Is THIS how Alexander the Great died? Study claims he was paralyzed but ALIVE for six days while his body was prepared for burial - because of a rare neurological disorder that began after a night of heavy drinking

- Previous theories have concluded he died from infection, alcoholism or murder

- New study concluded suffered neurological disorder Guillain-Barré Syndrome

- Researchers baffled by account his body showed no signs of decomposition

- Now believed he may simply have been papralyzed from the disease

It has long baffled historians, but the mystery of Alexander the Great's death may finally have been solved.

Previous theories have concluded he died from infection, alcoholism or murder.

However, a new study suggests he met his demise thanks to the neurological disorder Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS), which can leave sufferers paralyzed.

The illness is said to have begun after a 'drinking party,' where some reports claim he downed as many as 12 pints in one sitting - followed by another 12 the next day.

Following the party, Alexander the Great reportedly became 'unwell' and died eleven days later.

But, the new analysis suggests doctors may have jumped the gun in pronouncing his death; instead, experts now say he likely lay paralyzed - not dead - for another six days before really passing away.

This scenario could explain why it took Alexander's body a baffling six days to begin decaying after he was declared dead, despite the Mediterranean heat.

Alexander the Great's body did not decay for six days after his supposed death, leading the Ancient Greeks to claim this proved he was a god. In fact, says Dr Katherine Hall, he was paralyzed while his body was prepared for burial

WHAT IS GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME?

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) occurs when the body's immune system attacks its nervous system.

It affects around one in 100,000 people in the UK and US.

Symptoms usually start with a tingling sensation in the leg, which may spread to the arms and upper body.

In severe cases, the person can become paralysed.

The condition can be life-threatening if it affects a person's breathing, blood pressure or heart rate.

GBS' cause is unknown, but it usually occurs after a viral infection. The NHS states campylobacter infections have been known to trigger GBS.

There is no cure.

Treatment focuses on restoring the nervous system.

Source: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke In an article published in The Ancient History Bulletin, Dr Katherine Hall, a Senior Lecturer at the Dunedin School of Medicine and practising clinician, says previous theories around his death in 323BC have not been satisfactory as they have not explained the entire event.

'I wanted to stimulate new debate and discussion and possibly rewrite the history books by arguing Alexander's real death was six days later than previously accepted,' she said.

'His death may be the most famous case of pseudothanatos, or false diagnosis of death, ever recorded.

Along with the reported delay in decay, the 32-year-old was said to have developed a fever; abdominal pain; a progressive, symmetrical, ascending paralysis; and remained compos mentis until just before his death.

Only five barely intact accounts of his death at Babylon in 323 BCE survive to the present day.

None are from eyewitnesses and all conflict to varying degrees.

According to one account from the Roman era, Alexander died leaving his kingdom 'to the strongest' or 'most worthy' of his generals.

In another version, he died speechless in a coma, without making any plans for succession.Share

Only five barely intact accounts of his death at Babylon in 323 BCE survive to the present day.

'In particular, none have provided an all-encompassing answer which gives a plausible and feasible explanation for a fact recorded by one source – Alexander's body failed to show any signs of decomposition for six days after his death,' said Dr Hall.

'The Ancient Greeks thought that this proved that Alexander was a god; this article is the first to provide a real-world answer.'

Dr Hall believes a diagnosis of GBS, contracted from a Campylobacter pylori infection (common at the time and a frequent cause for GBS), stands the test of scholarly rigour, from both Classical and medical perspectives.

Most arguments around Alexander's cause of death focus on his fever and abdominal pain.

However, Dr Hall says the description of him remaining of sound mind receives barely any attention.

She believes he contracted an acute motor axonal neuropathy variant of GBS which produced paralysis but without confusion or unconsciousness.

His passing was further complicated by the difficulties in diagnosing death in ancient times, which relied on presence of breath rather than pulse, she says.

These difficulties, along with the type of paralysis of his body (most commonly caused by GBS) and lowered oxygen demands, would reduce the visibility of his breathing.

A possible failure of his body's temperature autoregulation, and his pupils becoming fixed and dilated, also point to the preservation of his body not occurring because of a miracle, but because he was not dead yet.

'The elegance of the GBS diagnosis for the cause of his death is that it explains so many, otherwise diverse, elements, and renders them into a coherent whole.'

Last year it was claimed the fabled last will and testament of Alexander the Great may have finally been discovered more than 2,000 years after his death.

A London-based expert claims to have unearthed the Macedonian king's dying wishes in an ancient text that has been 'hiding in plain sight' for centuries.

The long-dismissed last will divulges Alexander's plans for the future of the Greek-Persian empire he ruled.

It also reveals his burial wishes and discloses the beneficiaries to his vast fortune and power.

