HOW THE US NAVY CAN PREPARE FOR AN ARCTIC WAR AGAINST RUSSIA AND CHINA: USE AND MODERNIZED OLD CARRIERS AND DREADNOUGHTS AS MULTIROLE ICEBREAKERS/ ARSENAL SHIPS OR AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT SHIPS

PREPARING THE US NAVY IN THE ARCTIC

A U.S. SECURITY STRATEGY FOR THE ARCTIC

In March 2021, three Russian submarines simultaneously broke through the ice near the North Pole. Each boat could carry 16 ballistic missiles, and each missile could field multiple nuclear warheads. The submarines were soon joined by two MiG-31 aircraft and ground troops participating in Umka-2021, a Russian military exercise.

The exercise in March highlighted increased Russian military activity in the Arctic, but that was not the sole Russian signal. U.S. Alaska Command, under U.S. Northern Command, reported that they had intercepted more Russian military aircraft near the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone in 2020 than at any other time since the end of the Cold War. In April, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that Russia is trying “to exert control over new spaces. It is modernizing its bases in the Arctic and building new ones.” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov responded by saying, “We hear whining about Russia expanding its military activities in the Arctic. But everyone knows that it’s our territory, our land.”

SLAP AN ICEBREAKER HULL UNDERNEATH THE OLD DREADNAUGHTS OR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS

Russia is not the only authoritarian power with increased interest in Arctic affairs. In January 2018, Chinese officials published their first Arctic strategy document and attempted to buy and greatly expand Finland’s Kemijärvi air base for use by large Chinese aircraft, ostensibly for Arctic research. Their offer was rejected, supposedly because the northern airfield is next to Finland’s Rovajärvi artillery range. This fits a pattern. China has built Arctic research stations, conducted ongoing oceanographic surveys, and attempted infrastructure development across the region, projects that some believe have geostrategic or military purposes.

In order to better position the United States for geopolitical competition in the region, the Biden administration should write and publish a new national security strategy for the Arctic. The United States has a moribund 2013 Arctic strategy that was superseded by events and ignored by the Trump administration. In 2019, the Office of the Secretary of Defense released an Arctic strategy, and the Air Force, Navy and Army each released their own subordinate strategies. However, these individual strategies were not coordinated before being released, did not fully integrate efforts with civilian foreign policy agencies, and in some cases were produced only because of pressure from Sen. Dan Sullivan from Alaska.

It is time to rectify those omissions. A new Arctic security strategy should focus on deterring Russian and Chinese military attacks and preventing their attempts to weaken the established Arctic international order. To avoid mistakes from past Arctic national security, the Biden administration should build an Arctic strategy that responds to future security threats, can be resourced within constrained national budgets, and that integrates military and civilian actions across the government and private sector.

Goals for an Arctic Strategy

Though the Biden administration has yet to release a National Defense Strategy and National Military Strategy, guideposts exist to begin conceptualizing a new Arctic security strategy. Blinken expressed the U.S. desire to keep the Arctic peaceful when speaking at the May 2021 Arctic Council ministerial meeting. The administration’s March 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance focuses on deterring and preventing adversaries from threatening the United States and its allies, inhibiting access to the global commons, or dominating key regions (i.e., the Indo-Pacific, Europe, and the Western Hemisphere). Even though the document does not mention the region, its priority actions are applicable to the Arctic, such as leading a stable and open international system underwritten by alliances, partnerships, multilateralism, and international rules.

Any new U.S. Arctic security strategy should have three goals: deter military attacks against U.S. or allied territory originating from the Arctic, prevent China or Russia from weakening existing rules-based Arctic governance through coercion, and prevent regional hegemony by either China or Russia. To accomplish these goals, U.S. strategy should develop military capabilities for use in the North American and European Arctic subregions and then demonstrate the ability to use them in harsh Arctic conditions. The U.S. government should persuade regional allies and partners that the United States can be a trusted security partner in the region. Finally, the strategy should contain inducements to the private sector to build dual-use Arctic infrastructure that benefits the private sector while giving the military platforms from which to observe and operate in the Arctic.

