.

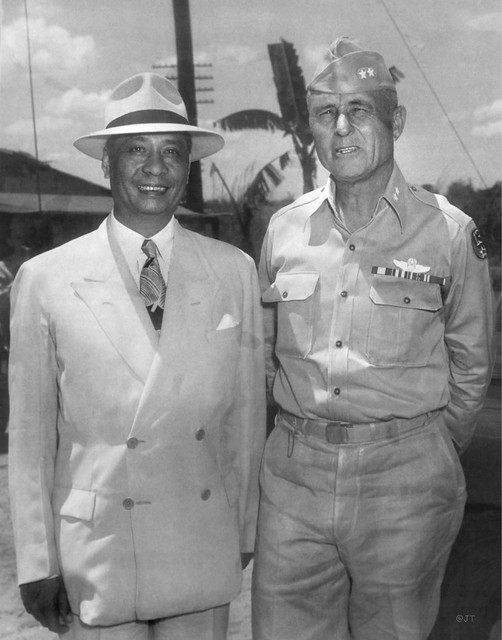

Philippine President Manuel Roxas, and U.S. Major General E. L. Eubank, April 15, 1948President Manuel Roxas, and Major General E. L. Eubank, Commanding General of the 13th Air Force who was host to President Roxas during his official visit to the U.S. Air Base (Clark) in Central Luzon on April, 15, 1948. President Roxas died at Gen. Eubank’s residence approximately seven hours after the photograph was taken. In November, Roxas won the victory on the national level, but lost heavily in central Luzon. The Democratic Alliance elected six congressmen to the legislature in Manila from the provinces of Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, Pampanga, and Bulacan. Despite Roxas' victory, Huk supporters saw a glimmer of hope because of their regional success in the election. However, these hopes were dashed when Democratic Alliance congressmen-elect, including Luis Taruc, went to Manila to take their seats in Congress.3 Roxas intended to live up to his campaign promise of ridding the islands of the Huks after his inauguration in early 1947. His first step was to use his influence within Congress to deny the Alliance congressmen their seats, along with three

July 4, 1946: Republic Day and the second inaugural of President Manuel RoxasThe independence of the Philippines—and the inauguration of its Third Republic—was marked by Manuel Roxas re-taking his oath as President of the Philippines, eliminating the pledge of allegiance to the United States of America, which was required prior to independence. Nacionalista senators whom he felt were allied with the DA. Refused his seat, Taruc returned to the mountains near Mount Arayat in May 1947 and reorganized the Huk General Headquarters. President Roxas then declared a virtual nationwide "open season" on the Huks. The Philippine Military Police Command, reorganized with the Police Constabulary after the war, joined Civil Guards (paramilitary units raised by provincial governors) on indiscriminate "Huk Hunts" wherever they thought Huks or their sympathizers were located. As these government-sanctioned groups scoured the countryside in search of Huks, they spread terror throughout local populations. Preying on the people for supplies, food, and information (often obtained through intimidation and torture) they provided opportune and popular targets for Taruc's forces. They proved the best recruiters for the Huks, who gained new members with each passing day.7 This was the real start of the insurrection.

President Manuel Roxas taking his oath of office, 1946President Roxas takes his oath of office during the Independence Ceremony of July 4, 1946. Administering the oath is Chief Justice Manuel Moran. Beside President Roxas is his First Lady Trinidad. "Huklandia" and the Peasants When the Huk guerrillas again took to the mountains, they chose central Luzon for their base of operations -- the traditional land from which they had fought against the Japanese and from which countless generations of guerrillas had sought sanctuary from oppressive regimes, whether Spanish, American, Japanese, or Philippine. Just as the mountains near Mount Arayat and the Candaba Swamp protected them from the Japanese, so now the land protected them from President Roxas' forces. Surrounded by 6,000 square miles of the richest rice growing region in the Philippines, and supported by local villagers who felt the brunt of government frustrations and 45 inequities, Taruc resumed his plans for the overthrow of the Philippine government. The United States and the Philippines: In Our Image The key to Huk success and persistence stemmed almost entirely from the active support of the local people. Luis Taruc understood them, their desires, aspirations, and, at least during the first phase of the insurrection, used this intimacy to his advantage. When asked why people allied with the his movement, Taruc responded that "People in the barrios ... joined because they had causes - like agrarian reform, government reform, anti-repression,recognition of the Hukbalahap - and , frequently, because they simply had to defend themselves, their very lives against repression."9 Others joined him to revenge the death or abuse of friends and relatives. Still others were so poor and so deeply in debt that they had nothing to lose by backing the rebels. But the one overriding factor that seemed to be central for Huk supporters and converts was the issue of landtenure. They wanted to own the land they had worked for generations. Luzon, with the country's highest rate of land tenancy, provided an ideal recruiting ground for the movement.

A quick handshake between President Manuel Roxas and General Douglas MacArthur, 1946During the inauguration of the Third Republic of the Philippines, President Manuel Roxas shakes the hand of General Douglas MacArthur of the United States of America. July 4, 1946. ORGANIZATION FOR THE INSURRECTION At the onset of the insurrection, the Huk movement was made up of three general types of people -- politicals (communists and socialists), former wartime guerrilla fighters, and a small criminal element of common thieves and bandits. Taruc would have preferred to avoid association with the latter group, but reality dictated that he accept help and recruits from whatever source. Several years later, after the government organized an effective anti-Huk campaign in late 1950, this diversity severely hurt the organization's cohesion and effectiveness. The Huks were also divided along functional lines, that is, the organization was composed of fighters, supporters, and a mass civilian base. At the heart of the movement were the regulars-full-time fighters who conducted raids, ambuscades, kidnappings and extortion. The second group of Huks, the supporters, were divided between what may be called combat and service support activities. The combat support Huks were generally "die hard" followers who joined the regulars from time to time, but usually remained in their villages and carried on life as farmers. Those considered service supporters performed such non-combat duties as collecting taxes and acting as couriers -- a most important function for the organization. Finally, there was the largest

These were the mountains used as hideouts by the NPA. Beginning in 1951, however, the momentum began to slow. This was in part the result of poor training and the atrocities perpetrated by individual Huks. Their mistreatment of the peoples made it almost impossible for them to use the mountain areas where the town people lived, and the assassination of Aurora Quezon, President Quezon's widow, and of her family by Huks outraged the nation. Many Huks degenerated into murderers and bank robbers. Moreover, in the words of one guerrilla veteran, the movement was suffering from "battle fatigue." Lacking a hinterland, such as that which the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) provided for Viet Cong guerrillas or the liberated areas established by the Chinese Communists before 1949, the Huks were constantly on the run. Also the Huks were mainly active in Central Luzon, which permitted the government to concentrate its forces.group of all, the mass support base. Although the people in this category rarely fought with the guerrillas, they provided them with food, information, and sanctuary. The number of supporters in the mass base was always a subject of either debate or boasting, but it was generally accepted to have peaked at the end of 1950 at some one million peasants and farmers. This was the foundation upon which Taruc built his movement and without which it could not have survived.11 To control far-flung Huk activities, Taruc developed an extensive and well organized structure. This structure drew heavily on wartime organization and fully integrated the militant Huk forces with the political CPP faction. The National Congress and the thirty-one member Central Committee, so common to communist movements, sat atop the organization. An eleven-member Politburo was subordinate to the Central Committee and provided day-to-day direction for the movement through its secretariat. Consisting of four major departments, the Secretariat was the level at which the movement's political and military branches met and may be considered the Huk operational level of command, with those levels above it working at the strategic level.

marking a Huk target with a smoke bomb from a spotter planeRamon Magsaysay was appointed Secretary of National Defense by President Elpidio Quirino, on August 31, 1950. The internal organization of the Huk Military Department was constructed similar to that of the overall body. Each Regional Command (Recco) was composed of a single regiment (almost totally concerned with administration and logistics) made up of two battalions of two squadrons each. The 100 man squadron (company) was nominally composed of two platoons, each platoon having four twelve-man squads.12 Despite this impressive organization, the movement suffered from two important deficiencies that worked to its detriment after 1951. These areas were armaments and communications, with armaments being the more pressing and constant problem. As during World War II, obtaining sufficient amounts of arms and ammunition remained a major obstacle.