Evidence for the lost will can be found in an ancient manuscript known as the 'Alexander Romance', a book of fables covering Alexander's mythical exploits.

Likely compiled during the century after Alexander's death, the fables contain invaluable historical fragments about Alexander's campaigns in the Persian Empire.

Historians have long believed that the last chapter of the Romance housed a political pamphlet that contained Alexander's will, but until now have dismissed it as a work of early fiction.

But a ten-year research project undertaken by Alexander expert David Grant suggests otherwise.

The comprehensive study concludes that the will was based upon the genuine article, though it was skewed for political effect.

The fabled last will and testament of Alexander the Great, illustrated above, may have finally been discovered. A London-based expert claims to have unearthed Alexander the Great's dying wishes in an ancient text (pictured) that has been 'hiding in plain sight' for centuries

WHO WAS ALEXANDER THE GREAT?

Alexander the Great is arguably one of history's most successful military commanders.

Undefeated in battle, he had carved out a vast empire stretching from Macedonia and Greece in Europe, to Persia, Egypt and even parts of northern India by the time of his death aged 32.

Only five barely intact accounts of his death at Babylon in 323 BCE survive to the present day.

None are from eyewitnesses and all conflict to varying degrees.

According to one account from the Roman era, Alexander died leaving his kingdom 'to the strongest' or 'most worthy' of his generals.

In another version, he died speechless in a coma, without making any plans for succession.

Alexander, born in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia, was the son of Philip II, king of Macedonia, and of Olympia, a princess of Epirus. Philip and Olympia wanted nothing less than the best for their son, so when he was 13, his parents hired Aristotle to be his personal tutor. Alexander was trained together with other children of the nobility at Aristotles Nyphaeon. It is here that Alexander met Hephastion, his future best friend and alter ego. Aristotle gave Alexander a thorough training in rhetoric and literature and stimulated his interest in science, medicine, and philosophy, all of which became of the utmost importance for Alexander in his later life. The two later became estranged, due to their difference of opinion on the status of foreigners; Aristotle saw them as barbarians, while Alexander sought to unite Macedonians and foreigners.

In 340 BC, when Philip went to Byzantium to fight rebels, Alexander, a mere 16 years old, was left in charge of Macedonia as regent, with the power to rule in Philip's name in his absence. That Alexander was given such a position at such a young age indicates that he was already accomplished in battle. But Alexander never got along well with his father, although Philip was proud of Alexander for the Bucephalus incident. Alexander had always been closer to Olympia than to Philip. Philip and Olympia also did not get along all that well, owing primarily to Olympia's non-Macedonian heritage.

The family essentially was split apart irreparably when Philip married a woman named Cleopatra, a Macedonian. At the wedding banquet, Cleopatra's father made a remark about Philip fathering a "legitimate" heir, i.e., one that was pure Macedonian. Alexander took exception and threw his cup at the man, and some sources say Alexander killed him. Enraged, Philip stood up and charged at Alexander, only to trip and fall on his face in his drunken stupor. Alexander, rather upset at the scene, is to have shouted:

"Here is the man who was making ready to cross from Europe to Asia, and who cannot even cross from one table to another without losing his balance."

When Philip divorced Olympia Alexander fled. Although allowed to return, he remained isolated untilPhilip was assassinated (some think that Olympia may have even had a role in Philip's murder), in the summer of 336 BC.

ALEXANDER ON THE MACEDONIAN THRONE

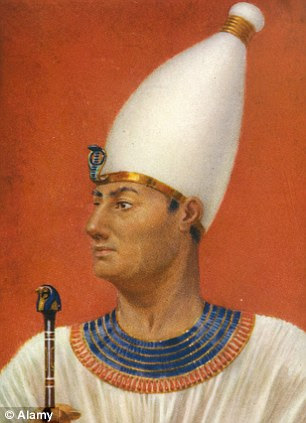

Alexander Rondanini

Glyptothek

Munich, Germany

THE CRASH OF THE GREEK RESISTANCE

Alexander ascended to the Macedonian throne when his father died. Once in power, he disposed quickly of all conspirators and domestic enemies by ordering their execution. Then he descended on Thessaly, where partisans of independence had gained ascendancy, and restored Macedonian rule. Before the end of the summer of 336 BC he had reestablished his position in Greece and was elected by a congress of states at Corinth.

