| Origin of the Basques Since the Basque language is unrelated to Indo-European, it has long been thought that they represent the people or culture who occupied Europe before the spread of Indo-European languages there. A comprehensive analysis of Basque genetic patterns has shown that Basque genetic uniqueness predates the arrival of agriculture in the Iberian Peninsula, about 7,000 years ago. It is thought that Basques are a remnant of the early inhabitants of Western Europe, specifically those of the Franco-Cantabrian region. Basque tribes were already mentioned in Roman times by Strabo and Pliny, including the Vascones, the Aquitani, and others. There is enough evidence to support that at that time and later they spoke old varieties of the Basque language (see: Aquitanian language). In the Early Middle Ages (up to the 9th or 10th century) the territory between the Ebro and Garonne rivers was known as Vasconia, a blur cultural area and polity struggling to fend off the pressure of the Iberian Visigothic kingdom and Muslim rule on the south and the Frankish push on the north. A Basque presence is cited on the southern banks of the Loire river too (7th to 8th centuries). By the turn of the millennium, after Muslim invasions and Frankish expansion under Charlemagne, the territory of Vasconia (to become Gascony) fragmented into different feudal regions, for example, the viscountcies of Soule and Labourd out of former tribal systems and minor realms (County of Vasconia), while south of the Pyrenees the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom of Pamplona and the Pyrenean counties of Aragon, Sobrarbe, Ribagorza(later merged into the Kingdom of Aragon), and Pallars arose as the main regional powers with Basque population in the 9th century. The Kingdom of Pamplona (a central Basque realm), later known as Navarre, experienced feudalization and was subjected to the influences of its vaster Aragonese, Castilian and French neighbours. In the 11th and the 12th centuries, annexing key western territories Castile deprived Navarre of its ocean coast, confining it to its land borders. The Basque territory was ravaged by the War of the Bands, bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. After an undermining Navarrese civil war, the bulk of the realm would eventually fall confronted to the violence of Castilian troops, as the result of a series of wars between 1512 to 1524. The Navarrese territory north of the Pyrenees remained out of the rising Spanish rule. It would end up being formally incorporated into France in 1620. Nevertheless the Basques enjoyed a great deal of self-government until the French Revolution, that affected their Northern communities, and the civil wars named Carlist Wars, occurred in the Southern territories when they supported heir apparent Carlos and his descendants—to the cry of "God, Fatherland, King". In both North and South regions the Basques were defeated and their Charters abolished. Since then, despite the current limited self-governing status of the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre as settled by the Spanish Constitution, a significant part of Basque society is still attempting higher degrees of self-empowerment (see Basque nationalism), sometimes by acts of violence. Geography Political and administrative divisions Mountains of the Basque Country