Maria Aurora "Baby" Quezon arrives for the Independence Ceremony of 1946Maria Aurora “Baby” Quezon, eldest daughter of the late President Manuel L. Quezon, arriving for the Independence Ceremony of July 4, 1946. That’s Presidential Aide Jacobo Zobel meeting her. What weapons they had, they stole, found, or purchased in Manila's black market. To counter this shortcoming, Taruc relied heavily on obtaining weapons after battles, raiding government outposts, or simply picking up armed fighters on their way to a large engagement that occasionally saw Huk combat formations as large as 2,000 troops.13 There exists little evidence to substantiate claims made by President Roxas that the guerrillas received external arms shipments from Chinese communists on the mainland. On the contrary, the matter of arming his available troops remained one of Taruc's chief concerns throughout the insurrection. The other area in which Huk organization was deficient was communications. Although the insurgents acquired several radios during the course of the rebellion, including some purchased in Manila in 1948 but captured by government forces before they could be used, evidence showed that they were used primarily for intelligence gathering.14 That is, Huks monitored government troops but did not use the radios for their own communications. They chose to do this for several reasons; they lacked trained radiomen, sufficient radios, or spare parts and batteries. Instead, Huks relied on the time-tested courier system to transfer information, orders, and supplies between their elements. This simple system worked well for several years, supplying squadrons with information about government movements and food but, lacked flexibility and responsiveness when later faced with new government tactics. Huk Intelligence and PSYOP During the height of the insurgency, much of its success depended on good intelligence. Outnumbered, outgunned, and outsupplied, Taruc relied on information about government activities to plan his operations. Throughout Huklandia, his agents recruited local government officials and members of the Philippine Police Constabulary as informants. Not all of these officials offered their help voluntarily, but threats against them or their families often gained their cooperation.15 Huks also attempted, sometimes successfully, to infiltrate government forces. Once in, agents sought weapons, information, and provoked ill feelings between officers and men by pointing out how differently were their respective life styles within the armed forces. Police and several Philippine Army officers and men collaborated by providing information, either to prevent trouble in their area of responsibility or for greed.

Post War Manila, Philippines. Santo Tomas University and campus. Picture was taken from the main UST building looking south-west.The building with the dark-colored upper half is the old Avenue Theater on Rizal Avenue. The tower-like structure in front of it is part of the Bilibid Prison on Azcarraga (CM Recto now). Also faintly visible in the distance is the Hotel Great Eastern on Echague, once the tallest structure in Manila. During the early years of the insurgency, before 1951, Taruc found that good intelligence information was not hard to gather. Peasants were eager to help the Huks fight the government troops, who often treated the villagers worse than did common bandits. Information was transported up through the Huk or CPP organization via couriers. The couriers, either "illegals" (usually young, innocent looking men and women who traveled cross-country) or "legals" (couriers that used the highway and public transportation networks) passed their messages on at established relay points to the next courier. Knowing only two points of the entire system (their individual start and finish points), the couriers proved highly successful and remarkably secure until well after 1951. The occasional government radio that fell into guerilla hands also provided a wealth. of information about AFP and police operations. In fact, it was one of these captured radios that led to the 1949 Huk ambush and killing of Senora Aurora Quezon, wife of the former president--an incident that proved a grave miscalculation. The Huks were always quick to adapt local concerns into effective propaganda campaigns. The original slogan, "Land for the Landless," was catchy, to the point, and served the Huks well for many years. Following the violent and fraud-ridden 1949 election, Taruc adopted a new slogan for the movement--"Bullets, not Ballots." Again, Huk leaders identified a situation that the people felt strongly about and capitalized on it.

To supplement their propaganda campaign and to prove to the people that the Huk/CPP organization had authority, Huk headquarters published and widely distributed a series of newspapers and periodicals. These publications ran the gamut from the bi-weekly newspaper Titus (Sparks) to a monthly theoretical magazine for Huk cadre, Ang Kommunista. There was also Mapagpalays (Liberation), a monthly periodical that dealt with the Huk struggle and its goals, and a cultural magazine, Kalayaan (Freedom), that published short stories, poems, and essays. Huk propagandists also experimented with correspondence courses, producing two self-study pamphlets with monthly updates -- one for Huk regulars, and one for CPP political workers. Taruc and the Huk leadership used poor social conditions and corruption within government to fuel their propaganda campaign. During 1948, and up until the general election of 1949, the Huks devoted great efforts to publicize examples of governmental excess and corruption.