The Arctic’s Geopolitical Context

Any Arctic strategy is constrained by the region’s harsh terrain and weather conditions. High latitudes and harsh weather make communications, global positioning, and domain awareness a significant challenge across the Arctic. In the Alaskan Arctic, ground-based infrastructure outside the Anchorage-Fairbanks-Prudhoe corridor is localized rather than interconnected and is dependent on bulk summer resupply. U.S. security infrastructure in the Arctic comprises aging early warning radars in Alaska and Greenland, missile defenses and significant 5th-generation fighter aircraft in Alaska, submarines in Arctic waters, and modest rotational forces in Iceland and Norway. U.S. relations with Arctic nations have been generally cooperative, with the exception of relations with Russia on non-Arctic issues since 2014. Finally, different security issues are associated with the three Arctic subregions — the North American, European, and Russian Arctic — with the European Arctic subregion being the area with the greatest security challenges.

A new Arctic strategy should factor in climate change, protect the Arctic Council’s viability, and assume a future budget-constrained environment. It’s safe to assume that Arctic warming will continue and regional activity — shipping, mining, commercial fishing, tourism, etc. — will increase as a result. Transnational cooperation on Arctic science and soft-security issues (search and rescue, oil spill prevention, etc.) is a valued behavior. As a result, maintaining the Arctic Council as a viable international forum serves the continued interests of Arctic states both because of the substantive work done by the council’s working groups and as a venue for transarctic consultations. A new strategy should not needlessly threaten this progress.

Finally, the next U.S. Arctic strategy will be means-constrained. The Arctic will be a relatively low budget priority for the U.S. government and its military services. None of the recent U.S. military strategies for the Arctic obligate significant spending in the region for new capabilities or permanent presence.

Below I list the main goals and new or promised capabilities of recent U.S. defense strategies for the Arctic. With the exception of the Air Force’s strategy, none of the strategies commit the United States to major defense investments in the Arctic, and the Air Force expenditures are not aimed at the Arctic per se, but are instead global capabilities that happen to be based in the Arctic or in space. Indeed, the gaps identified below are big-ticket items. The assumption, then, is that any new Arctic security strategy will be means-constrained going forward but should compensate for the gaps identified in the table.

U.S. Arctic military strategies (2019 to 2021)

Goals and Priorities Arctic Capabilities

An arsenal ship is a concept for a floating missile platform intended to have as many as five hundred vertical launch bays for mid-sized missiles, most likely cruise missiles. In current U.S. naval thinking, such a ship would initially be controlled remotely by an Aegis Cruiser, although plans include control by AEW&C aircraft such as the E-2 Hawkeye and E-3 Sentry. Originally proposed by VADM Joseph Metcalf, DCNO Surface Warfare, as a component of the "Surface Combatants of the 21st Century" initiative in the mid-1980's. Later, proposed by the U.S. Navy in 1996, the arsenal ship had funding problems, with the United States Congress canceling some funding, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) providing some funding to individual contractors for prototypes. Some concept artwork of the Arsenal Ship was produced, with some images bearing the number "72", possibly hinting at an intent to classify the arsenal ships as a battleship, since the last battleship ordered (but never built) was USS Louisiana (BB-71). The arsenal ship would have a small crew and as many as 500 vertical launch tubes for missiles to provide ship-to-shore bombardment for invading troops. The Navy calculated a $450 million price for the arsenal ship, but Congress scrapped funding for the project in 1998. The U.S. Navy has since modified the four oldest Ohio-class Trident submarines to SSGN configuration, allowing them to carry up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles using vertical launching systems installed in the tubes which previously held strategic ballistic missiles, creating a vessel roughly equivalent to the arsenal ship concept. In 2013, Huntington Ingalls Industries revived the idea when it proposed a Flight II version of the LPD-17 hull with a variant carrying up to 288 VLS cells for the ballistic missile defense and precision strike missions. China has conducted studies and tested models of partially and completely submersible arsenal ship concepts.

South Korea is also planning to deploy three arsenal ships by the late 2020s.