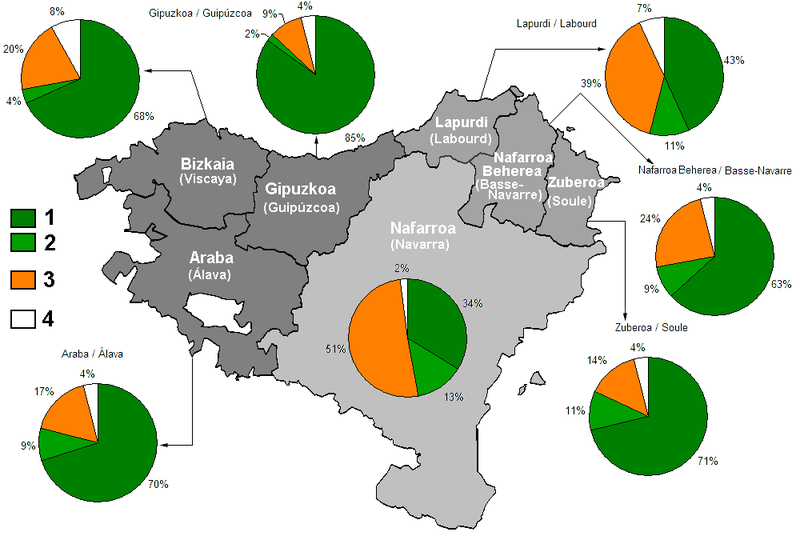

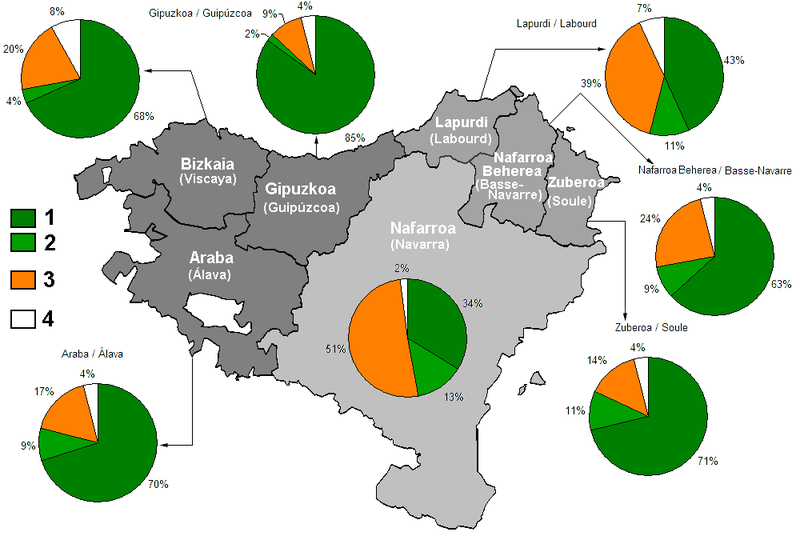

Leitza, in Navarre, Basque Country The Basque region is divided into at least three administrative units, namely the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre in Spain, and the arrondissement ofBayonne and the cantons of Mauléon-Licharre and Tardets-Sorholus in the département of Pyrénées Atlantiques, France. The autonomous community (a concept established in the Spanish Constitution of 1978) known as Euskal Autonomia Erkidegoa or EAE in Basque and as Comunidad Autónoma Vasca or CAV in Spanish (in English: Basque Autonomous Community or BAC), is made up of the three Spanish provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa. The corresponding Basque names of these territories are Araba, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, and their Spanish names are Álava, Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa. The BAC only includes three of the seven provinces of the currently called historical territories. It is sometimes referred to simply as "the Basque Country" (or Euskadi) by writers and public agencies only considering those three western provinces, but also on occasions merely as a convenient abbreviation when this does not lead to confusion in the context. Others reject this usage as inaccurate and are careful to specify the BAC (or an equivalent expression such as "the three provinces", up to 1978 referred to as "Provincias Vascongadas" in Spanish) when referring to this entity or region. Likewise, terms such as "the Basque Government" for "the government of the BAC" are commonly though not universally employed. In particular in common usage the French term Pays Basque ("Basque Country"), in the absence of further qualification, refers either to the whole Basque Country ("Euskal Herria" in Basque), or not infrequently to the northern (or "French") Basque Country specifically. Under Spain's present constitution, Navarre (Nafarroa in present-day Basque, Navarra historically in Spanish) constitutes a separate entity, called in present-day Basque Nafarroako Foru Erkidegoa, in Spanish Comunidad Foral de Navarra (the autonomous community of Navarre). The government of this autonomous community is the Government of Navarre. Note that in historical contexts Navarre may refer to a wider area, and that the present-day northern Basque province of Lower Navarre may also be referred to as (part of) Nafarroa, while the term "High Navarre" (Nafarroa Garaia in Basque, Alta Navarra in Spanish) is also encountered as a way of referring to the territory of the present-day autonomous community. There are three other historic provinces parts of the Basque Country: Labourd, Lower Navarre and Soule (Lapurdi, Nafarroa Beherea and Zuberoa in Basque; Labourd, Basse-Navarre and Soule in French), devoid of official status within France's present-day political and administrative territorial organization, and only minor political support to the Basque nationalists. A large number of regional and local nationalist and non-nationalist representatives has waged a campaign for years advocating for the creation of a separate Basque département, while these demands have gone unheard by the French administration. Population, main cities and languages Olentzero in Gipuzkoa, Basque Country Olentzero in Gipuzkoa, Basque Country There are 2,123,000 people living in the Basque Autonomous Community (279,000 in Alava, 1,160,000 in Biscay and 684,000 in Gipuzkoa). The most important cities in this region, which serve as the provinces' administrative centers, are Bilbao (in Biscay), San Sebastián (in Gipuzkoa) and Vitoria-Gasteiz (in Álava). The official languages are Basque and Spanish. Knowledge of Spanish is compulsory according to the Spanish Constitution (article no. 3), and knowledge and usage of Basque is a right according to the Statute of Autonomy (article no. 6), so only knowledge of Spanish is virtually universal. Knowledge of Basque, after declining for many years during Franco's dictatorship owing to official persecution, is again on the rise due to favourable official language policies and popular support. Currently about 33 percent of the BAC's population speaks Basque. Navarre has a population of 601,000; its administrative capital and main city, also regarded by many nationalist Basques as the Basques' historical capital, is Pamplona (Iruñea in modern Basque). Although Spanish and Basque are official languages in this autonomous community, Basque language rights are only recognised by current legislation and language policy in the province's northern region, where most Basque-speaking Navarrese are concentrated. Approximately a quarter of a million people live in the part of claimed French Basque Country. Basque-speakers refer to this as "Iparralde" ( Basque for North), and therefore to the Spanish provinces as "Hegoalde" (South). Much of this population lives in or near the Bayonne-Anglet-Biarritz (BAB) urban belt on the coast (in Basque these are Baiona, Angelu and Miarritze). The Basque language, which was traditionally spoken by most of the region's population outside the BAB urban zone, is today losing ground to French at a fast rate. Associated with the northern Basque Country's lack of self-government within the French state is the absence of official status for the Basque language throughout this region. The Basque diaspora