But, Greek cities, like Athens and Thebes, which had pledged allegiance to Philip, were unsure if they wished to do the same for a twenty-year-old boy. Moreover, theHellenes considered Macedonian domination in the Greek states as an alien rule, imported from outside by the members of other tribes, the, as Plutarch says, allophyloi (Plutarchus, Vita Arati, 16). Likewise, northern barbarians that Philip had subdued were threatening to break away from Macedonia and wreak havoc in the north. Alexander's advisors suggested that he let Athens and Thebes go and to be gentle with the barbarians to prevent a revolt. However, in 335 BC, Alexander campaigned toward the Danube, to secure Macedonia's northern frontier. He carried out a successful campaign against the defecting Thracians, penetrating to the Danube River. Alexander marched quickly north and drove the rebelling barbarians beyond the Danube River and out of the way. On his return he crushed in a single week the threatening Illyrians.

On rumors of his death, a revolt broke out in Greece with the support of leading Athenians. Alexander marched south covering 240 miles in two weeks. Arrian related the story of how Alexander dealt with Thebes and Athens. There were rumors in these cities that Alexander had been killed, and that the time was right for them to separate themselves from Macedonia. Instead, in the fall of 335 BC, Alexander marched up to the gates of Thebes, and let them know that it was not too late for them to change their minds. The Thebans responded with a small contingent of soldiers, which Alexander repelled with archers and light infantrymen. The next day, Alexander's general, Perdiccas, attacked the gates. Perdiccas broke through and into the city, and Alexander moved the rest of his force in behind to prevent the Thebans from cutting Perdiccas off from the rest. The Macedonians then stormed the city, killing almost everyone in sight, women and children included. They plundered, sacked, burned and razed Thebes, as an example to the rest of Greece. Only the temples and the house of the poet Pindar were spared from distraction. Athens then quickly rethought its decision to abandon Alexander. Greece remained under Macedonian control.

Alexander's Empire at its height

Alexander began his war against Persia in the spring of 334 BC by crossing the Hellespont (modern Dardanelles) with an army of 35,000 Macedonians and 7,600 Greeks. He threw his spear from his ship to the coast and it stuck in the ground. He stepped onto the shore, pulled his weapon from the soil, and declared that the whole of Asia would be won by the spear. His chief officers, all Macedonians, included Antigonus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus.

The Macedonian army soon encountered the Persian army under King Darius III at the crossing of the river Granicus, near the ancient city of Troy. Alexander attacked an army of Persians and Greek hoplites (a heavily armed foot soldiers of ancient Greece) who distinguished themselves on the side of the Persians against the Macedonians. Alexander's forces defeated the enemy (totaling 40,000 men) and, according to tradition, lost only 110 men.

Then he turned northward to Gordion, home of the famous Gordian Knot. The legend behind the ancient knot was that the man who could untie it was destined to rule the entire world. Alexander simply slashed the knot with his sword and unraveled it.

Detail from the Alexander mosaic From the House of the Faun, Pompeii, c. 80 B.C.

National Archaeologic Museum, Naples, Italy

Continuing to advance southward, in November of 333 BC, Alexander met Darius in battle for the second time at a mountain pass at Issus, in northeastern Syria. The size of Darius's army is unknown but although the Persian army greatly outnumbered the Macedonians, the narrow field of battle allowed Alexander to defeat the Persians. The Battle of Issus ended in a great victory for Alexander. Cut off from his base, Darius fled northward, abandoning his mother, wife, and children to Alexander, who treated them with the respect due to royalty.

In the next year, he marched down the Phoenician coast and received the surrenders of all of the major cities there except for Tyre. A seven-month siege of the city followed, and the Tyrians eventually surrendered to Alexander. Then he continued south into Egypt after he had secured the entire Aegean coast.

ALEXANDER IN EGYPT

Alexander Rondanini

Glyptothek

Munich, Germany

Alexander entered Egypt in 331 BC. When he arrived, he was welcomed, and he ordered a city to be designed and founded in his name at the mouth of the river Nile. Alexandria would become one of the major cultural centers in the Mediterranean world in the following centuries.

In the spring of 331 Alexander made a pilgrimage to the great temple and oracle of Amon-Ra, Egyptian god of the sun, whom the Greeks identified with Zeus. The earlier Egyptian pharaohs were believed to be sons of Amon-Ra and Alexander, the new ruler of Egypt, wanted the god to acknowledge him as his son. The pilgrimage apparently was successful, and it may have confirmed in him a belief in his own divine origin.

While in Egypt, Alexander spontaneously decided to make the dangerous trip across the desert to visit the oracle at the temple of Zeus Ammon. On the way, he was blessed with abundant rain, and he was guided across the desert by ravens. At the temple, Alexander spoke to the oracle about matters that are unclear to most historians. Many sources, however, speculated that the priest told Alexander that he was the son of Zeus Ammon and that he was destined to rule the world.

He was then made pharaoh voluntarily by the Egyptians, who despised living under Persian rule. He exchanged letters with Darius while he was in Egypt, and the Persian offered a truce with Alexander with a gift of several western provinces of the Persian Empire, but Alexander refused to make peace unless he could have the whole empire. In the middle of 331 BC Alexander marched back to Persia to find Darius.

THE END OF THE PERSIAN EMPIRE

Alexander reorganized his forces at Tyre and started for Babylon with an army of 40,000 infantry and 7000 cavalry. He conquered the lands between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and found the Persian army which, according to the exaggerated accounts of antiquity, was said to number a million men at the plains of Gaugamela (near modern Irbil, Iraq). The Macedonians spotted the lights from Persian campfires one night, and they encouraged Alexander to lead his attack under cover of darkness. He refused to take advantage of their situation because he wanted to defeat Darius in an equally matched battle so that the Persian king would never again dare to raise an army against the Macedonians. The two armies met on the battlefield the next morning on October 1, 331 BC, and the Macedonian forces swept through the Persian army and slaughtered them. Darius fled as he had done at Issus to the mountain residence of Ecbatana, while Alexander occupied Babylon, the imperial capital Susa, and Persepolis. Henceforth, Alexander was proclaimed king of Persia, and to win the support of the Persian aristocracy he appointed mainly Persians as provincial governors. After four months, the Macedonians burned the royal palace to the ground thus completing the end of the ancient Persian Empire.

Yet a major uprising in Greece had Alexander so deeply worried, that after hearing that the rebellion had failed, he proclaimed the end of the Hellenic Crusade and discharged the all Greek forces.

Alexander continued his pursuit of Darius for hundreds of miles from Persepolis. When he finally caught up to him, he found the Persian king dead in his coach, assassinated by his own men. Alexander had the assassin executed and gave Darius a royal funeral.

MACEDONIAN NOBLES RESISTANCE AND THE MACEDONIAN LANGUAGE

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the Macedonians spoke their own native language, as the native language language of Alexander the Great was not understood by the ancient Greeks (Quintus Curtius Rufus, VI, 9, 37 ). Similarly, Plutarch points out that Alexander spoke to his fellow countrymen in Macedonian: "he [Alexander] called out aloud to his guards in the Macedonian language, which was a certain sign of some great disturbance in him" (Plutarch, Alexander, 51). Still, Alexander spoke also Greek, loved Homer, and respected his tutor Aristotle. At the same time though, there is much evidence that generally he was not fond of the Greeks of his day. The chronicler Curtius, describing the atmosphere before a battle, gave a notion of the different attitudes of the great commander, who psychognostically applied the principle of identity to every ethnic group in his army. In respect to the various motives for taking part in that war, Curtius wrote:

"Riding to the front line he [Alexander the Great] named the soldiers and they responded from spot to spot where they were lined up. The Macedonians, who had won so many battles in Europe and set off to invade Asia ... got encouragement from him - he reminded them of their permanent values. They were the world's liberators and one day they would pass the frontiers set by Hercules and Patter Liber. They would subdue all races on Earth. Bactrius and India would become Macedonian provinces. Getting closer to the Greeks, he reminded them that those were the people who provoked war with Greece, ... those were the people that burned their temples and cities ... As the Illirians and Trakians lived mainly from plunder, he told them to look at the enemy line glittering in gold ..."

Q. C. Rufus, Alexander III, 10, 4-10

After all, he thoroughly destroyed Thebes. Therefore, his empire is correctly called Macedonian, not Greek, for he won it with an army of 35,000 Macedonians and only 7,600 Greeks.

Alexander's increasingly Oriental behavior led to trouble with Macedonian nobles and some Greeks. In 330 BC a series of allegations was brought against some of Alexander's officers concerning a plot to murder him. Alexander tortured and executed his friend, Philotas (commander of the cavalry) the accused leader of the conspiracy, and several other high-ranking officials in order to eliminate the possibility of an attempt on his life. The question of the use of the ancient Macedonian language was raised by Alexander himself during the trial of Philotas. Alexander has said to Philotas:

"'The Macedonians are about to pass judgment upon you; I wish to know whether you will use their native tongue in addressing them.' Philotas replied: 'Besides the Macedonians there are many present who, I think, will more easily understand what I shall say if I use the same language which you have employed.' Than said the king: 'Do you not see how Philotas loathes even the language of his fatherland? For he alone disdains to learn it. But let him by all means speak in whatever way he desires, provided that you remember that he holds out customs in as much abhorrence as our language.'"

Quintus Curtius Rufus, Alexander, VI. ix. 34-36

The trial of Philotas took place in Asia before a multiethnic public, which has accepted Greek as their common language. Alexander spoke Macedonian with his conationals, but used Greek in addressing West Asians. Like Illirian and Tracian, ancient Macedonian was not recorded in writing. However, on the bases of about a hundred glosses, Macedonian words noted and explained by Greek writers, some place names from Macedonia, and a few names of individuals, most scholars believe that ancient Macedonian was a separate Indo-European language. Evidence from phonology indicates that the ancient Macedonian language was distinct from ancient Greek and closer to the Tracian and Illirian languages.

Another old-fashioned noble, Cleitus, was killed by Alexander himself in a drunken brawl. Heavy drinking was a cherished tradition at the Macedonian court when Alexander ran him through with a spear. Although he mourned his friend excessively and nearly committed suicide when he realized what he had done, all of Alexander's associates thereafter feared his paranoia and dangerous temper. Alexander next demanded that Europeans follow the Oriental etiquette of prostrating themselves before the king - which he knew was regarded as an act of worship by Greeks. But resistance by Macedonian officers and by the Greek Callisthenes (a nephew of Aristotle who had joined the expedition as the official historian of the crusade) defeated the attempt. The Greek Callisthenes was soon executed on a charge of conspiracy.

As the Macedonians marched into Parthia, the tone of the journey changed. Alexander had adopted the Persian style of dress, rather than his traditional Macedonian clothing, and his troops were unhappy with him. After all, up until that point, the Macedonian soldiers respected him immensly, as they saw him as a partner working for the common good of all Macedonians, the nobles and the masses. He was well known for calling on his fellow countrymen to join him in battle by their own will:

"However he told them he would keep none of them with him against their will, they might go if they pleased; he should merely enter his protest, that when on his way to make the Macedonians the masters of the world, he was left alone with a few friends and volunteers. This is almost word for word as he wrote in a letter to Antipater, where he adds, that when he had thus spoken to them, they all cried out, they would go along with him whithersoever it was his pleasure to lead them."

ALEXANDER IN INDIA

Marble head of Alexander

Acropolis Museum

Athens, Greece

In the spring of 327 BC, Alexander and his army marched into India invading Punjab as far as the river Hyphasis (modern Beas). At this point the Macedonians rebelled and refused to go farther.

The greatest of Alexander's battles in India was against Porus, one of the most powerful Indian leaders, at the river Hydaspes. On July 326 BC, Alexander's army crossed the heavily defended river in dramatic fashion during a violent thunderstorm to meet Porus' forces. The Indians were defeated in a fierce battle, even though they fought with elephants, which the Macedonians had never before seen. Alexander captured Porus and, like the other local rulers he had defeated, allowed him to continue to govern his territory. Alexander even subdued an independent province and granted it to Porus as a gift.

In this battle Alexander's horse, Bucephalus, was wounded and died. Alexander had ridden Bucephalus into every one of his battles in Greece and Asia, so when it died, he was grief-stricken and founded a city in his horse's name.

Alexander's next goal was to reach the to travel south down the rivers Hydaspes and Indus so that they might reach the Ocean on the southern edge of the world. The army rode down the rivers on the rivers on rafts and stopped to attack and subdue villages along the way. During this trip, Alexander sought out the Indian philosophers, the Brahmins, who were famous for their wisdom, and debated them on philosophical issues. He became legendary for centuries in India for being both a wise philosopher and a fearless conqueror.

One of the villages in which the army stopped belonged to the Malli, who were said to be one of the most warlike of the Indian tribes. Alexander was wounded several times in this attack, most seriously when an arrow pierced his breastplate and his ribcage. The Macedonian officers rescued him in a narrow escape from the village. Alexander and his army reached the mouth of the Indus in July 325 BC and turned westward for home.

ALEXANDER'S MARIAGE

In the spring of 324, Alexander held a great victory celebration at Susa. He and 80 close associates married Iranian noblewomen. In addition, he legitimized previous so-called marriages between soldiers and native women and gave them rich wedding gifts, no doubt to encourage such unions. When he discharged the disabled Macedonian veterans a little later, after defeating a mutiny by the estranged and exasperated Macedonian army, they had to leave their wives and children with him. Because national prejudices had prevented the unification of his empire, his aim was apparently to prepare a long-term solution (he was only 32) by breeding a new body of high nobles of mixed blood and also creating the core of a royal army attached only to himself. After his death, nearly all the noble Susa marriages were dissolved. He established training programs to teach Persians about Greek and Macedonian culture, and he married Roxane, a Persian.

ALEXANDER'S DEATH

We will probably never know the truth, of Alexander's mysterious death, even though new theories are still coming out. Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king and the great conqueror, died at the age of 33, on June 10, 323 BC. Three days earlier, on the 7th of June, 323 BC, the Macedonians were allowed to file past their leader for the last time before he finally succumbed to the illness. Alexander died without designating a successor. His death opened the anarchic age of the Diadochi and the Macedonian Empire will eventually cease to exist.

From Alexander The Great's campaign which stretched from Greece to northern India, to Atilla The Hun's rule of territories from Germany to the Caspian Sea,

[Marble statue from Gabii Louvre, Paris, France.

From the most brutal beginnings Genghis Khan (left) survived to unite the Mongolian tribes and conquer territories including Afghanistan. Alexander The Great (right) had conquered Greece by the age of 22

1. GENGHIS KHAN

1162-1227

Originally known as Temüjin of the Borjigin, Genghis was born holding a clot of blood in his hand. His father was khan of a small tribe, but he was murdered when Temüjin was still very young. The new tribal leader wanted nothing to do with Temüjin's family, so with his mother and five other children, Temüjin was cast out and left to die. Of all those in this list, he is the only one to start with nothing. From the most brutal beginning possible, Genghis survived to unite the Mongolian tribes and conquer territories as far apart as Afghanistan and northern China. He left a mountain of skulls that remained for years in China. Genghis Khan paved the way for his grandson Kublai to become emperor of a united China and founder of the Yuan dynasty. In all, Genghis conquered almost four times the lands of Alexander the Great. He is still revered in Mongolia and in parts of China.

2. ALEXANDER THE GREAT

356-323 BC

At different times, Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar and Caligula all visited Alexander's glass tomb in Alexandria, Egypt. Augustus kissed the ancient corpse and accidentally broke the nose; Caligula stole Alexander's breastplate... Alexander was born a prince of Macedonia and tutored by Aristotle. By the age of 22, he had conquered Greece and set sail to Asia Minor. Here, in what is now central Turkey, he cut in half the famous Gordian Knot, fulfilling a Greek legend that whoever unravelled it would rule the world. In Syria, he destroyed the armies of Darius III and gained control of the entire Eastern Mediterranean coast. He entered Egypt as a liberator. From there, he fought in India, where his legendary horse Bucephalus was killed. He was still on campaign at the age of 33 when a fever destroyed his health. At the time his empire stretched from Greece to northern India.

Despite being illiterate, Tamerlane was highly intelligent. He spoke at least three languages and invented a variant of chess. He conquered Persia, Armenia, Georgia and part of Russia

3. TAMERLANE

1336-1405

'Timur the Lame' was born in modern day Uzbekistan, about 400 miles north of the city of Kabul. He had a slight paralysis down one side as a child, which meant his early career was in politics. Despite being illiterate, he was highly intelligent. He spoke at least three languages and invented a variant of chess. He rose quickly to become senior minister to the Mongol khan, then Tamerlane overthrew the khan and began a reign of warfare, slaughter and, yes, mountains of skulls. Tamerlane revered Genghis and claimed to be descended from his second son. He used the city of Samarkand as his base, which Genghis himself had conquered. From there, Tamerlane conquered Persia, Armenia, Georgia and part of Russia.

Atilla The Hun ruled territories from Germany to the Caspian Sea for almost 20 years

4. ATILLA THE HUN

406-453

The man known as 'The Scourge of God' inherited his throne in modern day Hungary in AD 434. He began his rule by slaughtering Goth tribes in modernday Germany and Austria, then attacked the enfeebled Roman empire. At one point Atilla offered to marry the Western Emperor's sister, but made it clear that the dowry would be half her brother's lands. This splendid offer was refused. 'The whole breadth of Europe... was at once invaded, and occupied and desolated, by the myriads of barbarians whom Atilla led into the field,' wrote Edward Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Atilla ruled territories from Germany to the Caspian Sea for almost 20 years. On his wedding night, he drank heavily and passed out. Whether it was a nosebleed or a rupture, Atilla choked to death on his own blood.

Charlemagne defended a Christian Europe from Muslim Saracens and pagan Saxons, often beheading thousands in a single day

5. CHARLEMAGNE

742-814

Charles the Great, King of the Franks, ruled a European empire based mainly around France, Germany and parts of Italy. Although he could not write, he spoke Teutonic, Latin and Greek. He was 6ft 4in, a monstrous height for the period, which has since been confirmed by measurement of his skeleton. Oddly, his father was known as Pepin the Short and was around 5ft tall. Charlemagne's first campaign came at the age of 27, when the Pope sought his aid in repelling the Lombards of Italy. Charlemagne smashed them in the field and took the crown of Lombardy as his own. From his capital of Aachen in modern-day Germany, he went on to fight 53 campaigns, most of which he led himself. He defended a Christian Europe from Muslim Saracens and pagan Saxons, often beheading thousands in a single day. He died aged 72 from a fever.

Thutmose III never lost a battle in 18 summer campaigns (right). By the time of his death, Ashoka The Great (left) ruled India, Pakistan, Nepal and Afghanistan

6. PHARAOH THUTMOSE III OF EGYPT

1479-1425 BC

Responsible for the obelisk known as Cleopatra's Needle on the bank of the Thames, Thutmose III never lost a battle in 18 summer campaigns. He was one of the first rulers to understand supply lines and sea power. Having inherited the throne of Egypt aged seven, he spent the first two decades as co-regent with his father's wife. When she died, he conquered lands in Palestine, Syria, Nubia and Mesopotamia.

It was Thutmose III who established Egypt as a major power in the eastern Mediterranean and his reign was a golden era of temple building and great riches (and he was humane in his treatment of the vanquished). He died aged 61.

7. ASHOKA THE GREAT

304-232 BC

Born to the Mauryan (ancient Indian) imperial house, Ashoka loved to hunt and was a warlike young man, the favourite of his father. When his father died, Ashoka killed all his brothers and went on a brutal rampage to expand the empire. It culminated in the slaughter by the Daya river, where more than 100,000 citizens were killed by his army. Afterwards Ashoka was appalled at the carnage and vowed then to embrace Buddhism. He was a changed man. The laws that followed were relatively just and he set up pillars with his edicts carved on them across India. He even promoted vegetarianism and treated all his subjects as equals regardless of caste. By the time of his death, he ruled India, Pakistan, Nepal and Afghanistan.

Cyrus The Great became the first emperor of Persia, uniting the tribal Medes and Persians

8. CYRUS THE GREAT

580-529 BC

Of a minor royal family, Cyrus became the first emperor of Persia, uniting the tribal Medes and Persians. As well as the usual mountains of skulls, he created what may be the first charter of human rights, available to be seen at the British Museum. He freed the Jews in Babylon when he conquered that city. Despite his benevolent side, Cyrus spent years conquering lands, murdering his enemies and establishing a vast empire that stretched from India to Greece.

Ch'in Shih Huang (left) inherited a minor throne in China at the age of 15. Under the rule of Augustus Caesar (right), the Roman empire expanded into Hungary, Croatia and Egypt as well as securing Spain and Gaul

9. CH'IN SHIH HUANG

259-210 BC

The boy known as Ch'eng inherited a minor throne in China at the age of just 13. As an adult, he was a superb organiser. His achievement was not just in conquering the different regions of China in just nine years, but unifying them as an empire. With two trusted ministers, he established a bureaucracy, taxation, standardised weights and measures and a system of ruthless punishments for lawbreaking. The first emperor of China is perhaps most famous for the terracotta army guarding his tomb. More than 8,000 life-sized warriors were created, as well as 600 horses and 130 chariots. In the centralised government he created, the emperor was almost a figurehead. The structure of government was so successful that when Shih Huang died at 49, his two most powerful ministers carried on without him for four years before they quarrelled and his death became public knowledge.

10. AUGUSTUS CAESAR

63 BC-14 AD

Born Octavian, the great-nephew of Julius Caesar was technically the first Roman emperor. He was made Consul after Caesar's death, then formed a triumvirate with Mark Anthony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. They secured their power in Rome by executing thousands. The title Augustus, meaning 'exalted', was granted by the senate. Octavian changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar to honour his predecessor, creating a tradition that would last 2,000 years - to the German Kaisers and Russian Czars. Augustus was not a battle king. However, under his rule, the Roman empire expanded into Hungary, Croatia and Egypt as well as securing Spain and Gaul. He added more land than Julius Caesar and was worshipped as a god in Rome.

Alexander the Great Refuses to Take Water , 1792 Cades, Giuseppe

Full View of the Alexander Sarcophagus

Alexander-de-Grote. 16c. Museum Boijmans. Neth.

Alexander de Grote. Gerard de Jode engr. 16c. Museum Boijmans Neth.

;

Alexander on his deathbed surrounded by mourners

Greek archaeologists have come one step closer to solving the mystery of who is buried in a vast ancient tomb dating to Alexander the Great's era.

Skeletal remains have been found in and around a stone-lined cistern in the opulent 4th Century B.C. burial site in Amphipolis, north-east Greece.

The site is believed to be the largest ancient tomb to have been discovered in Greece, and has spurred speculation as to whether Alexander the Great or a member of his family was buried there.

Solving a mystery: Archaeologists have found skeletal remains inside a grave in the innermost chamber of an ancient tomb in Amphipolis, north Greece. There has been great speculation in recent months whom the opulent burial belongs to

Alexander died in Babylonia, present day Iraq, but his burial site is not known, and Greece's culture ministry said today the opulence of the tomb indicates that a 'distinguished public figure' is buried there.

The skeletal remains are being examined for identification, Greece's culture ministry said in a statement.

The body had been placed in a wooden coffin, which disintegrated over time. The skeletal remains were found both inside and outside the rectangular stone-lined cist, under the floor of the cavernous, vaulted structure that is 26 feet (eight metres) tall

Iron and bronze nails as well as carved bone and glass decorations from the coffin were also found scattered in the grave.

Findings: Greece's Culture Ministry said skeleton was strewn in and around the stone-lined cistern, pictured, under the floor of the cavernous, vaulted structure that is 26ft tall.Opulent: There has been speculation that the tomb could be that of Alexander the Great

New find: surviving fragments of carved bone and glass coffin ornaments found in the tomb at Amphipolis

The great Amphipolis Tomb seen for the first time on video

WHO WAS ALEXANDER THE GREAT?

Alexander III of Macedon was born in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia in July 356 BC.

He died of a fever in Babylon in June 323 BC.

Alexander led an army across the Persian territories of Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt claiming the land as he went.

His greatest victory was at the Battle of Gaugamela, now northern Iraq, in 331 BC, and during his trek across these Persian territories, he was said to never have suffered a defeat.

This led him to be known as Alexander the Great.

Following this battle in Gaugamela, Alexander led his army a further 11,000 miles (17,700km), founded over 70 cities and created an empire that stretched across three continents.

This covered from Greece in the west, to Egypt in the south, Danube in the north, and Indian Punjab to the East.

Alexander was buried in Egypt.

His fellow royals were traditionally interred in a cemetery near Vergina, far to the west.

The lavishly-furnished tomb of Alexander's father, Philip II, was discovered during the 1970s.

Archaeologists in the past have said the grave likely belonged to a prominent Macedonian and some have hoped it might have been built for Alexander the Great's mother or wife, while others think it belongs to a military man.

A statement from the Culture Ministry said: 'It is probably the monument of a dead person who became a hero, meaning a mortal who was worshipped by society at that time.

'The deceased was a prominent person, since only this could explain the construction of this unique burial complex.'

‘It is an extremely expensive construction, whose cost, clearly, is unlikely to have been borne by a private citizen.'

Michalis Tiverios, a professor of archaeology at the University of Thessaloniki who has not been involved with the dig, said the human remains should provide valuable information on the occupant of the tomb, which at about 49 ft (15 metres) long and 15 ft (4.5 metres) wide is one of the biggest ever found in the country.

‘It's a very important find because it will help us learn the sex of the person buried there, and possibly their approximate age,’ he said.

Professor Tiverios believes one possible candidate would be Nearchos, one of Alexander's closest aides who led his fleet back from India to modern Iraq, and who grew up in Amphipolis.

The ministry confirmed fears that the tomb had been thoroughly and repeatedly plundered during antiquity.

‘Whatever objects of value the first thieves missed was taken by others later,’ Professor Tiverios said.

Excavations at the site in northeastern Greece near the city of Thessaloniki began in 2012. They captured global attention in August when archaeologists announced the discovery of vast tomb guarded by two sphinxes and circled by a 497-metre marble wall.

Since then the tomb has also yielded a mosaic made of coloured pebbles depicting the abduction of Persephone, the daughter of Zeus, as well as two sculpted female figures also known as Caryatids.

The tomb dates to 300-325 B.C. Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C. after a military campaign through the Middle East, Asia and northeast Asia.

Experts believe the ancient mound, situated around 65 miles (100km) from Thessaloniki (shown on the map) was built for a prominent Macedonian in around 300 to 325 BC

Clockwise from top right shows two headless, marble sphinxes found above the entrance to the barrel-vaulted tomb, details of the facade and the lower courses of the blocking wall, the antechamber's mosaic floor, a 4.2-metre long stone slab, and the upper uncovered sections of two female figures. The second and third chambers, not pictured, have not yet been explored

Headcase: One of the shows the broken-off head's from one of the large marble sphinxes that decorate the entrance to the tomb

A large, damaged mosaic floor of the ancient Greek god of the underworld, Pluto, abducting the goddess Persephone on a horse-drawn chariot as the god Hermes looks on, found in the tomb

C.W. Eckersberg, Danish, 1783 - 1853 Alexander the Great on his sickbed. 1806

Scene inspired by the Battles of Alexander the Great" - Attributed to Panayiotis Douxaras (1662-1729)

Scene inspired by the Battles of Alexander the Great" - Attributed to Panayiotis Douxaras (1662-1729)

Alexander the GreatNy Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

The long-dismissed last will and testament divulges Alexander's (pictured) plans for the future of the Greek-Persian empire he ruled

No comments:

Post a Comment