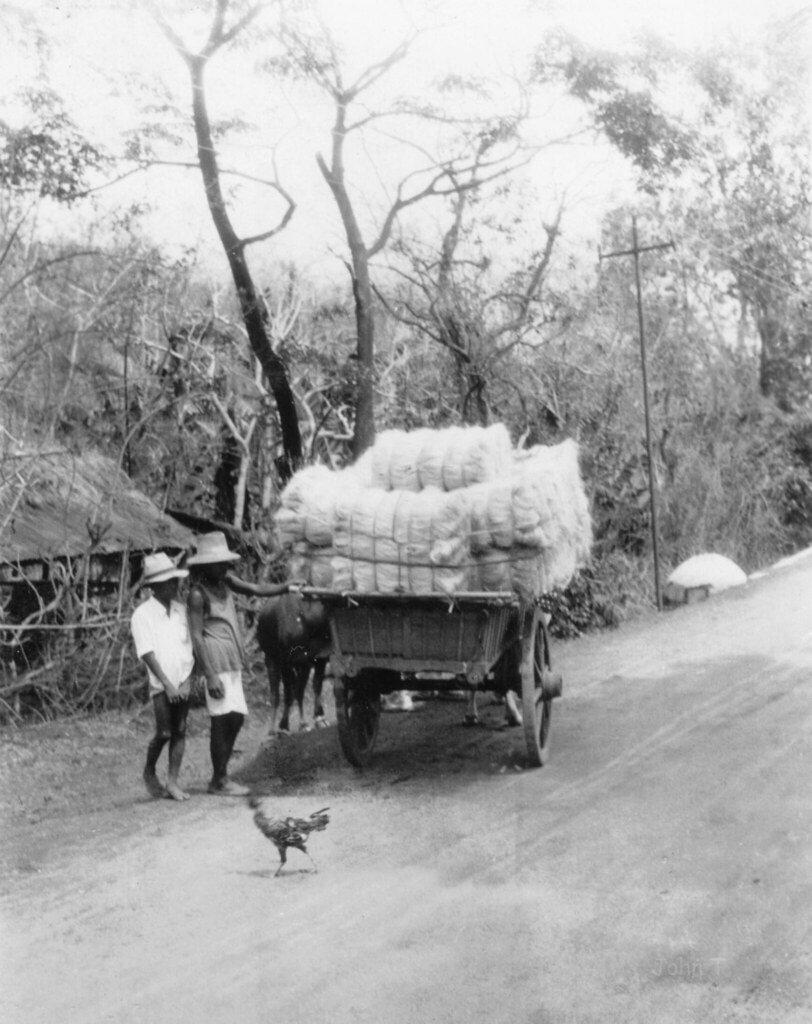

FILIPINO FARM HOME LUZON PHILIPPINESFor example, in 1948 a full 75 percent of Luzon's population were peasants and, for these people, the postwar government had done little to mitigate their plight.20Tenancy had returned, landlords ignored laws that established debt ratios for the farmers, and the courts invariably decided in favor of influential landlords. The gap between the Philippine upper classes and the peasant majority had widened since the war and independence, not contracted as many had hoped.

EVERYDAY LIFE, LUZON, PHILIPPINESGraft and corruption ran rampant in government. The Roxas administration seemed to condone it and did nothing to conceal its presence or depth. In a 1948 letter to General Omar Bradley, the Chief of Staff, Major General George F. Moore (Commander, U.S. Army Philippine-Ryukyus Command) reported that Philippine law enforcement and court systems were, inadequate, applied arbitrarily, and did not protect the citizen. Rather, he reported they were being used as tools by government officials, wealthy landowners, and businessmen. General Moore cited an investigation into a criminal ring involved in stealing U.S. surplus jeeps and selling them on the black market. Sons of the mayor of Manila, the Police Chief, and the Secretary of Labor were implicated as running the ring and of ordering the murder of an American investigator's infant daughter. Local police in San Luis confessed to taking part in the incident, and testified that the town mayor, Atilio Bondoc, fired the shot that killed the little girl. Local courts found the policemen guilty and gave them light sentences, but the mayor was released without action.

Everyday life, Luzon, PhilippinesGeneral Moore also connected this criminal ring to the killing of a U.S. officer outside a supply depot in Manila and with discrepancies in the Philippine Foreign Liquidation Commission's books. The Commission, composed jointly of American and Filipino administrators, was established to oversee the disposal of surplus equipment in the country. At the time Moore wrote Bradley, there existed a shortage of some 6,000 jeeps that should have been accounted for in Commission records. When confronted with the evidence, the Commission failed to take any action. This corruption also extended into gasoline, hijackings of U.S. cargo trucks, spare parts, and incidents of U.S. equipment being thrown off moving trains to waiting thieves. Finally, when some culprits were brought to justice, the General found that they were either acquitted or given light fines and released.22 These were examples of corruption and government sponsored crime that Huk propagandists ensured went before the "public's eye."