Basque festival in Buenos Aires, Argentina Large numbers of Basques have left the Basque Country for other parts of the world in different historical periods, often for economic or political reasons. Basques are often employed in sheepherding and ranching, maritime fisheries and merchants around the world. Millions of Basque descendants (see Basque American andBasque Canadian) live in North America (the United States and Mexico; Canada mainly in the provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec), Latin America (in all 23 countries), Southern Africa and Australia. Miguel de Unamuno said: "There are at least two things that clearly can be attributed to Basques: the Society of Jesus and the Republic of Chile. Louis Thayer Ojeda estimates that during the 17th and 18th centuries fully 45% of all immigrants in Chile were Basques. Over 3.5 million Basque descendants live in Chile and were a major influence in the country's cultural and economic development. A large wave of Basques emigrated to Latin America and substantial numbers settled elsewhere in North (the U.S.) and Latin America, particularly in Argentina,Paraguay, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Panama, Uruguay and Venezuela, where Basque place names are to be found, such as New Biscay, now Durango(Mexico), Biscayne Bay, Jalapa (Guatemala), Aguerreberry or Aguereberry Point in the United States, and the Nuevo Santander region of Mexico.[21] Nueva Vizcaya was the first province in the north of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico) to be explored and settled by the Spanish. It consisted mostly of the area which is today the states of Chihuahua and Durango. In Mexico most Basques are concentrated in the cities of Monterrey, Saltillo, Reynosa, Camargo, and the states of Jalisco, Durango, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Coahuila. The Basques were important in the mining industry, many were ranchers and vaqueros (cowboys), and the rest opened small shops in major cities like Mexico City, Guadalajara and Puebla. In Guatemala most Basques have been concentrated in Jalapa for six generations now, while some have immigrated to Guatemala City.