Office of the Secretary of Defense

Arctic Strategy (2019)Defend the homeland and U.S. sovereignty in the Arctic

Maintain a credible deterrent in the Arctic

Shape the Arctic’s geopolitical landscape

Respond effectively to regional contingencies

Maintain flexibility for U.S. power projection

Ensure freedom of navigation and overflight

Limit the ability of China and Russia to engage in malign or coercive behavior

Intent: “The U.S. will require an agile, capable and expeditionary force with the ability to project power into and operate within the [Arctic] region.”

New capabilities: Funding for one Polar Security Cutter; reactivation of Navy’s 2nd Fleet headquarters; and stationing two F-35 squadrons at Eielson air base in Alaska.

Gaps: Dedicated funding for Arctic military capabilities.

Air Force Arctic Strategy (July 2020)

• Vigilance via warning and defense capabilities

• Power projection from Alaska and Greenland

• Cooperation with allies and partners

• Preparation via exercises, training, and research and development

Intent: Expand Air Force Arctic capabilities.

New capabilities: Missile warning and defense; satellite communications and data links (Starlink); expanded weather forecasting; adoption of expeditionary, modular infrastructure.

Gaps: Cruise missile early warning system, unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems.

Navy Strategic Blueprint (January 2021) Defend the homeland

Deter aggression and discourage malign behavior

Ensure strategic access and freedom of the seas

Strengthen existing and emerging alliances

Intent: Maintain enhanced presence and partnerships and build a more capable Arctic naval force.

New capabilities: The Navy will “find new ways to integrate and apply naval power with existing forces,” and “invest in key capabilities that enable naval forces to maintain enhanced presence and partnerships;” development of unmanned underwater vehicles and buoys for mobile sensing; Keflavik airfield expansion.

Gaps: Acquisition of “key capabilities,” ice-hardened surface vessels, Navy icebreaking capabilities, Arctic port(s).

Army Regaining Arctic Dominance (January 2021)Homeland defense of Alaska

Defense support to civilian authorities

Support for search and rescue operations

International partnerships

Intent: Ensure land dominance in the Arctic; “Generate Arctic-capable forces ready to compete and win in extended operations in extreme cold weather and high-altitude environments.”

New capabilities: Creation of an Arctic Multi-Domain Task Force; recasting two Alaska-based brigade combat teams to operate for extended periods in the Arctic winter; increased winter training; development of a new Arctic small-unit support vehicle.

Gaps: Logistical and infrastructure capabilities for sustained Arctic operations.

Arctic Threats and Opportunities

The key threats to U.S. interests in the region are from Russian military forces in the Arctic and from Chinese influence attempts. Russian military activity in the Barents and Greenland Seas (the northern part of the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap) poses the most direct threat to U.S. security interests. Russian forces there could attack the U.S. homeland, ships and data links crossing the North Atlantic, and threaten NATO allies in northern Europe. Russian forces in the Bering and Chukchi Seas off the Alaskan coast are equally concerning. Russian capabilities could also be used to flout international law through unilateral assertions of control along the Northern Sea Route or the undersea Lomonosov Ridge, should the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf rule against Russia’s recent expansive claims to the Arctic seabed.

China’s regional actions are troubling, particularly its use of government-linked investments, loans, and trade deals to influence Arctic states or populations. Threats could also arise from the military potential in China’s bathymetric mapping or its polar research stations across Scandinavia. Any U.S. security strategy in the Arctic should alleviate these threats.

The most obvious opportunities for the United States in the Arctic are in private-sector infrastructure development and security coordination with allies. Poor infrastructure and communications plague Alaska. A hard-security strategy that prioritized infrastructure development in the name of national security, a green-energy transformation, or broadband connectivity initiatives could improve infrastructure and resilience in Alaska. Internationally, security coordination among U.S. allies and partners could generate momentum on nonsecurity behavioral norms for resource extraction, investments, and economic cooperation across the Arctic.

The Strategy’s Ways and Means

To deter Russia and China from threatening U.S. interests in the Arctic, the U.S. military needs to demonstrate presence in the region beyond submarines. Submarines can deter large-scale attacks but are less useful against coercion and intimidation. Deterring Russia will require Navy surface assets (manned and unmanned) and a more robust air and ground presence in the European and North Atlantic Arctic. It is difficult to police fisheries, monitor potentially hostile surface ships, or target airborne intruders without capabilities in the region. As Adm. James Foggo said of the Arctic when commanding Allied Joint Forces Command in Italy, “In order to deter, you have to be present. You’ve got to be there and you’ve got to be there quickly.” Gen. Glen VanHerck, commander of U.S. Northern Command and the North American Aerospace Defense Command, made similar remarks in late April 2021.

Capabilities

Budget constraints, however, will prevent large-scale acquisition of military equipment designed for the Arctic. There are just too many competing demands on the defense budget. A handful of modern icebreakers and limited numbers of the Army’s new cold-weather vehicle may be the extent of new, manned Arctic capabilities funded for the foreseeable future. That said, the United States could shift cold-weather-capable equipment to the region, especially unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms. Unmanned capabilities need not have been developed for the Arctic per se but could be adapted for use in the region.

There is a role for the U.S. private sector in developing Arctic capabilities and infrastructure if given the right government inducements. One promising area is satellite communication and positioning systems. Satellite companies are potentially attractive government partners. The U.S. military is looking into private-sector efforts such as the OneWeb and Starlink polar communication satellites. The European Space Agency is doing the same with Arctic weather satellites. There is no reason these initiatives could not be expanded.

The Biden administration’s Arctic strategy should consider the role of extractive industries (oil, mining, timber, fishing) in the region. Those industries have built much of the nonmilitary infrastructure in Alaska. In the future, as the global economy shifts from hydrocarbons to green energy, government efforts to foster infrastructure development could focus on distributed electricity grids, port facilities, and overland freight transport associated with mineral extraction (particularly rare earth minerals) rather than on oil and gas. All are consistent with the Biden climate plan. New ports and rail lines could be funded through cost-sharing agreements between the government and business, which could make infrastructure cost-effective for business while saving the taxpayer money. The private sector could use the infrastructure during normal times, with the U.S. military having priority use during military exercises or national emergencies.

Political Will

Demonstrating the political will to use Arctic capabilities unilaterally or in conjuncture with allies and partners is the other prerequisite for successful deterrence and defense. The most important priority should be to convince allies that the United States is a reliable security partner. Some of that persuasion has already begun with the Biden administration’s reaffirmation of the U.S. commitment to NATO’s Article 5 security guarantees and Blinken’s consultations in Denmark before the May 2021 Arctic Council ministerial meeting.

DESIGN THIS ASSAULT SHIP WITH THE LIKES OF AN ICEBREAKER/ARSENAL SHIP AND WITH NUCLEAR PROPULSION. TWO ATTACK GROUPS CAN VERY WELL COVER THE ARCTIC AND MORE THAN NEUTRALIZE THE RUSSIAN BASES IN THE AREA.

Persuading allies also requires demonstrating the ability to come to their defense if needed, regardless of climate conditions. Unilateral, bilateral, and “mini-multilateral” military exercises are all useful as practice and as international signals in the Arctic. Unilaterally, the U.S. Army is starting to relearn how to operate in the Arctic, as highlighted in its Arctic strategy. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps learned important lessons from NATO’s Trident Juncture exercise in 2018 and smaller exercises since then. More exercises are needed to demonstrate to friend and foe alike that the U.S. military can again operate in cold climates.

In addition, the United States should expand its use of flexible basing and deployment agreements with allies. The recent agreement covering the U.S. military’s use of the Ramsund naval facility and Evenes air base in northern Norway are a good start. A similar arrangement could be made for the Danish air force to have permanent facilities at the U.S. base in Thule, Greenland, for search and rescue, air surveillance, anti-submarine warfare, and air interdiction missions, something that could tie allied forces more closely together, better defend this early warning facility, and improve surveillance in the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap. Expansion of the runway and facilities on Norway’s Jan Mayen island and refurbishing an additional airfield in Greenland in conjunction with the Danes could serve similar purposes. Finally, the United States could coordinate existing niche capabilities amongst Arctic allies, an Arctic version of NATO’s Connected Forces Initiative.

The Way Forward

The Biden administration should publish a new Arctic national security strategy. The last U.S. Arctic strategy was written in 2013, before the country refocused on geopolitical competition with Russia and China. The strategy should prioritize deterring attacks from the Arctic on U.S. or allied territory, minimizing and defending against Russian or Chinese coercion, and preventing either country from achieving future regional hegemony. The United States could achieve these objectives through cost-effective military acquisition, incentives for private-sector infrastructure development, activities that demonstrate military presence, and political and military commitments to Arctic allies.

The Biden administration has a lot on its plate, and has yet to produce a final National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, or National Military Strategy. Nevertheless, the government should begin crafting an updated national strategy for the Arctic. The region is important for U.S. national security, and is increasingly a theater for competition with Russia and China.

MODIFY THE DREADNOUGHTS AS ICEBREAKERS

- Arctic Ocean Icebreaker

- Amphibious assault ship

- Nuclear Aircraft Carrier, CVN

- Missiles platform

- Forward Force Projection Ship

From this battleship to a Multi Role Combatant ship

The addition of a 16 inch thick protective armor on all the surface of the ship ie. Flight deck, bridge, sides etc.

HMS Daring, a new £1 billion warship: Using the new material, future ships could look radically different - and be able to survive multiple hits without sinking

The secret of this syntactic foam starts with a matrix made of a magnesium alloy, which is then turned into foam by adding strong, lightweight silicon carbide hollow spheres developed and manufactured by DST.

A single sphere's shell can withstand pressure of over 25,000 pounds per square inch (PSI) before it ruptures—one hundred times the maximum pressure in a fire hose.

The hollow particles also offer impact protection to the syntactic foam because each shell acts like an energy absorber during its fracture.

The composite can be customized for density and other properties by adding more or fewer shells into the metal matrix to fit the requirements of the application.

This concept can also be used with other magnesium alloys that are non-flammable.

The new composite has potential applications in boat flooring, automobile parts, and buoyancy modules as well as vehicle armor.

Add 400 feet at the stern, to provide an elevator to a hangar below deck and below the hangar install an LSD type attack amphibious assault module, thus creating a multi role ship.

LPDs can be used as a landing ship, helicopter platform and well deck. This system would give LPD-28 air defenses and the ability to hit inland and other enemy ships in the water. The ship could also provide fire support for vehicles that cannot reach certain areas - such as AH-1 attack helicopters. Pictured is an LPD-19

Lockheed Martin wants to outfit LPD-28 with the Aegis Combat System, giving it the ability to defend itself as well as pick up vehicles. Pictured is the LPD-26

Currently, the 'Baseline 9' Aegis equipped ships are the only vessels capable of defending against these threats.

This new system would also give LPD-28 air defenses and the ability to hit inland and other enemy ships in the water.

The ship could also provide fire support for vehicles that cannot reach certain areas.

Lockheed sees this as a 'Navy in a box' or a self-contained fight unit that could reach even the most dangerous areas.

Although this type of technology does substantially increase the ship's cost, it would give the Navy and Marines other resources for deployment..

Remove one half the height of its superstructure but lengthrn it to the #1 gun turret, in order to decrease topside weight, and center of gravity. Also, install the armor around around the superstructure as discussed above. That topside weight will balance out after the removal of the 3 gun turrets.

Remove the #2 and #3 turrets and all of their ammunition bunker machinery.

Install nuclear power systems in the #3 turret. Remove old traditional propulsion systems and replace with steam, cooling and gearing for a Nuclear plant.

Under the #2 turret install a multi directional Azipod (propeller) system.

If you took an anti ship missile and fired it at a WWII battleship, it would do superficial damage but not penetrate the armor protecting the bridge, the main battery gun turrets, the sides or deck covering the magazines and engine space. The armor protecting these areas was often as thick as the diameter of the guns, in hardened steel plates. So it struck head on would have to traverse 16 inches of steel, if struck at an oblique angle, even more.

Very possibly an antiship missile would simply bounce off the armor and explode harmlessly. If the missile had a lot of fuel left, it could start a surface fire with that fuel and its explosive charge,

WWII armor piercing shells were reduced explosion charge with delayed fuses and hardened cases and points to penetrate armor and explode within. A 16 inch shell was massive, a 2000 lb projectile and these are what the armor I described above is designed to protect against.

I suppose its possible to defeat armor with enough kinetic energy from a large antiship missile and shaped charges but the question is, what would they be used against? There are no more battleships.

The result of this conversion is a BBG that could sink any enemy surface action group protecting an enemy island or coastline, then strike antiaccess/area-denial targets such as antiship ballistic missiles, surface-to-air missile batteries, radars, air bases and and other enemy targets. Once it was safe enough to close within a hundred miles of the enemy coast, sixteen-inch guns with hypervelocity shells would come into play, destroying a half-dozen targets at a time with precision.

Could North Korea or Iran launch a nuclear-tipped missile to hit the US from a disguised container ship?

This is North Korea’s KN-18* MaRV ship killer missile. It has a maneuvering Hypersonic Glide vehicle with a 4 kiloton warhead and an accuracy of 7m CEP. Three of these were demonstrated on 26 August 2017.* [corrected missile name]

Their warhead reentry vehicle was obtained by cyber espionage from plans for the American Pershing -II missile and may have been copied by DPRK from the Chinese DF-21D missile after they obtained plans for the Pershing II.

Physical overpressure would likely kill the ship’s crew in the same way that a Thermobaric bomb does.

The KN-18 warhead has a radar seeker that can detect and identify the shapes of targets and terrain matching these with RCS templates stored in its memory. This means that it does not require active targeting updates.

It is very similar to the EMAD warhead seen on Iran’s missiles

China calls their version the WU-14

The point of the nuclear warhead is to create an over pressure that breaks the back of a ship.

Torpedoes are designed to do much the same by exploding under a ship’s keel, not actually hitting the ship.

In terms of intercept by an Aegis BMD vessel, this type of interceptor missile depends upon a radar operator predicting the Ballistic trajectory. If there is no ballistic trajectory interception by an Aegis missile becomes much more complicated.

This article below refers to the same missile incorrectly named as the KN-17 (designation subsequently revised by the Pentagon to KN-18):

the Soviet Union first developed a very primitive Anti Ship Ballistic Missile in 1962 known as the R-27K in Russia and as the SS-NX-13 in the west. This missile was abandoned due to SALT treaty negotiations, however it gave a lot of clues as to what a more modern Hypersonic Glide Vehicle could accomplish.

The R-27K used satellite targeting and then once launched homed in on the radar emissions from surface vessels. It was launched in a high lofted trajectory and could make targeting corrections of up to 30nm on re-entry. Against a target emanating radio-frequency transmissions, the SS-NX-13 was capable of a CEP of 0.1 to 0.2 nm.

The R-27K however did not have a hypersonic glide reentry vehicle. The chief advantage of a Hypersonic glide vehicle is to extend the range for engagement

(Chinese intelligence identified DPRK missile warhead yield in 2014. Accuracy of 7m CEP in August 26 tests was reported in Korean language news articles derived from ROK military intelligence disclosures)

In an all out war, nuclear tipped missles could render the Iowa class battleship defensible because of its thick armor, also, these can be used in a limited war.

To reinforce the protection of this BBG, in the future, it will be escorted by F-35B, a new type of task force, more advance than that of a typical carrier escorts of destroyers and cruisers.

see below....

- The 600-foot-long destroyer cruised along the Kennebec River to the Atlantic on its first voyage

- The ship, which weighs 15,000 tons, has taken four years to build at an estimated cost of $4.3 billion

The Navy destroyer is designed to look like a much smaller vessel on radar, and it lived up to its billing during recent builder trials.

LPD'S OR LHD'S MULTI ROLE COMBAT SHIP WILL REPLACE DESTROYERS ?

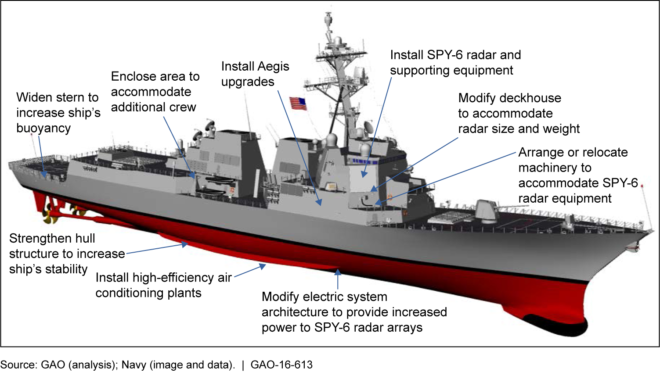

Navy DDG-51 Flight III modifications. SOURCE: GAO

The Navy has crammed as much electronics as it can into its new DDG-51 Flight III destroyers now beginning construction, Rear Adm. William Galinis said this morning. That drives the service towards a new Large Surface Combatant that can comfortably accommodate the same high-powered radars, as well as future weapons such as lasers, on either a modified DDG-51 hull or an entirely new design.

“It’s going to be more of an evolutionary approach as we migrate from the DDG-51 Flight IIIs to the Large Surface Combatant,” said Galinis, the Navy’s Program Executive Officer for Ships. (LSC evolved from the Future Surface Combatant concept and will serve along a new frigate and unmanned surface vessels). “(We) start with a DDG-51 flight III combat system and we build off of that, probably bringing in a new HME (Hull, Mechanical, & Engineering) infrastructure, a new power architecture, to support that system as it then evolves going forward.

AMPHIBIOUS TRANSPORT DOCK - LPD

Description

Amphibious transport dock ships are warships that embark, transport and land elements of a landing force for a variety of expeditionary warfare missions.

Features

LPDs are used to transport and land Marines, their equipment, and supplies by embarked Landing Craft Air Cushion (LCAC) or conventional landing craft and amphibious assault vehicles (AAV) augmented by helicopters or vertical take-off and landing aircraft (MV 22). These ships support amphibious assault, special operations, or expeditionary warfare missions and serve as secondary aviation platforms for amphibious operations.

Background

The LPD 17 San Antonio class is the functional replacement for over 41 ships including the LPD 4 Austin class, LSD 36 Anchorage class, LKA 113 Charleston class, and LST 1179 Newport class amphibious ships. The newly designated LPD Flight II ships (formerly LX(R)) will be the functional replacement for the LSD 41/49 Whidbey Island Class. The San Antonio class provides the Navy and Marine Corps with modern, sea-based platforms that are networked, survivable, and built to operate in the 21st century, with the MV-22 Osprey, the upgraded Amphibious Assault Vehicle, and future means by which Marines are delivered ashore.

Construction on USS San Antonio (LPD 17), the first ship of the class, commenced in June 2000 and was delivered to the Navy in July 2005. USS New York (LPD 21) was the first of three LPD 17class ships built in honor of the victims of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The ship's bow stem was cast using 7.5 tons of steel salvaged from the World Trade Center. The Navy named the eighth and ninth ships of the class Arlington and Somerset, in honor of the victims of the attacks on the Pentagon and United Flight 93, respectively. Materials from those sites were also incorporated into the construction of each ship. USS Portland (LPD 27), the eleventh ship of the class, delivered in 2017. LPDs 28 and 29 are currently under construction at Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) on the Gulf Coast. As the 12th and 13th San Antonio class ships, LPDs 28 and 29 will perform the same missions as the previous 11 ships of the class while incorporating technically feasible cost reduction initiatives and class lessons learned. In 2018 the Navy made the decision to transition to the LX(R) effort to a second flight of the LPD 17 design. LPD 30 will be the first of 13 planned LPD Flight II ships, for a total complement of 26 ships in the LPD 17 class.

General Characteristics, San Antonio Class LPD Flights I and II

Builder: Huntington Ingalls Industries

Propulsion: Four sequentially turbocharged marine Colt-Pielstick Diesels, two shafts, 41,600 shaft horsepower

Length: 684 feet

Beam: 105 feet

Displacement: Approximately 24,900 long tons (25,300 metric tons) full load

Draft: 23 feet

Speed: In excess of 22 knots (24.2 mph, 38.7 kph)

Crew: Ship's Company: 383 Sailors and 3 Marines. Embarked Landing Force: Flight I: 699 with surge capacity of 800; LPD 28/29:650; Flight II: 631.

Armament: Two Mk 46 30 mm Close in Guns, fore and aft; two Rolling Airframe Missile launchers, fore and aft: ten .50 caliber machine guns

Aircraft: Launch or land two CH-53E Super Stallion helicopters or two MV-22 Osprey tilt rotor aircraft or up to four AH-1Z or UH-1Y or MH-60 helicopters

Landing/Attack Craft: Two LCACs or one LCU; and 14 Amphibious Assault Vehicles

The DDG-51 is now the single most common type in the fleet, a vital part of the hoped-for 355-ship Navy, with some ships expected to serve into the 2070s:

- There are now 64 Arleigh Burkes of various sub-types in service;

- nine of the latest Flight IIA variant are in various stages of construction; and

- work is beginning on the new Flight IIIs in Mississippi (Huntington Ingalls Industries) and Maine (General Dynamics-owned Bath Iron Works).

The USS McCain (DDG 56)

The Navy is doubling down on long-standing programs to keep its older warships up to date and on par with the newest versions. But the current destroyers just won’t be able to keep up with the Flight III, which will have a slightly modified hull and higher-voltage electricity to accommodate Raytheon’s massive new Air & Missile Defense Radar. A stripped down version of the AMDR, the Enterprise Air Search Radar (EASR, also by Raytheon) is already going on amphibious ships and might just fit on older Burkes as well, however.

But it’s tight. On the Flight III, even with the hull modifications, “you kind of get to the naval architectural limits of the DDG-51 hullform,” Galinis told a Navy League breakfast this morning. “That’s going to bring a lot of incredible capabilities to the fleet but there’s also a fair amount of technical risk.”

So how different does the next ship need to be? “How much more combat capability can we squeeze into the current hullform?” Galinis said. “Do we use the DDG-51 hullform and maybe expand that? Do we build a new hullform?”

Lockheed Martin concept for their new HELIOS laser for the Navy.

“We’re looking at all the options, Sydney,” he said when reporters clustered around him after his talk. “(It’s in) very, very early stages… to say it’ll be one system over another or one power architecture over another, it’s way too early.”

“We’re still working through what that power architecture looks like,” Galinis told the breakfast. “Do we stay with a more traditional (gas-driven) system… or do we really make that transition to an integrated electric plant — and at some point, probably, bring in energy storage magazines…to support directed energy weapons and things like that?”

The admiral’s referring here to anti-missile lasers, railguns, and other high-tech but electricity-hungry systems. Having field-tested a rather jury-rigged 30 kilowatt laseron the converted amphibious ship Ponce, the Navy’s next step is a more permanent, properly integrated installation next year on an amphibious ship, LPD-27 Portland. (Subsequent LPDs won’t have the laser under current plans). But Portland is part of the relatively roomy LPD-17 San Antonio class, which has plenty of space, weight capacity, power, and cooling capacity (SWAP-C) available, in large part because the Navy never installed a planned 16 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes in the bow. By contrast, while the Navy’s studying how to fit a laser on the Arleigh Burkes, the space and electricity available are much tighter.

My proposed BBG's will have one half the height of the Superstructure or bridge but will have it extended all the way to the stern. Thus creating a flat top suitable for F -35B and helicopters.

THE US SHOULD USE AIRPOWER FIRST TO KNOCKOUT AII CHINESE, NORTH KOREAN AND RUSSIAN BASES WITH B-2 B=21, B-1, ARSENAL AIRSHIPS (RAPID DRAGONS) FOR AS LONG AS THERE ARE MILITARY ASSETS EXIST OF THE ENEMIES, WITHOUT THE USE OF SURFACE SHIPS. AIR SUPERIORITY FIRST BEFORE THE NAVY ACCORDING TO THE WAR GAMES BELOW.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/XNU7U35IBNCTRKEPNUR5HUH4S4.JPG)

I'm appreciate your writing skill. Please keep on working hard. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteWow this blog is awesome.

Wish to see this much more like this.

ReplyDeleteNice post, keep sharing such post.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteHello, nice to read your all blogs and learned a lot of new knowledge. Thank you!