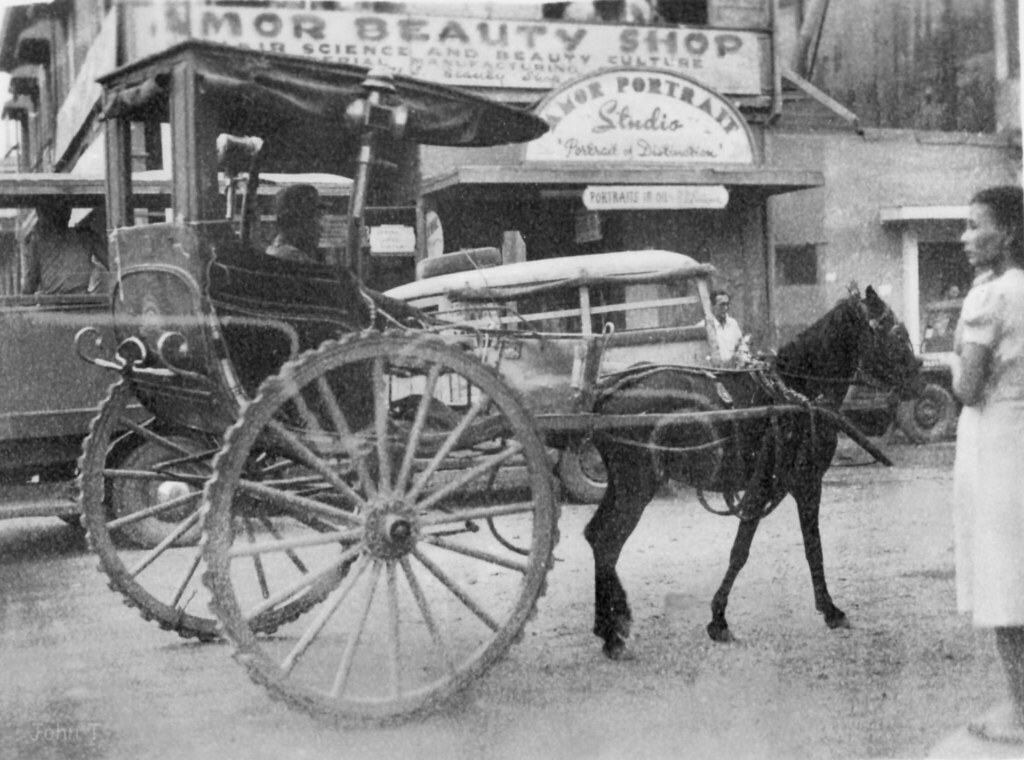

Calesa on street in front of Amor Beauty Shop and Portrait Studio after 1945 before 1950The signs read: Amor Beauty Shop, Hair Science and Beauty Culture, Amor Portrait Studio, Portrait of Distinction, Portraits in oil. Huk Financing and Logistics The widespread Huk structure required an extensive logistics system to support the guerrilla fighters as well as CPP political activities. Since Taruc received little if any outside aid or equipment, he relied on local support and the Manila based National Finance Committee. In and around Huklandia, the Huks levied quotas on villages for food and some money. Villagers unsympathetic to the cause were intimidated into making contributions by specially organized tax collectors -- toughs and thugs. Collections were augmented by Huk agents who impersonated government tax collectors in areas not under their control and by occasional raids, holdups, or train robberies.23 In Manila, the National Finance Committee organized a series of Economic Struggle Units to gather funds and equipment. These units collected voluntary contributions, mainly from the 20,000 Chinese living in and around Manila, and conducted urban robberies, extortion rackets, and levied taxes in Manila's suburbs. Collected funds were divided equally between the Huk/CPP national headquarters and the local regional command (Recco). To supplement food received by local sympathizers, Huks began to establish "production bases" in 1948. These "bases" were actually small farms run by Huks and protected from the government by their dispersed locations within Huklandia. The bases only became vital once the Philippine Army severed Huk logistic routes during and after 1951. Weapons and ammunition posed a constant supply problem for the insurgents. There were never enough of either to go around and lacking outside assistance, Huks had to make do with weapons left over from the war, captured from the Army, or stolen from U.S. military depots intended for the invasion of Japan. However, showing the greatest of confidence in the solidarity of the international communist movement, Taruc established a secret base on Luzon's Pacific coast to receive clandestine arms shipments from submarines.25 As best as can be determined, this base was never used and the Huks were forced to fight the battle with old Enfield and Springfield rifles, carbines (some of which were converted by Huk ordnance shops into fully automatic weapons), .45 caliber "tommy-guns", a few .30 caliber machineguns, and small mortars, normally no larger than 60 mm. HUK MILITARY OPERATIONS Throughout the first phase of the insurrection, 1946-1950, Huk squadrons roamed freely across central Luzon harassing Philippine Army and Police Constabulary (PC) outposts at will and gaining support. The poorly led, underpaid government forces, with a combined total strength of only 37,000 in 1946, faced 56 10,000-15.,000 Huk regulars and over 100,000 supporters in a region of two million inhabitants.26 Following the first engagement between Huks and government forces (shortly after Manuel Roxas was inaugurated in May 1946), the tendency among government troops was to remain close to the campfires.27 On those few occasions when these forces ventured afield and encountered Huks, the outcome usually favored the insurgents. Having been ceded the initiative by the government, Huks seized town after town, establishing martial law and spreading their influence as they went. In the first battle between government regulars and the guerrillas, a Huk squadron ambushed a 10th Military Police Company patrol in the town of Santa Monica in Nueva Ecija Province. Ten members of the patrol were killed and the patrol leader captured and beheaded. The Huks did not lose a single man in the engagement and the victory provided the fledgling Huks with a tremendous boost in morale. The Santa Monica ambush was followed quickly by other hit-and-run raids on Army patrols and outposts. Huk recruitment showed a dramatic increase because of these early military victories. Events that began in Santa Monica culminated when Huk Commander Viernes, alias "Stalin," captured the city of Nueva Ecija, the provincial capital, with 200 Huk regulars, and declared it Huk territory.28 This overt challenge to the government went unanswered for years. 57 While coordinating activities with Taruc's fighters, the CPP began to expand rapidly in the fall of 1946. As political influence spread. westward from the central plain into Bataan and Zambales provinces, propagandists were followed closely by organizers and Huk forces. This was the Huk pattern -- to follow political agitators with Huk organizers and then establish the area as their own with HMB squadrons. Within a short time they exerted considerable political and military influence in Pangasinan Province to the north; in Nueva Vizcaya and Isebala; in Laguna, Batangas, and Tayabas provinces in southern Luzon; and on the island of Panay.29 Despite an occasional military setback during this phase of the insurrection, Huks worked constantly to build bonds with the people. Many times, squadrons would stay with villagers, working and playing with them, all the while developing stronger ties and indoctrinating them about the Huk/communist cause. Army forays against the insurgents usually caused few guerrilla casualties but often resulted in the frustrated soldiers taking vengeance on the local people. Military Police Command terrorism and constant demands from the soldiers for food and supplies, bolstered Huk claims that they, not the government, were trying ;to protect the people from abuse and lawlessness.30 Huk raids continued through the spring of 1947, steadily increasing in size and number. In April, the insurgents ambushed an Army patrol, killing six men. In May, a hundred-man squadron attacked the garrison at Laur, Nueva Ecija, looted the village bank and kidnapped the local police chief, who they held for ransom. At the same time, raids and ambushes took place in San 58 Miguel, in Bulacan, and in other provinces across central Luzon.31 President Roxas was outraged by the Huks' success and following the Laur raid, ordered the military to attack the guerrilla stronghold around Mount Arayat. Two thousand Army and constabulary troops participated in OPERATION ARAYAT. The operation spanned two weeks but produced only meager results -- twenty-one Huks were reported killed in action and small quantities of rice and weapons captured. Huk intelligence agents knew the government troops were coming, where they would be coming from, and about how long they would devote to the operation. As a result, almost all the Huks in the area slipped through government lines to safety. When contact was made, it usually happened by accident, thus the relatively low Huk losses considering the total number of insurgents in the affected area.32 In February 1947, Luis Taruc outlined his "five minimum terms for peace" to author and journalist Benedict Kerkvliet. Taruc demanded that the government: immediately restore individual rights; grant amnesty for all Huk members; replace police and government officials in central Luzon; restore the seats of the six Democratic Alliance congressmen elected in 1946; and institute land reforms that would abolish land-tenancy.33 Taruc realized fully that Roxas would never concede to these demands, especially those concerning the DA congressmen and replacing officials but, the Huks were riding a swell of popular support and proclaiming the movement's demands gave it credibility outside central Luzon. 59 Huks felt so secure within Huklandia that, by 1948, training camps, command bases, schools, and production bases were reestablished across central Luzon, much as was done during World War II.34 With its center at the 3,400 foot tall Mount Arayat, the Huk stronghold spread south across the marshy and seasonally flooded Candaba Swamp, east to the Sierra Madre mountains, and west to the mountains of Zambales province.35 As they solidified control over this broad area, the Huks increasingly integrated military and political/cultural activities to cultivate links with the towns and villages. If Taruc's movement was to succeed in the eventual overthrow of the government, he had to have a firm and resolute popular base from which to act.

Ninoy Aquino receives his first Legion of Honor awardAugust 1951: Eighteen-year-old Benigno S. Aquino Jr. receives the Philippine Legion of Honor with the rank of Officer, for his service in reporting on the state of the Philippine troops in Korea. Standing beside him is Defense Secretary Ramon Magsaysay, who will soon hire the young Ninoy as an aide. President Roxas died unexpectedly of a heart-attack while visiting Clark Field in April 1948. Upon hearing the news, Taruc made clear his feelings about both Roxas and the United States when he eulogized the former president as "(dying) symbolically in the arms of his masters .... His faithful adherence to American imperialist interests and the excessive corruption in his government had exposed him to the people."36 His successor, Elpido Quirino, was more moderate on the issue of the Huks, and after declaring a temporary truce, opened negotiations with Taruc and Alejandrino for the surrender of Huk weapons. After four months of negotiations, during which time both sides violated the truce numerous times, the talks broke off. Taruc returned to the mountains on 29 August 1948 and rejoined his forces. Although Taruc blamed the failed talks on Quirino's bad faith, there was really no valid reason for the Huks to surrender -- they were beating government troops in the field and expanding their support base almost at will. Taruc used the four months to reorganize and strengthen his position in Huklandia, establish new arms caches, and use public gatherings to spread propaganda and incite the crowds against the Quirino government. 1948 proved a difficult year for Huk political /military cooperation. The Politburo, now under the leadership of Jose Lava, wished to pursue the Russian model of class struggle by concentrating on urban centers and disrupting government activities to bring about the communist overthrow. The Huks however, under Taruc, were more Maoist in outlook and, based on its peasant base, wanted to expand its rural base and continue the fight in the countryside. The argument over where to concentrate Huk efforts caused a rift within the organization. Although the rift did not prove fatal to either camp, it reduced the effectiveness of both the CPP Marxist-Leninists and the Huk Maoists. Furthermore, when the tide of battle turned to favor the government after 1950, old scars caused by this dissention opened once again and helped to bring about the end of the entire movement. In November, the military wing of the movement changed its name to the Hukbong Magapalaya ng Bayan, the People's Liberation Army, commonly referred to as the HMB. Drawing on the support garnished during the summer truce, the HMB started a new series of raids on government troops and targets. Throughout the following year, 1949, HMB raids continued against government installations in and around central Luzon. Most of the raids were typical guerrilla operations, hit-and-run, and were usually conducted at night to avoid direct confrontation with AFP forces. Despite their numerous ambuscades and raids on banks and supply depots, the HMB did not participate in the old guerrilla favorite - sabotage. This was not only because they lacked trained demolition men or equipment, but also because the Huks relied heavily on government transportation and communication facilities for their own purposes.38 The Huk campaign that began in November 1948 reached its peak in April 1949, with the ambush of Senora Aurora Quezon, widow of the former Philippine president. Commander Alexander Viernes, alias Stalin, took two hundred men and laid an ambush along a small country road in the Sierra Madres mountains and waited for a motorcade carrying Sra. Quezon, her daughter, and several government officials. When the ambush ended, Senora Quezon, her daughter, the mayor of Quezon City, and numerous government troops lay dead alongside the road. Although Viernes claimed a great victory, people throughout the islands, including many in central Luzon, were outraged. Viernes misjudged his target's popularity. President Quezon left a strong nationalistic sentiment after his death in exile during the war, and his widow represented the spirit of Philippine nationalism and resistance.

Maria Aurora “Baby” Quezon, before the Independence Ceremony of 1946 beganMaria Aurora “Baby” Quezon, seated in the Quezon box to view the Independence Ceremony of July 4, 1946. Feeling the swell of popular indignation about the death of a national hero's wife and family, Taruc denied responsibility and said that the ambush was conducted without HMB approval. Despite his attempts to disclaim the actions of an overzealous Commander Viernes, Taruc lost a great deal of popular support and confidence over the incident, confidence he never fully regained and support that he would need later, but would not find forthcoming.39 Huk political organizers took full advantage of conditions that accompanied the 1949 general election. In a race that pitted Jose Laurel, the Nacionalista Party candidate and former president under the Japanese occupation, against Quirino, the incumbent Liberal Party candidate, the Huks seemed to enjoy the violence and mud-slinging that had become part of Philippine politics. Each new charge raised by one candidate against the other provided new ammunition for the Huk cause. The Politburo finally decided to support Quirino, the more liberal of the two candidates, and ordered the organization to work for his election. Huk goon-squads joined those from the Liberal Party and battled similar "political action groups" from the opposition for control of the election.

President Sergio Osmeña and President-elect Manuel Roxas leave Malacañan Palace, en route to the latter’s inauguration, May 28, 1946The departure of the incumbent President, accompanied by the President-elect, marks the formal act of leaving office for the incumbent, who descends the stairs of the Palace for the last time. For further reading on this ritual On election day, thugs from both sides intimidated voters at the polls, ballot boxes were stuffed or disappeared mysteriously, and in more than one province the number of ballots cast far outnumbered the entire population.41 Quirino won a slim victory, but at the cost of widespread popular despair about Philippine democracy. Many of the disillusioned turned to the communists as being the only hope for reducing corruption, violence, and the disregard for individual rights that had become ingrained in society. Aided greatly by the horrible conditions that accompanied the 1949 election, Huk strength and influence grew by the end of the year, recovering somewhat from the Quezon ambush episode. HMB regular strength grew to between 12-14,000 and Taruc could rely on 100,000 active supporters in central Luzon. After the elections (fraught with fraud, terror, and rampant electioneering violations), Huk raids became more frequent and widespread. A Huk squadron occupied the town of San Pablo; Police Constabulary posts at San Mateo and San Rafael were attacked and the towns looted; and the mayor of Montablan was kidnapped and held for ransom.42 After most of these attacks, Huks left propaganda pamphlets with the people seeking their aid and support, and playing on their growing sense of disaffection for the government that resulted from election fraud. As the guerrillas strengthened their control in Tarlac, Bulacaan, Nueva Ecija, and Pampanga provinces, most government officials left their offices every day before nightfall, returning to the relative safety of homes they maintained in Manila. Supporting communist claims, the election was a signal from the administration for corruption to run amuck. All forms of government permits and contracts were bought and sold openly, while favoritism and nepotism spread rapidly throughout the government.44 Bolstered by new supporters that governmental policies provided, and against a backdrop of near governmental collapse into fraud and corruption, the Huk Politburo declared the existence of the "Revolutionary Situation" in January 1950, and called for the beginning of the armed overthrow of the government. Jose Lava, the political leader of the CPP, advanced the communist timetable for the overthrow of the Philippine government by approximately two years and was met with immediate and harsh criticism from Taruc. Although Lava saw the situation favoring increased communist initiatives for military actions, political expansion, and mobilization of the, masses, Taruc did not. Rather, Taruc felt it premature to attempt the overthrow and desired to maintain the original agenda and limit activities to guerrilla operations and the expansion of their popular base. The two leaders could not reconcile their differences and, in late January, Taruc broke ranks with the CPP dominated political wing of the movement. Undoubtedly, part of this rift was a result of long-standing political differences between the CPP from the HMB. As was the case surrounding an earlier rift between the two in 1948, the CPP tended to follow Marxist-Leninist strategy while Taruc and his HMB were more inclined to adhere to Maoist theory based on peasant revolt. Following the split, Taruc and the HMB continued to carry-on the guerrilla campaign against the Quirino government with almost daily raids across central Luzon. Attacks spread to both the north and south of the central plain and outlying districts of Manila were no longer spared from guerrilla intrusions. Even small Philippine Army outposts, usually avoided in the early years of the insurrection, now joined PC barracks on the Huk target list.

President Manuel Roxas arrives for the Independence Ceremony of 1946President Roxas is flanked by his wife Trinidad de Leon Roxas and Mrs. Aurora Aragon Quezon, widow of the late President Manuel L. Quezon, and followed by the President’s son, Gerardo M. Roxas. As the attacks increased to some ten times their pre-1950 frequency, President Quirino abandoned his conciliatory stance toward the rebels. In a last-ditch effort to stop the insurgency, he ordered the armed forces to assume the responsibility for combatting the insurgents and to return to the terror tactics that the Roxas administration had once used so 65 widely. Quirino's change of heart, taken out of pure frustration, did little to hinder Taruc's operations but did manage to remind the people why they had shifted their support to the Huks in 1946.46 In response to renewed AFP/PC terror and intimidation tactics, the Huks also reverted to this most base form of warfare, leaving bodies in streets with tags on them that read: "He resisted the Huks." In one case they quartered a Catholic priest before a group of his parishioners who had assisted government forces.47 Attacks against three major cities by squadron sized or larger units took place in May, and were followed in August, by a series of large-scale attacks directed against Army barracks. On 26 August, two simultaneous attacks were launched against garrisons at Camp Macabulos (in Tarlac) and at Santa Cruz (in Laguna), involving no less than 500 Huk regulars. At Camp Macabulos, two squadrons killed twenty-three army officers and men and seventeen civilians before releasing seventeen Huk prisoners and burning and looting the camp's storehouse and hospital. Meanwhile at Santa Cruz, three hundred Huks sacked and looted the town, killed three policemen and fled to Pila in stolen vehicles before government reinforcements could be mustered.48 These attacks were examples of the first of three varieties of raids that Taruc planned to carry-out against the government-- organized assaults. The second variety, terror raids, were conducted by smaller formations against undefended cities and barrios, with the intent of killing government officials and intimidating the populations. Finally, Taruc planned to conduct 66 nuisance raids -- small ambushes, roadblocks, or hijackings that would harass government forces and demonstrate Huk control over certain regions. These attacks were usually planned to coincide with national festivals or fiestas, when security would be lax or, during the rainy season when weather conditions would favor hit-and-run tactics by his HMB that now numbered 15,000 regulars (with 13,000 weapons), 100,000 active supporters, and a popular base estimated to number nearly a million peasants in central Luzon.49 While Taruc's HMB forces increased their military pressure on the government, Lava ordered party activists to increase the tempo of their activities to ease the path for the armed revolution -- a revolution that the Politburo estimated would topple the Philippine government in 1951.50 These grandiose plans; calling for a total Huk force of some thirty-six divisions that would have 56,000 cadre, 172,000 party members, and a mass base of 2.5 million supporters; fell apart quickly when the. Politburo was unexpectedly captured by government troops in October 1950.51 ARMED FORCES OF THE PHILIPPINES OPERATIONS In 1946, the Armed Forces of the Philippines consisted of only 25,000 poorly trained, armed, and led troops scattered throughout the islands. The AFP was the remains of the war-time 67 Philippine military and police forces, reduced rapidly after the war from their former strength of some 132,000.52 The Philippine Military Police Corps was the result of General MacArthur's authorization to form thirteen military police companies, armed as police, to maintain internal peace and order.53 In addition to the Army and MPC forces, the government had a small Navy (some 3,000 sailors), and an equally small and outdated Air Force (only 3,800 men). Other than participating in a few resupply missions, the Air Force did not play an important role during the initial phase of the insurrection. After 1950, the Air Force role increased in size and function as it assumed a larger part of the overall anti-Huk campaign. In Manila, the government treated the Huk problem as simply a series of criminal acts, not an organized and well established insurrection. President Roxas vowed to attack the guerrillas with a "mailed fist" but, except for independent forays by ambitious local authorities and a few military police units, the mailed fist was stuffed with cotton. When the government mounted operations against the Huks, it seldom succeeded in anything but alienating the local villagers who felt the brunt of the troops' frustrations.54 Roxas seemed more amenable to seeking the spoils of office for himself and his followers than to fighting Huks on their homeground. In June 1946, Roxas admitted the futility of his plan to "exterminate" the guerrillas and attempted to negotiate an agreement with Taruc. Promises of agrarian reforms in exchange for the surrender of weapons were broken and negotiations ceased. 68 The government returned to its policy of haphazard operations in central Luzon, but with no better results than it had had before the truce. Government forces stayed close to their barracks and bands of "Civil Guards" (private armies hired by landlords), tried to protect plantations and went on occasional, and always unproductive, "Huk hunts." After the November elections, both sides reduced military activities to consolidate and reorganize. The Army was exhausted from futile dashes into the swamps and mountains and needed the time to train with weapons they were receiving from U.S. stocks of surplus World War II arms. By January 1947, Roxas, always keen to improve his political standing, took advantage of the relative calm and declared the situation solved. His declaration was soon met by a resurgence of activity centered in Huklandia.55 Embarrassed over his premature declaration, Roxas ordered a major offensive in March, 1947. In the largest and most organized government effort since the end of the war, three battalions of regular forces and military police units advanced into the area around Mount Arayat. Accompanied on the expedition by numerous newspaper reporters, food vendors, and sightseers, the two thousand government troops waded ever so slowly into the Huk stronghold. Although they managed to capture about a hundred insurgents, the operation did not damage Taruc militarily -- it merely made him more cautious and showed him that he needed a better intelligence organization.56 Following this offensive, Roxas dismantled the Military Police Command and formed the Police Constabulary (PC) in its stead, with the mission to provide internal security for the country and to perform other police-style functions. The Constabulary was organized into ninety-eight man companies with from one to fifteen companies 69 assigned to a Provincial Provost Marshall depending on the size and location of the province. In turn, the Provost Marshall worked directly for the Provincial Governor.57 In March 1948, after the collapse of another brief truce, Roxas declared the Hukbalahap illegal and announced that he was putting his "mailed fist" policy back into effect. Company after company of constabulary troops charged into Huklandia burning entire villages, slaughtering farm animals, and killing or imprisoning many innocent peasants in their search for the elusive insurgents.58 They located few Huks, killed or captured even fewer, and alienated almost the entire population of the region from the central government. Shortly after Roxas' death in April 1948, President Quirino offered the Huks another chance to negotiate a settlement. As was the established pattern for these truces, the negotiations proved fruitless but the Huks put the months of government inactivity to good use by increasing their internal training and organization.

Haying in the fieldsWhen this truce finally broke-down, Quirino was forced to acknowledge that the insurgency was indeed a major problem, one too large for the constabulary to handle alone. To alleviate this shortcoming, he assigned one regular army battalion, the 5th Battalion Combat Team (BCT) to the PC.59 Two years later, after the 5th BCT was badly beaten in an engagement with the guerrillas, Quirino reorganized the constabulary under the Secretary of National Defense, removing it from the 70 jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Interior where it had languished since 1945. "Force X" Shortly after the Secretary of National Defense reorganized the constabulary, the government authorized the one truly successful anti-insurgent operation during the first phase of the insurrection -- "Force X." This special force was envisaged to operate deep within enemy territory under the guise of being a Huk unit itself. As such, the force would be valuable in obtaining intelligence and carrying out small unit operations such as kidnappings of Huk leaders and ambuscades. "Force X" was created to take advantage of a period when Huks operated freely in central Luzon but when their command organization was loose and inexperienced.60 Philippine Army Colonel Napoleon Valeriano, commander of the Nenita Unit, a special constabulary force that operated in the area of Mount Arayat from 1946 until 1949, selected the 16th Police Constabulary company, under the command of Lieutenant Marana to become "Force X". Secretly screening his unit for the most devoted and aggressive men, Marana selected three officers and forty-four enlisted men who departed their barracks under the cover of darkness and moved to a secret training camp in the nearby jungle. The camp's location and purpose were known only to the president, the Army Chief of Staff, Col. Valeriano, and three of the president's closest staff officers. At the camp, the unit was stripped of issued clothing and equipment, and given captured weapons and old civilian clothes. Using three captured guerrillas as instructors, "Force X" received training in Huk customs, practices, and tactics to help them pass as the enemy. 71 Each man assumed an alias as well as a nickname, a technique favored by the Huks, and began to live life as a guerrilla.61 After four weeks of intensive training and a careful reconnaissance into the area where "Force X" would initially venture, the unit was almost ready to go. To complete the scenario, Colonel Valeriano recruited two walking-wounded from an Army hospital in Manila and secretly transported them to the training camp. At 1700 hrs, 14 April 1948, "Force X" fought a sham battle with two police companies and withdrew with their "wounded" into Huk country. Four hours later they were met by Huk troops, interrogated as to who they were and where they had come from, and were taken into Candaba Swamp where they met Squadrons 5 and 17. Marana convinced the commander of his authenticity (a story based on the death of a genuine Huk leader) and was promised that he and his forces would be taken to Taruc. The cover was working better than expected.62 "Force X" spent two days at the base-camp learning a great deal about local officials, mayors, and police chiefs who were Huk sympathizers and about informants within the constabulary. As they awaited their appointment with Taruc, they were joined by two other squadrons, one of which was an "enforcement squadron" whose members specialized in assassination and kidnapping. On the sixth day in camp, Marana became suspicious of Huk attitudes and ordered his men to prepare to attack the assemblage. Quietly removing heavy weapons (including four 60mm mortars, two light machine-guns, 200 grenades, and a radio) from hidden compartments in their packs, "Force X" attacked the unsuspecting squadrons. 72 In a thirty-minute firefight, "Force X" killed eighty-two Huks, one local mayor, and captured three squadron commanders.63 After radioing for reinforcements to secure the area, "Force X" took off on a two week long search and destroy mission, accompanied this time by two infantry companies. During seven engagements, government troops killed another twenty-one guerrillas, wounded and captured seven, and identified seventeen Huks in local villages. "Force X's" success did not stop when it withdrew at the end of the operation. Three weeks after the incident at the Huk base-camp, two squadrons stumbled onto each other and, each assuming that the other unit was "Force X," opened fire. The panic and mistrust that "Force X" put into Huk ranks cost the insurgents eleven more dead from this chance encounter.64 AFP Tactical Operations Unfortunately, "Force X" was practically the only bright spot for the government during 1946-1950 and it was fielded too infrequently. Most other operations remained bound to conventional tactics involving large units. Task forces continued to be ordered out only following some Huk victory or atrocity that made political waves in Manila. Even when an operation reached its announced objective, follow-up operations were rare and troops usually returned immediately to garrison. These conventional sweeps proved ineffective and left many other areas totally bare of government troops. As a final detriment, most of the large operations harmed civilians more than the guerrillas. This did very little to develop feelings of 73 confidence or allegiance between the people and their central government.65 Poor tactical leadership, slow responsiveness, slipshod security, and inadequate logistic support characterized the majority of military operations during this period. Troops were forced to live off the land, or rather, to live off the villagers. Enlisted men lacked discipline while their officers, often engaged in large-scale corruption themselves, did little to correct the situation. Although these officers were often implicated in Manila-based scandals, Army leadership did nothing. Throughout 1948, the Philippine military remained ineffectual in Luzon's central plain. What little progress took place was instigated by President Quirino on a political level through negotiations with Taruc. For a brief time, Quirino returned Taruc's congressional seat and back-pay, but after months of debating and public denunciations from both sides, Taruc rejoined his guerrillas in the mountains in August to resume the fight.67 His return to the countryside produced increased government actions that hurt relations between the people and the largely out-of-touch and uncaring central government. Government forces changed little during 1949 with the exception that the Police Constabulary grew modestly in size. However, whatever increased effectiveness that could have been achieved from this expansion was lost when the police companies were broken into platoon sized units and scattered across the nation - in essence, losing their numerical and equipment advantage to the Huks, still concentrated in central Luzon. Too often, these new constabulary units were used solely to administer local law, serve warrants, and try to keep the peace in "their" village. This led to a tacit modus vivendi between the police and guerrillas in an area.68 Dedicated anti-Huk operations by either the Philippine Army or the Police Constabulary remained few in number and insignificant in effect with the exception of the government operation mounted after Huks murdered Sra. Quezon on 28 April.

Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña together for the last time, August 3, 1944.On the left, President Manuel L. Quezon and his Vice President Sergio Osmeña strike a pose shortly after their inauguration in 1935. Next to this is a photo of Sergio Osmeña paying his respects to his friend, Manuel L. Quezon. Osmeña assumed the presidency after Quezon’s death. He was 67 years old. Ordered by President Quirino not to return to garrison until all the Huks who ambushed Senora Quezon were themselves either dead or captured, 4,000 troops (two constabulary battalions and one army battalion) went into the Sierra Madres mountains. Divided into three task forces, one to block and two to maneuver, the force scoured the mountain-sides. After two weeks of relentless patrolling, a Huk camp was discovered and while taking it, government troops captured a Huk liaison officer who told them the location of Commander Viernes' base-camp near Mount Guiniat. Five companies converged on the mountain camp at dawn, 1 June 1949, but killed only eleven guerrillas before discovering the camp was only an outpost, not Viernes' base. The following day, government forces located the base-camp and attacked immediately. The troops captured the camp, that turned out to be "Stalin University," and in the ensuing week long search and destroy mission killed thirty-seven additional Huks. Commander Viernes, however, managed to elude the net once again. After two more months of searching the mountains, the Philippine Army cornered Viernes near Kangkong and killed him on 11 September. His death, along with the deaths of many of his captains and several other Huk commanders, ended the operation that had spanned nearly four months. All toll, 146 insurgents were killed, 40 captured, and an entire Huk regional command was destroyed during the operation.

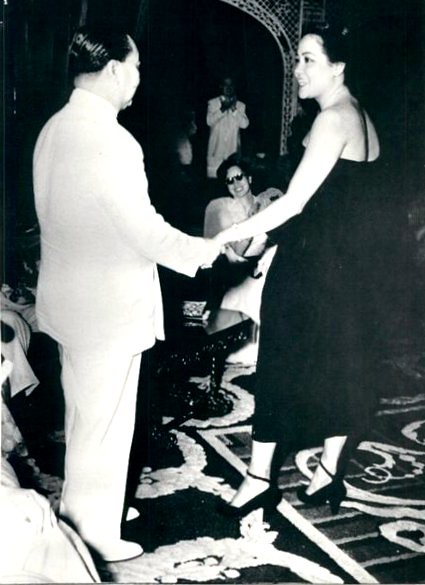

Conchita Gaston and Pres. Elpidio QuirinoFamous Philippine Mezzo Soprano Conchita Gaston Conchita Gaston, from Negros, was a vivacious dark-eyed beauty of outstanding musical ability. She made her operatic debut in the title role of "Carmen" New York City Center Opera Company. The above is an Associated Press (AP) press photo slugged: (SE1-Feb 27) -- SET TONGUES TO WAGGING -- President Elpidio Quirino, who denies romantic interest, shown here escorting opera singer Conchita Gaston to a seat at Malacanan Palace musicale in Manila recently. She sang for him two Spanish love songs causing new speculation of romance.

However, after the conclusion of the Sierra Madres offensive, conditions in the Philippine military returned to their old form of normalcy--ineffectiveness, corruption, and no efforts whatsoever to help the local villagers. Army checkpoints became "collection points" where troops extorted money from local citizens. The Philippine Chief of Staff discovered this situation when he (wearing civilian clothing) was stopped by a group of soldiers who demanded money from him. On Good Friday, 1950, army troops massacred 100 men, women, and children in Bacoor, Pampanga, and burned 130 homes in retaliation for the killing of one of their officers. In Laguna, fifty farmers attending a community dance were placed before a wall and executed as "suspected Huk." The Philippine Air Force also contributed to the government's loss of popular support. It acquired several P-51 Mustangs from the United States in 1947, and used them to strafe and bomb suspect locations. Unfortunately, these aerial raids caused more damage to civilians than to the Huks, and in mid-1950, the government placed tighter controls over the use of the fighter-bombers. In general then, government forces were treating the people worse than were the guerrillas, who while occasionally preying on a village, did try to maintain close ties with the majority of the population in central Luzon. By mid-1950 it was obvious that the Philippine armed forces simply were not holding their own against the Huks. They lacked both direction and an overall campaign strategy. Orders went directly from AFP GHQ in Manila to army units in the field. The intelligence effort was sadly lacking and no plans were in the offing to improve it. What plans were being made involved defensive operations around towns or the estates of large landowners or businessmen. The AFP was acting more as an army of occupation than as a combat force attempting to quell a rebellion. Patrols stayed close to base and invariably returned to garrison before dark. Local commanders were satisfied to continue this practice as long as their individual areas of responsibility remained out of the headlines in Manila.

President Ramon Magsaysay and General Emilio Aguinaldo at Barasoain, 1956September 15, 1956: President Magsaysay and former President Aguinaldo at Barasoain Church, on the 58th anniversary of the opening of the Malolos Congress. The Army suffered from neglected training in maneuver, communications, security, intelligence, and the use of available firepower.75 Though they tended to remain in a single area for years, local forces never gained a working knowledge of the terrain, preferring instead to stick to known paths near the base. The soldiers were often antagonistic to the local population, whom they saw as Huk sympathizers and treated accordingly. And, compounding all of these deficiencies, the soldier was poorly educated as to the purpose of the campaign. He simply didn't understand his role and therefore lacked motivation. Those above him seemed as equally unconcerned, more interested in graft, corruption, and a comfortable life than with fighting. The Philippine armed forces, numbering a total of 30,952 men in July 1950, suffered from this variety of ailments to such a degree that it almost proved fatal. The appointment of Ramon Magsaysay as Secretary of National Defense in mid-1950 helped reverse this trend.77 Faced with numerous, seemingly insurmountable problems within the armed forces, he had first to conquer these problems before he could begin his campaign against the insurgents in central Luzon. InsurrectionIn 1949, Hukbalahap members ambushed and murdered Aurora Quezon, Chairman of the Philippine Red Cross and widow of the Philippines' second president, Manuel L. Quezon, as she was en route to her hometown for the dedication of the Quezon Memorial Hospital. Several others were also killed, including her eldest daughter and son-in-law. This attack brought worldwide condemnation of the Hukbalahaps, who claimed that the attack was done by "renegade" members. [8] The continuing condemnation and new post-war causes of the movement prompted the Huk leaders to adopt a new name, the 'Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan' or the 'People's Liberation Army' in 1950. Public sympathies for the movement had been waning due to their postwar attacks. The Huks carried out a campaign of raids, holdups, robbery, ambushes, murder, rape, massacre of small villages, kidnapping and intimidation. The Huks confiscated funds and property to sustain their movement and relied on small village organizers for political and material support. The Huk movement was mainly spread in the central provinces of Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, Bulacan, and in Nueva Vizcaya, Pangasinan, Laguna, Bataan and Quezon. An important movement in the campaign against the Huks was the deployment of hunter-killer counter guerilla special units. The "Nenita" unit (1946–1949) was the first of such special forces whose main mission was to eliminate the Huks. The Nenita Force was commanded by Major Napoleon Valeriano. The Nenita terror tactics which were not only committed against dissidents but also towards law-abiding people sometimes helped the Huks gain supporters as a consequence. In July 1950, Major Valeriano assumed command of the elite 7th Battalion Combat Team (BCT) in Bulacan. The 7th BCT would develop a reputation toward employing a more comprehensive, more unconventional counterinsurgency strategy and reduced the random brutality against the civilian population. In June 1950, American alarm over the Huk rebellion during the cold war prompted President Truman to approve special military assistance that included military advice, sale at cost of military equipment to the Philippines and financial aid under the Joint United States Military Advisory Group (JUSMAG). In September 1950, former USAFFE guerilla, Ramon Magsaysay was appointed as Minister of National Defense on American advice. With the Huk Rebellion growing in strength and the security situation in the Philippines becoming seriously threatened, Magsaysay urged President Elpidio Quirino to suspend the writ of habeas corpus for the duration of the Huk campaign. Ramon Magsaysay's appointment as Secretary of National Defense in 1950 marked the beginning of the second phase of the Huk insurrection. His appointment marked the beginning of the end of Huk supremacy and initiated the effective government offensive that crushed the rebellion during the following four years. The previous chapter discussed some of the changes Magsaysay dictated for the Philippine military and detailed new initiatives taken by the JUSMAG to support his effort. This chapter examines the military actions that took place between 1950, when President Quirino was a virtual prisoner in Malacanang, and the collapse of the insurgency in 1954/55. AFP ORGANIZATION - PHASE II Although the Philippine military began to reorganize before Magsaysay became the Secretary, it was during his tenure that the Philippine military matured and refined its role and function. Each of the 1,100-man battalion combat teams was organized to reflect the change in tactics from conventional, to a, more unconventional mode that was based on small unit operations, mobility, and firepower at the unit level. Artillery and heavy mortar batteries were removed from the battalion and replaced with additional rifle and reconnaissance companies. When artillery was required for an operation, it was attached to the sector for use in that specific operation.1 The following charts show the organization of the Armed Forces of the 112 Philippines and of a typical Philippine Army battalion used as the basis for Magsaysay's anti-Huk campaign after 1950.

President Ramon Magsaysay takes a stroll across Malacañang ParkBehind him and his companions stands Bahay Pangarap—currently occupied by President Benigno S. Aquino III, the first Philippine President to use it as an official residence. The Headquarters and Service Company provided the battalion various support detachments used to augment rifle companies, coordinate support for the battalion, and in the case of the intelligence detachment, to conduct independent-operations for the battalion commander or the AFP general staff. Besides the intelligence detachment, the service company also included a medical detachment; a communications platoon, capable of establishing, and repairing radio or wire communication and equipment; a transportation platoon with eighteen cargo vehicles; a heavy weapons platoon with automatic weapons, 81mm mortars, and two 75mm recoilless-rifles, used to augment the weapons company; a replacement pool; and an air support detachment with light 114 observation helicopters and aircraft. The aircraft, usually WWII surplus L-5 artillery observation planes, provided aerial resupply and gathered intelligence information by observation or receiving "coded" messages from agents on the ground in guerrilla territory. Helicopters were used to evacuate wounded and proved a great morale builder for soldiers on long-range missions. Although the United States provided some heavy helicopters to the Philippine military, they were noisy, slow, and not employed in large numbers during the insurgency.2 With the exceptions of the S-2 section and pilots from the air support detachment, Magsaysay discontinued the old practice, of leaving a battalion in one area for extended periods. Instead, he ordered them moved periodically, leaving only the Intelligence Service Team and the pilots in the old location to assist the new, incoming unit.3 The Army found this allowed them the greatest flexibility to work closely with local police and constabulary units, while avoiding ill-feelings with the local populace. Within a BCT's defined area, companies or other smaller units were deployed to conduct independent operations, or. the entire battalion could join quickly with others into larger formations when needed.