Basque festival in Winnemucca, Nevada The largest of several important Basque communities in the United States is in the area around Boise, Idaho, home to the Basque Museum and Cultural Center, host to a Basque festival every year, as well as a festival for the entire Basque diaspora every five years. Reno, Nevada, where the Center for Basque Studies and the Basque Studies Library are located in the University of Nevada, is another significant nucleus of Basque population. In Elko, Nevada there is an annual Basque festival that celebrates the dance, cuisine and cultures of the Basque peoples of Spanish, French and Mexican nationalities arrived to Nevada since the late 19th century. California has a major concentration of Basques in the United States, most notably in the San Joaquin Valley between Stockton, Fresno and Bakersfield. The city of Bakersfield itself has a large Basque community and the city boasts several Basque restaurants. There also exists a history of Basque culture in Chino, California. In Chino, there are two annual Basque festivals that celebrate the dance, cuisine, and culture of the peoples, and the surrounding area of San Bernardino County has many Basque descendants. They are mostly descendants of settlers from Spain and Mexico. These Basques in California are grouped in the human group known as Californios. Basques of European Spanish-French and Latin American nationalities also settled throughout the western U.S. in states like Louisiana, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah,Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Oregon, and Washington state. There are also many Basques and people of Basque ancestry living outside their homeland in Spain, France and other European countries. There are nearly 4.4 million who have some Basque surname in Spain. But of these only 19% reside in the Basque Country and the rest, more than 3.5 million Spanish with Basque surname, reside outside.  The origin of the Basques and the Basque language is a controversial topic that has given place to numerous hypotheses about their origin and so far none of them is conclusive or has been completely proven. A notorious fact is that the ancient language of the Basque people, the Basque language, which developed from the Proto-Basque language, is the only Pre-Indo-European language that is still extant in contemporary Europe. The current Basque language is a language isolate. The Basques have long been supposed to be a remnant of a pre-Indo-European population of Europe. However, this assumption has come under increasing criticism as genetic and linguistic studies have become more sophisticated. No firm conclusion has been reached on their origins. The origin of the Basques and the Basque language is a controversial topic that has given place to numerous hypotheses about their origin and so far none of them is conclusive or has been completely proven. A notorious fact is that the ancient language of the Basque people, the Basque language, which developed from the Proto-Basque language, is the only Pre-Indo-European language that is still extant in contemporary Europe. The current Basque language is a language isolate. The Basques have long been supposed to be a remnant of a pre-Indo-European population of Europe. However, this assumption has come under increasing criticism as genetic and linguistic studies have become more sophisticated. No firm conclusion has been reached on their origins.

The main hypothesis about the origin of the Basques are: -

The Native origin, according to which the Basque language would have developed over the millennia entirely between the north of the Iberian Peninsula and the current south of France, without the possibility of finding any kind of relationship between the Basque language and other modern languages in other regions. -

The Basque-Iberism, which theorizes the existence of a demonstrable close kinship between the Basque and the Iberian language, and therefore between their speakers. -

-

Theories of major acceptance Native origin This hypothesis states that, after the glaciations, the survivors of the Cro-Magnon in the European continent searched for warmer places, such as present-day Ukraine and the southwest of the continent, settling in the region of the Pyrenees and the south of France, due the mitigation of the cold due the Foehn effect. These settlements near the Pyrenees conformed the proto-Basque people.

Distribution of Paleolithic settlements in Europe. Starting in the year 16,000 BCE, the warmer climate allowed the expansion of proto-Basque groups, or proto-Europeans, across the entire continent and the north of Africa, and expanding the Magdalenian culture across Europe. This hypothesis is supported by three different research works, one of them genetic (based on the studies of Forster and Stephen Oppenheimer), the other two linguistic (the works of Theo Venneman) The Finnish linguist Kalevi Wiik proposed in 2008 that the current Basque language is the remainder of a group of "Basque languages" that were spoken in the Paleolithic in all western Europe. and that retreated with the progress of the Indo-European languages. According to Wiik, this theory coincides with the homogeneous distribution of the Haplogroup R1b in Atlantic Europe. Paleogenetic investigations The geneticist Spencer Wells, director of the Genographic Project of the National Geographic Society has pointed out that, genetically, the Basques are indistinguishable of the rest of Iberians, a fact that has been later confirmed by a study led by Jaume Bentranpetit, at the Pompeu Fabra University, inBarcelona. Paleogenetic investigations by the Complutense University of Madrid indicate that the Basque people have a genetic profile coincident with the rest of the European population and that goes back to Prehistoric times. The haplotype of the mitochondrial DNA known as U5 entered in Europe during the Upper Paleolithic and developed varieties as the U8a, native of the Basque Country, which is considered to be Prehistoric, and as the J group, which is also frequent in the Basque population. On the other side, the haplotype V, which is also present in the Sami people, has also been found in some Basque populations and comes from Prehistoric European populations. The works of Alzualde A, Izagirre N, Alonso S, Alonso A, de la Rua C. about mitochondrial DNA of the Human remains found in the Prehistoric graveyard of Alaieta, in Alava, note that there are no differences between these remains and others found across Atlantic Europe. The works of Peter Forster make him presume that 20.000 years ago the Humans sheltered in Beringia and Iberia, staying in the latter one the haplotypes H and V. The people from Iberia and the south of France would have then repopulated (c. 15.000 years ago) parts of Scandinavia and the north of Africa. Studies based on the Y chromosome genetically relate the Basques with the Celtic Welsh and Irish;[16] Stephen Oppenheimer from the University of Oxford says that the current inhabitants of the British Isleshave their origin in the Basque refuge during the last Ice age. Oppenheimer reached this conclusion through the study of correspondences in the frequencies of genetic markers between various European regions. Other genetic studies have found differences among the inhabitants that currently inhabit the Basque territories. Some works, including those by René Herrera of the University of Florida and Mikel Iriondo, Carmen Manzano and María del Carmen Barbero from the University of the Basque Country, even point to the existence of different types within the Basque people. René Herrera says: It is believed that they [the Basques] descend directly from the Cro-Magnon, representing their last refuge during the ice age and with a very particular DNA. Basically, the study tells us that each province and each region has its own genetic profile which is different between them. We can speak of areas traditionally Basques and some other that have been permeated with Peninsular migrations. Most of those differences can be attributed to foreign migrations from other parts of Europe or Iberia, but some others cannot. That is because even in regions with profiles genetically mainly Basque, exist differences. In any case, the haplogroup R1b, which originated during the last ice age at least 18.500 years ago, when Human groups settled in the south of Europe and that is currently common in the European population, can be found most frequently in the Basque Country (91%), Wales (89%) and Ireland (81%). The current population of the R1b from western Europe would probably come from a climatic refuge in theIberian Peninsula, where the haplogroup R1b1c (R1b1b2 or R1b3) originated. During the Allerød oscillation, circa 12.000 years ago, descendants of this population would have repopulated Western Europe.[17]The rare variety R1b1c4 (R1b1b2a2c) has almost always been found among the Basque people, both in the Northern and Southern Basque Country. The variety R1b1c6 (R1b1b2a2d) registers a high incidence in the Basque population, 19%. In the linguistics area there are two lines of investigation, both based on etymology; one on toponyms, not only in the Basque Country but also in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula and Europe, and the other on the proper etymology of the Basque words. The aizkora controversy On the surface, Basque appears to have several terms connected to implements containing a root which resembles the word (h)aitz "stone": -

(h)aizkora "axe" -

(h)aitzur "hoe" -

(h)aitzur "shears" -

(h)aiztur "tongs" -

aizto "knife" Theories regarding the possibility of such a share root were put forward variously by Lucien Bonaparte, Unamuno, Baroja and others, suggesting a terminological continuity since the stone age.[23] Today, these theories are viewed with suspicion as aizkora has been identified as a loan from Latin asciola and the fact that historically the root of the remaining terms was ainz- (based on the Roncalese dialect of Basquewhich is known for its preservation of historical nasals and has the documented forms antzur, ainzter, aintzur and ainzto) and thus a reconstructed root *ani(t)z or *ane(t)z, whereas there are no traces of such a nasal in the word haitz "rock" (cf Roncalese aitz)

Sides of an Iberian coin with the inscription Baskunes. The theory of the Basque-Iberism affirms that, somehow, there is a direct relation between the Basque language and the Iberian language, in a way that the Basque would be the result of an evolution of the Iberian language, or that the Basque belonged to the same language family. The first one to point out this theory was Strabo in the 1st century BC (that means, when the Iberian language was still spoken); he asserted that the Iberians and the Aquitanians were similar physically and that spoke similar languages. The German Wilhelm von Humboldt exposed, in the early 19th Century, a thesis in which he stated that the Basque people were Iberians, following some studies he conducted. Caucasian origin Some researchers have propounded the similarities between the Basque language and the Caucasan languages, especially the Georgian language, with the argumentation that a group of Caucasian people may have united to the invasion of Europe with the Indo-European people. From a grammatical or typologic point, they share agglutinative, ergative-absolutive languages, with the same system of declension. According to the Caucasian researcher Jan Braun, the Proto-Basque language and the Proto-Kartvelian language separated circa the 4th millennium BC and in the following 5500 years they developed separately. The comparison between the matrilineality and patrilineality lineages of the native peoples from the Basque Country and Georgia has allowed to find significant differences. The hypothesis that related both populations is only based on the typological similarities, which is never a good marker of linguistic kinship. These superficial similarities in the linguistic typologies do not seem to come accompanied of a genetic relation at a population level. However, the possible relation between the Basque and the languages of the Caucasus is denied by authors such as Larry Trask, who stated that the comparisons were wrongly made, given the fact that the Basque language was compared with several Caucasian languages at the same time. Paradoxically, despite not having found linguistic relations, the genetic haplogroup R1b3 has been found between the Bashkirs of Volga.These theories are based on the Old European hydronymy, assuming that the first inhabitants of Europe spoke a common tongue or languages of the same language family. This theory is not accepted by most linguistics, who believe that in a territory as big as Europe more than one language had to be spoken. In January, 2003, the Spanish edition of the scientific magazine Scientific American published an study conducted by Theo Vennemann, professor of theoretical linguistics of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where he concluded: Much of the names of settlements, rivers, mountains, valleys and landscapes in Europe would have their origin in Pre-Indo-European languages, specifically the Basque language. Vennemann: We do not fall in exaggeration if we say that all the Europeans are Basques. According to Vennemann, the Proto-Basque language (or a language family from which the Basque language originated) was the linguistic stratum in which later the Indo-European languages settled. He found, among other examples, the Basque words "ibai" (river) and "ibar" (bottom) to repeat continuously in European rivers, or the word "haran" (valley) in toponyms such as Val d'Aran, Arendal, Arundel, Arnach,Arnsberg, Aresburg, Ahrensburg, Aranbach or Arnstein. The Vennemann theory has been criticized by Basque scholars and it is not accepted by most of the linguistics. Specifically, Trask, after many punctual critics to the methods used, affirmed that Vennemann had found an agglutinative language, but with no relation to the Basque language, and that probably it is simply the Indo-European language, as many other linguistic scholars agree. Joseba Andoni Lakarra, researcher of the Proto-Basque language criticizes the thesis of Vennemann, saying, as Trask, that he identifies modern Basque roots that are not related to the archaic Basque. In the same way, Lakarra says that despite the Basque being now an agglutinative language, there are reasons to believe that previously it was not so. Roman records Basque and other pre-Indo-European tribes (in red) at the time of Roman arrival The early story of the Basque people was recorded by Roman classical writers, historians and geographers, as Pliny the Elder, Strabo andPomponius Mela. The present-day Basque Country was, by the time of the Roman arrival in the Iberian Peninsula, inhabited by Aquitanianand Celtic tribes. The Aquitanians are also known as the "Proto-Basque people", and included several tribes as the Vascones, were located at both sides of the western Pyrenees. In present-day Biscay, Gipuzkoa and Álava were located the Caristii, Varduli and Autrigones, whose origin is still not clear. It is not known if these tribes were of Aquitanian origin, related to the Vascones, of if they were of Celticorigin. The latter seems more likely, based on the use of Celtic and Proto-Celtic toponyms by these tribes, and not a single Basque toponym. These tribes would have then suffered a Basquisation caused by progress of the Aquitanian tribes on their territory. Strabo in the 1st century AD reported that the Ouaskonous (Vascones) inhabited the area around the town of Pompelo, and the coastal town of Oiasona in Hispania. He also mentioned other tribes between them and the Cantabrians: the Varduli, Caristii, and Autrigones.About a century later Ptolemy also listed the coastal Oeasso beside the Pyrénées to the Vascones, together with 15 inland towns, including Pompelon. Pompelo/Pompelon is easily identified as modern-day Pamplona, Navarre. The border port of Irún, where a Roman harbour and other remains have been uncovered, is the accepted identification of the coastal town mentioned by Strabo and Ptolemy. Three inscriptions in an early form of Basque found in eastern Navarre can be associated with the Vascones. However, the Vascones appear to have been just one tribe within a wider language community. Across the border in what is now France the Aquitani tribes of Gascony spoke a language different from the Celts and were more like the Iberi. Although no complete inscription in their language survives, a number of personal names were recorded in Latin inscriptions, which attest to Aquitanian being the precursor of modern Basque (This extinct Aquitanian language should not be confused with Occitan, a Romance language spoken in Aquitaine since the beginning of the Middle Ages). | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment